In an article found at the ligonier website, Dr. R. C. Sproul writes:

In an article found at the ligonier website, Dr. R. C. Sproul writes:

In the seventeenth chapter of his gospel, the Apostle John recounts the most extensive prayer that is recorded in the New Testament. It is a prayer of intercession by Jesus for His disciples and for all who would believe through their testimony. Consequently, this prayer is called Jesus’ High Priestly Prayer. Christ implored the Father in this prayer that His people might be one. He went so far as to ask the Father that “they may be one even as we are one” (v. 22b). He desired that the unity of the people of God — the unity of the church — would reflect and mirror the unity that exists between the Father and the Son.

Early in church history, as the church fathers were hammering out the cardinal doctrines of the faith, they wrestled with the nature of the church. In the fourth century, in the Nicene Creed, the church was defined with four adjectival qualifiers: one, holy, catholic, and Apostolic. These early saints believed, as Scripture teaches, that the church is one, a unity.

We know that the prayers of Christ, our High Priest, are efficacious and powerful. We know that the early church experienced remarkable unity (Acts 2:42–47; 4:32). Yet the church today, in its visible manifestation, is probably more fragmented and fractured than at any time in church history. There are thousands of denominations in the United States and even more around the world. How, then, are we to understand Christ’s prayer for the unity of the church? How are we to understand the ancient church’s declaration that the church is one?

There have been different approaches to this. In the twentieth century, we witnessed the rise of relativistic pluralism, a philosophy that allows for a wide diversity of theological viewpoints and doctrines within a single body. In the face of numerous doctrinal disputes, some churches have tried to maintain unity by accommodating many differing views. Such pluralism has frequently succeeded in maintaining unity — at least organizational and structural unity.

However, there’s always a price tag for pluralism, and historically, the price tag has been the confessional purity of the church. In the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, when the Protestant movement began, various ecclesiastical groups created confessions, creedal statements that set forth the doctrines these groups embraced. In the main, these documents reiterated that body of doctrine that had been passed down through the centuries, having been defined in the so-called ecumenical councils of the first several centuries. These confessions also spelled out the particular beliefs of these various groups. For centuries, Protestantism was defined confessionally. But in our day, the older confessions have been largely relativized as churches try to broaden their confessional stances in order to achieve a visible unity.

There has always been a certain level of pluralism within historic Christianity. The church has always made a distinction between heresy and error. It is a distinction not of kind but of degree. The church is always plagued with errors, or at least members who are in error in their thinking and beliefs. But when an error becomes so serious that it threatens the very life of the church, when it begins to approach a doctrinal mistake that affects the essentials of the Christian faith, the church has had to stand up and say: “This is not what we believe. This false belief is heresy and cannot be tolerated within this church.” Simply put, the church has recognized that it can live with differences that are not of the essence of the church, matters that are not essentials of the faith. But other matters are far more serious, striking at the very basics of the faith. So, we make a distinction between those errors that impact the being of the church — major heresies — and lesser errors that impact the well-being of the church.

Today, however, the church, in order to achieve unity, increasingly negotiates central truths, such as the deity of Christ and the substitutionary atonement. This must not be allowed to happen, for the Bible calls us to “the unity of the faith” (Eph. 4:13), a unity based on the truth of God’s Word. Believers who are trying to be faithful to the Scriptures know that the New Testament writers stress the need for us to guard the truth of the faith once delivered (Jude 3; 1 Tim. 6:20a) as well as the need for us to beware those who would undermine the truth of the Apostolic faith by means of false doctrine (Matt. 7:15).

The Christian faith is lived on the razor’s edge. The Apostle Paul says, “If possible, so far as it depends on you, live peaceably with all” (Rom. 12:18). We need to bend over backward to keep peace and maintain unity. Yet, at the same time, we are called to be faithful to the truth of the gospel and to maintain the purity of the church. That purity must never be sacrificed to safeguard unity, for such unity is no unity at all.

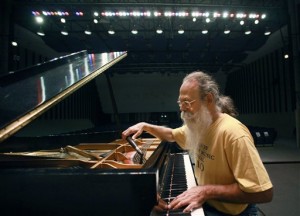

“Has it ever occurred to you that one hundred pianos all tuned to the same fork are automatically tuned to each other? They are of one accord by being tuned, not to each other, but to another standard to which each one must individually bow.

“Has it ever occurred to you that one hundred pianos all tuned to the same fork are automatically tuned to each other? They are of one accord by being tuned, not to each other, but to another standard to which each one must individually bow.