Sinclair Ferguson:

Category Archives: Inerrancy

Jesus’ View of Scripture

The Meaning Of Sola Scriptura

Does the Bible Contain Errors?

This excerpt is adapted from R.C. Sproul’s foreword in The Inerrant Word: Biblical, Historical, Theological, and Pastoral Perspectives by John MacArthur

“The Bible is the Word of God, which errs.” From the advent of neoorthodox theology in the early twentieth century, this assertion has become a mantra among those who want to have a high view of Scripture while avoiding the academic liability of asserting biblical infallibility and inerrancy. But this statement represents the classic case of having one’s cake and eating it too. It is the quintessential oxymoron.

Let us look again at this untenable theological formula. If we eliminate the first part, “The Bible is,” we get “The Word of God, which errs.” If we parse it further and scratch out “the Word of” and “which,” we reach the bottom line:

“God errs.”

The idea that God errs in any way, in any place, or in any endeavor is repugnant to the mind as well as the soul. Here, biblical criticism reaches the nadir of biblical vandalism.

How could any sentient creature conceive of a formula that speaks of the Word of God as errant? It would seem obvious that if a book is the Word of God, it does not (indeed, cannot) err. If it errs, then it is not (indeed, cannot be) the Word of God.

To attribute to God any errancy or fallibility is dialectical theology with a vengeance.

Perhaps we can resolve the antinomy by saying that the Bible originates with God’s divine revelation, which carries the mark of his infallible truth, but this revelation is mediated through human authors, who, by virtue of their humanity, taint and corrupt that original revelation by their penchant for error. Errare humanum est (“To err is human”), cried Karl Barth, insisting that by denying error, one is left with a docetic Bible—a Bible that merely “seems” to be human, but is in reality only a product of a phantom humanity.

Who would argue against the human proclivity for error? Indeed, that proclivity is the reason for the biblical concepts of inspiration and divine superintendence of Scripture. Classic orthodox theology has always maintained that the Holy Spirit overcomes human error in producing the biblical text.

Barth said the Bible is the “Word” (verbum) of God, but not the “words” (verba) of God. With this act of theological gymnastics, he hoped to solve the unsolvable dilemma of calling the Bible the Word of God, which errs. If the Bible is errant, then it is a book of human reflection on divine revelation—just another human volume of theology. It may have deep theological insight, but it is not the Word of God.

Critics of inerrancy argue that the doctrine is an invention of seventeenth-century Protestant scholasticism, where reason trumped revelation—which would mean it was not the doctrine of the magisterial Reformers. For example, they note that Martin Luther never used the term inerrancy. That’s correct. What he said was that the Scriptures never err. Neither did John Calvin use the term. He said that the Bible should be received as if we heard its words audibly from the mouth of God. The Reformers, though, not using the term inerrancy, clearly articulated the concept.

Irenaeus lived long before the seventeenth century, as did Augustine, Paul the apostle, and Jesus. These all, among others, clearly taught the absolute truthfulness of Scripture.

The church’s defense of inerrancy rests upon the church’s confidence in the view of Scripture held and taught by Jesus himself. We wish to have a view of Scripture that is neither higher nor lower than his view.

The full trustworthiness of sacred Scripture must be defended in every generation, against every criticism.

When Biblical Inerrancy Is No Longer Embraced

This question and answer (involving Dr. William Lane Craig) shows the very dire consequences that can occur when the doctrine of biblical inerrancy is abandoned… it is a very troubling downward slide.

Does Inerrancy Matter?

Does Inerrancy Matter? The Legacy of James Montgomery Boice

Does Inerrancy Matter? The Legacy of James Montgomery Boice

by Dr. Derek Thomas (original source here)

“[I]f part of the Bible is true and part is not, who is to tell us what the true parts are? There are only two answers to that question. Either we must make the decision ourselves, in which case the truth becomes subjective. The thing that is true becomes merely what appeals to me. Or else, it is the scholar who tells us what we can believe and what we cannot believe… God has not left us either to our own whims or to the whims of scholars. He has given us a reliable book that we can read and understand ourselves.”

These words, arguing the logic of an inerrant Scripture, were part of a sermon preached on May 23, 1993 by James Montgomery Boice (see, Whatever Happened to the Gospel of Grace [Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2009], 69). The sermon was preached on the twenty-fifth anniversary of his pastorate at Tenth Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia. Boice began by drawing attention to the fact that the doctrine of Scripture had been the most important thing that Tenth Presbyterian Church had stood for in its (then) one hundred sixty-four year existence.

At the close of 1977, ten years into his pastorate at Tenth, Dr. Boice helped in the foundation of the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy, and subsequently chaired it. A few years later, Boice published, Standing on the Rock: Upholding Biblical Authority in a Secular Age (Grand Rapids, MI: Kregel, 1984) in which he answered the question, why does inerrancy matter? He noted that most of his contemporaries seemed more preoccupied with having a “personal relationship” with Jesus than addressing the doctrine of Scripture. But who is this Jesus with whom we are to have a personal relationship if not the Jesus accurately (inerrantly) portrayed in Scripture? We live a relativistic age, Boice argued, where there is no such thing as truth, only “what’s true for me.” “When people operate on that basis, they usually think they have found freedom because, in not being tied to absolutes, they have freedom to do anything they wish. They are not tied to God or to a God-given morality. They do not have to acknowledge any authority. But the consequence of this kind of freedom is that they are cast adrift on the sea of meaningless existence.” (Standing on the Rock [1994 edition], 17).

Absolute truth

Inerrancy is important, Boice argued, in a postmodern culture, to provide the individual with a basis for absolute authority in doctrine and morals. Without absolutism, we are adrift in a sea of relativism and subjectivism. Without a trustworthy Scripture, there is only a mere potentiality of meaning actualized differently in differing circumstances. We are trapped in the present, our own historical circumstances, and cannot understand the past or have any certainty of the future. Truth lies in community and the voice of the Spirit – all subjective entities – wisps that appear for a moment promising much and delivering little.

Ultimately, as Boice argued all too well, if there is no ultimate meaning, nothing I say makes any sense, including the words “there are no absolutes”! What Boice saw was that without inerrancy, the relevance of Christianity diminishes. Why should anyone commit their lives to the institution of the church if there is no certainty that what she stands for is true. Relativism as to truth leads to relativism as to behavior and commitment. The moral drift of the last thirty years with its accompanying.

Authoritative Preaching

What is preaching? It is either Truth delivered through personality (as Philips Brooks suggested), or it is the opinion of men (and women). The steps from the original autographs to text, translation and meaning is a complex one, involving a commitment to providence as well as a rigorous hermeneutic (and hence, the Council of Biblical Inerrancy also issued a statement, “Formal Rules of Biblical Interpretation”). “It is only when ministers of the gospel hold to this high view of Scripture that they can preach with authority and effectively call sinful men and women to full faith in Christ.” (Standing on the Rock, 24). Continue reading

Defining Our Terms: The Doctrine of Scripture

In an article at ligonier.org entitled “The Doctrine of Scripture: Defining Our Terms” Kevin Gardner “The Bible says it. I believe it. That settles it.” If you don’t grasp what the Bible is and how it came to be, you’ll never fully grasp its meaning. Since the meaning of the Bible is vitally important to our faith and life, we will here briefly define a few key terms that relate to the doctrine of Scripture as the study of God’s Word written.

In an article at ligonier.org entitled “The Doctrine of Scripture: Defining Our Terms” Kevin Gardner “The Bible says it. I believe it. That settles it.” If you don’t grasp what the Bible is and how it came to be, you’ll never fully grasp its meaning. Since the meaning of the Bible is vitally important to our faith and life, we will here briefly define a few key terms that relate to the doctrine of Scripture as the study of God’s Word written.

Authority: The power the Bible possesses, having been issued from God, for which it “ought to be believed and obeyed” (Westminster Confession 1:4). Because of its divine author, the Bible is “the source and norm for such elements as belief, conduct, and the experience of God” (Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms).

Autographs: The original texts of the biblical books as they issued from the hands of the human authors.

Canon: The authoritative list of inspired biblical books. Within a short time after Jesus’ death, the New Testament canon was affirmed by evaluating the Apostolicity, reception, and teachings of books, but ultimately, the canon is self-authenticating, as the voice of Christ is heard in it (John 10:27; WCF 1:5).

Inerrancy: The position that the Bible affirms no falsehood of any sort; that is, “it is without fault or error in all that it teaches,” in matters of history and science as well as faith (Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy). Inerrancy allows for literary devices, such as metaphors, hyperbole, round numbers, and colloquial expressions.

Infallibility: The position that the Bible cannot err or make mistakes, and that it “is completely trustworthy as a guide to salvation and the life of faith and will not fail to accomplish its purpose” (Westminster Dictionary). As the Christian church has traditionally taught, this doctrine is based on the perfection of the divine author, who cannot speak error.

Inspiration: The process by which God worked through the human authors of the Bible to communicate His revelation. The term derives from the Greek theopneustos, meaning “God-breathed” (2 Tim. 3:16), and refers to God as the ultimate source of the Scriptures.

Organic inspiration: The process by which God guided the human authors of Scripture, working in and through their particular styles and life experiences, so that what they produced was exactly what He wanted them to produce. The text is truly the work of the human authors—God did not typically dictate to them as to a stenographer—and yet the Lord stands behind it as the ultimate source.

Necessity: Refers to mankind’s need for God’s special revelation in the Scriptures in order to obtain knowledge of the gospel and the plan of salvation, which cannot be learned through the general revelation of nature and conscience.

Perspicuity: The clarity of the Bible; that is, that which is necessary to know and believe regarding life and salvation is “so clearly propounded, and opened in some place of Scripture or the other,” that anyone may understand them (WCF 1:7).

Scripture: From the Latin scriptura, meaning “writings”; refers to sacred texts, but more specifically, the Bible as the Word of God written.

Special revelation: The things that God makes known about Himself apart from nature and conscience (general revelation; cf. Rom. 1:19–21). These things, having to do with Christ and the plan of salvation, are found only in the Bible.

Sufficiency: All that is needed to know and believe regarding salvation and what pleases God is found in the Bible.

Verbal, plenary inspiration: The extending of God’s superintendence of the writing of Scripture down to the very choice of words, not merely to overarching themes or concepts; that is, “the whole of Scripture and all of its parts, down to the very words of the original,” were inspired (Chicago Statement).

Inerrancy Defended

Robert M. Bowman Jr. (born 1957) is an American Evangelical Christian theologian specializing in the study of apologetics. In an article (here) he writes:

Kyle Roberts, a theologian at United Theological Seminary and a former evangelical, has written a blog article on Patheos entitled “Seven Problems with Inerrancy.” Roberts is an example of a growing number of theologians who argue that we should retain faith in Jesus Christ and even confess Scripture to be “inspired” or “the Word of God” while rejecting the belief that Scripture is inerrant. In this response, I will point out seven problems with Roberts’s position.

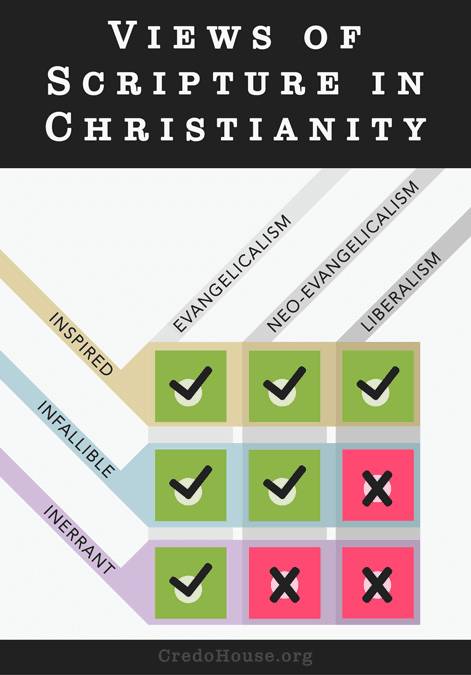

View of Scripture in Christianity – Inspiration, Inerrancy, Infallibility

View of Scripture in Christianity – Inspiration, Inerrancy, Infallibility

Note that I will not be arguing for the existence of God, the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, or even the status of the books of the Bible as Scripture in this article. I am addressing the views of people who affirm these things but deny the inerrancy of Scripture. My contention is that those who affirm those basic elements of Christianity are being inconsistent if they do not also accept the inerrancy of Scripture. I offer seven reasons in support of this conclusion.

1. Jesus Christ believed that Scripture is inerrant.

In an essay of over 1,700 words, Roberts offers various criticisms—actually far more than seven—of belief in the inerrancy of Scripture, yet he never addresses or even mentions the question of what Jesus Christ thought on the matter. This omission is quite common among Christian critics of inerrancy.

These critics often insist that Christ, not Scripture, is the central focus of Christian faith. Roberts, for example, asserts that “the Bible creates an occasion for us to narratively engage the story of Jesus–but it is the living Jesus that is the goal.”

Fair enough. Evangelicals certainly affirm that Jesus is the central focus and subject of Scripture, including the Old Testament, and that its goal is to lead us to faith in Jesus, as Jesus himself taught (Luke 24:27, 44-47; John 5:39-40). However, if we are serious about following Jesus Christ, we must accept his view of Scripture.

Just as evangelicals accept Christ’s claim that all of the Scripture is centered on him, they also accept Christ’s view that Scripture is the unerring Word of God.[1]

To learn how Jesus viewed Scripture, we must consult the most reliable sources of historical information about Jesus’ teachings and actions—the Gospels in the New Testament. A progressive or liberal Christian who believes that Jesus died on the cross and rose from the grave as reported in the canonical Gospels presumably would be willing to consult the Gospels at least as valuable sources of information about what Jesus said and did. When we do this, we discover that Jesus clearly accepted the conventional Jewish belief, taught especially by the Pharisees, that Scripture is unerring revelation from God.

Near the beginning of the Sermon on the Mount—which progressive and liberal Christians often assert epitomizes what it means to follow Jesus—we find that Jesus said the following:

“Do not think that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I did not come to abolish but to fulfill. For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass from the Law until all is accomplished” (Matt. 5:17-18).

That is a clear articulation of the traditional ancient Jewish view of Scripture as verbally inspired by God. The rest of the Gospels consistently attest that Jesus held this view.

Thus, that Jesus held to the inerrancy of Scripture is as certain as any fact about his teaching. If we were to reject the Gospels’ testimony as to Jesus’ view of Scripture, we would have no basis for knowing anything about Jesus’ teaching. An atheist or agnostic might be able to accept this conclusion, but it makes no sense for progressive Christians, most of whom speak very highly in particular of the Sermon on the Mount, to reject what the Gospels report concerning Jesus’ view of Scripture.

2. Christian non-inerrantists ignore or distort nearly two millennia of Christian affirmations of the absolute truth of Scripture.

Critics of inerrancy commonly allege that it is supposedly of recent vintage in the history of Christianity. We are often told that inerrancy is a distinctively modern theory of the nature of Scripture driven by Enlightenment rationalism. For example, the fifth objection that Roberts gives to inerrancy is that it “is simply too modernistic and ‘objectivist’ in orientation.” If that were true, it would be grounds for at least questioning the idea of inerrancy. However, it’s simply not true. Consider what just three of the greatest figures in church history said on the subject:

It is to the canonical Scriptures alone that I am bound to yield such implicit subjection as to follow their teaching, without admitting the slightest suspicion that in them any mistake or any statement intended to mislead could find a place.

Augustine of Hippo: “It is to the canonical Scriptures alone that I am bound to yield such implicit subjection as to follow their teaching, without admitting the slightest suspicion that in them any mistake or any statement intended to mislead could find a place” (Letters 82.3).

Thomas Aquinas: “Only to those books or writings which are called canonical have I learnt to pay such honour that I firmly believe that none of their authors have erred in composing them” (Summa theologiae 1a.1.8).

Martin Luther: “Everyone knows that at times they have [the early church fathers] erred as men will; therefore, I am ready to trust them only when they prove their opinions from Scripture, which has never erred” (Weimarer Ausgabe, 7:315). Continue reading

The Inspiration, Inerrancy and Preservation of Scripture

Starting with a flawed foundation dooms a building, the Spirit overcomes our ignorance and our traditions, all to His glory, but we should surely be very concerned that we give new believers a solid foundation upon which to develop a heart of wisdom to God’s glory.

One of the areas I have focused upon in my ministry that is vital to the maturity of modern Christians is the trustworthiness of the Scriptures. I am convinced that we must tackle the “tough issues” in the context of the community of faith before people are exposed to the “spin” of the enemies of the faith as they cherry-pick the facts of history and prey upon the unwary and immature.

One of the most often asked questions I encounter has to do with the relationship between the reality of textual variation and the doctrine of inerrancy, or even the general concept of inspiration. And this goes directly to the foundation that must be laid regarding this vital area.

First, we must understand that the doctrine of inspiration speaks to the origination and character of the original writings themselves, their character and authority. Inerrancy speaks to the trustworthiness of the supernatural process of inspiration, both with reference to the individual texts (Malachi’s prophecy, 2 John) as well as the completed canon (matters of pan-canonical consistency, the great themes of Scripture interwoven throughout the Old and New Testaments). While related to the issue of transmission, they are first and foremost theological statements regarding the nature of Scripture itself. They were true when Scripture was written, hence, in their most basic forms, are not related to the transmissional process.

Many new believers, upon reading the high view of Scripture found in the Bible itself, or hearing others speak of its authority and perfection, assume this means that the Bible floated down out of heaven on a cloud, bound together as a single leather-bound volume, replete with gold page edging and thumb indexing. The fact that God chose to reveal Himself in a significantly less “neat” fashion, one that was very much involved in the living out of the life of the people of God, can be disturbing to people. They want the Bible to be an owner’s manual, a never-changing PDF file that is encrypted and locked against all editing. And while I surely believe God has preserved His Word, the means by which He has done so is fully consistent with the manner of the revelation itself. We dare not apply modern standards derived from computer transfer protocols and digital recording algorithms to the ancient context for one simple reason: by doing so we are precluding God’s revelation and activity until the past few generations! What arrogance on our part! We must allow God to reveal Himself as He sees fit, when He sees fit, and we must derive our understanding of His means of safeguarding His revelation from the reality of the historical situation, not our modern hubris. Continue reading

Scripture’s Authority, Sufficiency and Finality

In an article entitled “The Authority, Finality of Scripture” originally published in The Banner of Truth magazine August-September 2014, Dr. Sinclair Ferguson writes:

In an article entitled “The Authority, Finality of Scripture” originally published in The Banner of Truth magazine August-September 2014, Dr. Sinclair Ferguson writes:

If God has given us the Scriptures to be the canon or rule for our lives, it follows that we must regard them as the supreme authority for our lives. Paul tells us that they are ‘breathed out’ by God. There can be no more authoritative word than one that comes to us on divine breath.

The Scriptures are also a sufficient authority for the whole of the Christian life. They are ‘profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness, that the man of God may be competent, equipped for every good work’ (2 Tim. 3:16).

The Scriptures do not tell us everything about everything. They provide no instruction about computer programming, or how best to organise a library, the correct way to swing a golf club, or how to play chess. They do not tell us how far away the sun is from the earth, what DNA is, how best to remove an appendix surgically, the best coffee to drink, or the name of the person we should marry.

That is not an expression of any deficiency on their part. For there is a focus and a goal to the sufficiency of the Scriptures. Everything I need to learn in order to live to the glory of God and enjoy him forever I will find in the application of Scripture.

Yet this narrow focus broadens out into everything. For one thing, Scripture teaches us something about everything. Since the Bible gives us grounds for believing we live in a universe, Christians understand that everything has the characteristic of createdness, of derivativeness, and also that everything fits into the grand design of God.

So Scripture is sufficient to give me a rational ground for thinking about anything and everything on the assumption that this world and everything in it make sense. Further, no matter what my calling or abilities, the Scriptures are sufficient to teach me principles that will enable me to think and act in a God-honouring way when I am engaged in any activity or vocation.

Inerrancy

In this context it is appropriate for us to ask an important and much debated question: If Scripture is our final authority, exactly how reliable is it as the authority on which we should base the whole of our lives?

If, convinced that the Bible is the word of God, we ask that question from a theological point of view there seems to be only one reasonable answer: Scripture is completely reliable. For the God who has ‘breathed out’ Scripture is trustworthy in everything he does and says. He is the God who cannot lie (Titus 1:2; Heb. 6:18; cf. Num. 23:19); he speaks the truth in everything he says (Prov. 30:5). The notion that he would be untruthful and err is contradictory to everything Scripture tells us about him.

However, Scripture also tells us that the word of God comes through the minds and mouths of men. Does this not mean that it will inevitably contain some mistakes? After all, ‘To err is human.’ If so, to use an old illustration, is it not more appropriate to think of the Bible as though it were a slightly scratched gramophone record? Or, in more contemporary terms, is the Bible not like a digitized version of an old recording— despite deficiencies, the music can still be heard, and if we listen with care we can make out the words quite well.

But two obvious considerations need to be remembered.

First, strictly speaking, ‘to err’ is not so much human as it is fallen. Second, not everything said by humans involves error. Life revolves round the fact that people speak the truth, that what they say is not riddled with mistakes. A person can go through the whole day without making a single erroneous statement. And societies function well only where a premium is placed on truth telling. Much of what we say and write is, in a fairly obvious sense, error free.

It is surely then within the power of God to preserve the authors of Scripture from error.

So the assumption that the Scriptures inevitably contain errors because written by men is false.

But there is a further consideration, in addition to that of the logic of our theology. The books of Scripture specifically affirm the truthfulness of what is written; those who appear in their narratives share that perspective. Jesus himself spoke of God’s word as ‘truth’. Almost in passing he stated that ‘Scripture cannot be broken’ (John 10:35)—and it is often in such passing comments that our real convictions come to the surface. Continue reading