Article by Kenneth Richard Samples: Countdown to Reformation Day: Responding to Objections to Sola Scriptura (original source here)

Article by Kenneth Richard Samples: Countdown to Reformation Day: Responding to Objections to Sola Scriptura (original source here)

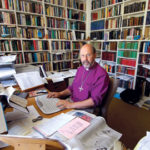

Kenneth Richard Samples is senior scholar at Reasons to Believe (a science-faith think tank) and an adjunct instructor of apologetics at Biola University. This article is an excerpt from Kenneth Richard Samples, A World of Difference: Putting Christian Truth-Claims to the Worldview Test (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2007), 120-27.

The authority of Scripture holds supreme importance in a Christian worldview, especially for Protestant evangelicals who believe that their faith and the way they live depend upon Scripture. Other branches of Christendom and skeptics, such as the convert to Roman Catholicism Peter Kreeft, sometimes raise objections to this crucial distinction. (1) They suggest that this principle is incoherent or unworkable. Responses to seven common objections explain how sola scriptura impacts Christian theology.

Objection #1: Scripture itself does not teach the principle of sola scriptura; therefore, this principle is self-defeating.

Response: The doctrine of sola scriptura need not be taught formally and explicitly. It may be implicit in Scripture and inferred logically. Scripture explicitly states its inspiration in 2 Timothy 3:15-17, and its sufficiency is implied there as well. This passage contains the essence of sola scriptura, revealing that Scripture is able to make a person wise unto salvation. And it includes the inherent ability to make a person complete in belief and practice.

Scripture has no authoritative peer. While the apostle Paul’s reference in verse 16—to Scripture being “God-breathed”—specifically applies to the Old Testament, the apostles viewed the New Testament as having the same inspiration and authority (1 Tim. 5:18; Deut. 25:4 and Luke 10:7; 2 Pet. 3:16). The New Testament writers continue, mentioning no other apostolic authority on par with Scripture. Robert Bowman notes: “The New Testament writings produced at the end of the New Testament period direct Christians to test teachings by remembering the words of the prophets (OT) and apostles (NT), not by accessing the words of living prophets, apostles, or other supposedly inspired teachers (Heb. 2:2-4; 2 Pet. 2:1; 3:2; Jude 3-4, 17).” (2)

Scriptural warnings such as “do not go beyond what is written” (1 Cor. 4:6) and prohibitions against adding or subtracting text (Rev. 22:18-19) buttress the principle that Scripture stands unique and sufficient in its authority.

Christ held Scripture in highest esteem. The strongest scriptural argument for sola scriptura, however, is found in how the Lord Jesus Christ himself viewed and used Scripture. A careful study of the Gospels reveals that he held Scripture in the highest regard. Jesus said: “The Scriptures cannot be broken” (John 10:35); “Your word is truth” (John 17:17); “Not the smallest letter, not the least stroke of a pen, will by any means disappear from the Law” (Matt. 5:18); and “It is easier for heaven and earth to disappear than for the least stroke of a pen to drop out of the Law” (Luke 16:17).

Christ appealed to Scripture as a final authority. Jesus even asserted that greatness in heaven will be measured by obedience to Scripture (Matt. 5:19) while judgment will be measured out by the same standard (Luke 16:29-31; John 5:45-47). He used Scripture as the final court of appeal in every theological and moral matter under dispute. When disputing with the Pharisees on their high view of tradition, he proclaimed: “Thus you nullify the word of God by your tradition” (Mark 7:13).

Because Scripture came from God, Jesus considered it binding and supreme, while tradition was clearly discretionary and subordinate. Whether tradition was acceptable or not depended on God’s written Word. This recognition by Christ of God’s Word as the supreme authority supplies powerful evidence for the principle of sola scriptura.

When Jesus was tested by the Sadducees concerning the resurrection, he retorted, “You are in error because you do not know the Scriptures” (Matt. 22:29). When confronted with the devil’s temptations, he responded three times with the phrase, “It is written,” followed by specific citations (Matt. 4:4-10). In this context, Jesus corrects Satan’s misuse of Scripture. Theologian J. I. Packer says of Jesus: “He treats arguments from Scripture as having clinching force.” (3)

Christ deferred to Scripture. Jesus based his ethical teaching upon the sacred text and deferred to its authority in his Messianic ministry (Matt. 19:18-19; Mark 10:19; Luke 18:20). His very destiny was tied to biblical text: “The Son of Man will go just as it is written” (Matt. 26:24). “This is what is written: The Christ will suffer and rise from the dead on the third day” (Luke 24:46). Even while dying on the cross, Jesus quoted Scripture (see Matt. 27:45, cf. Ps. 22:1). His entire life, death, and resurrection seemed to be arranged according to the phrase, “The Scriptures must be fulfilled” (Matt. 26:56; Luke 4:21; 22:37).

Clearly, Christ accepted Scripture as the supreme authority and subjected himself to it (Matt. 26:54; Luke 24:44; John 19:28). Jesus did not place himself above Scripture and judge it; instead he obeyed God’s Word completely. A follower of Christ can do no less. A genuinely biblical worldview requires Scripture to be the supreme authority.

Objection #2: The earliest Christians didn’t have the complete New Testament. Therefore, references to Scripture by Jesus and his apostles apply only to the Old Testament.

Response: This objection fails for four reasons. Continue reading

Article: The Suffering and the Glory of Psalm 22 by W. Robert Godfrey (original source

Article: The Suffering and the Glory of Psalm 22 by W. Robert Godfrey (original source  Article by Dr. Michael Reeves, president and professor of theology at Union School of Theology in Oxford, England. He is author of several books, including Rejoicing in Christ, Delighting in the Trinity and Why the Reformation Still Matters. (original source

Article by Dr. Michael Reeves, president and professor of theology at Union School of Theology in Oxford, England. He is author of several books, including Rejoicing in Christ, Delighting in the Trinity and Why the Reformation Still Matters. (original source  Article by Dr. Steve Lawson:

Article by Dr. Steve Lawson: Article by Dr. Jason Allen, president of Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Mo. He writes regularly at jasonkallen.com (original source

Article by Dr. Jason Allen, president of Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary in Kansas City, Mo. He writes regularly at jasonkallen.com (original source  While I do not hold to pre-millennialism (as stated below) this is an excellent article by Pastor Anthony Wood of Mission Bible Church, Tustin, California, regarding doctrinal unity (original source

While I do not hold to pre-millennialism (as stated below) this is an excellent article by Pastor Anthony Wood of Mission Bible Church, Tustin, California, regarding doctrinal unity (original source  If you want a quick-but-tedious way to separate some of the shallower evanjellyfish from the more theologically-serious evangelicals in your circle of friends, here’s a simple method: call N.T. Wright a heretic. It’s quick because the blowback you will surely experience can be timed in microseconds. It’s tedious because you will be subjected to a series of overweeningly shrill diatribes, accompanied by confident insinuations that anyone who says such a thing is a divisive dolt. But a more effective method is difficult to find.

If you want a quick-but-tedious way to separate some of the shallower evanjellyfish from the more theologically-serious evangelicals in your circle of friends, here’s a simple method: call N.T. Wright a heretic. It’s quick because the blowback you will surely experience can be timed in microseconds. It’s tedious because you will be subjected to a series of overweeningly shrill diatribes, accompanied by confident insinuations that anyone who says such a thing is a divisive dolt. But a more effective method is difficult to find.