…a word or two about the Trinity. Yes, the Trinity is part of a heritage of Christian understanding that all Christendom has received ever since the fourth century but it has always proved a problem to teach. In fact and I say, straight away, that there isn’t a good way of teaching it because it’s a reality for which there is no parallel. And realities for which there is no parallel are very difficult to express in words and equally, difficult to illustrate.

We’re used, I suppose, to the Sunday school illustrations. A teacher will tell the class, “Well, the Trinity is like water. It has three forms: liquid, steam, and ice.” And then there’s another illustration which was very widely used in England, I don’t know whether it’s still widely used over here. But, again, this is Sunday school stuff. You know how the clover leaf is. There are three little clover leaves as it were bound together by a single stalk, that’s how God is. One cloverleaf, three clover leaves, three in one.

You can see, I’m sure, what’s wrong with both of those illustrations. Neither of them makes the point that here we are talking about three persons. Each of them depersonalizes God in a way which really means, I think, that the kids in Sunday school lose more than they gain by being presented with that illustration. It encourages them to think of God as a thing rather than as three persons to each of whom one should be relating.

When I have to teach the Trinity, I offer a couple of different illustrations which try to do justice to the thought that there are three persons here. One of them is the illustration of a family. Now I know that three persons related in a family, whoever they are, are three distinct persons and not, in any sense, one person but they are one family. So, think of the three persons as related in the unchanging way that folk are related in a family. A father is always father in relation to sons and daughters. There’s a pattern there which doesn’t change and so it goes on with other family relationships. The relationship remains the same and that’s what I’m trying to illustrate by using that illustration which a number of theologians these days are working with because they think it’s the best illustration that’s available to us.

My other illustration is purely Packer and may simply be second rate, I’m not sure but, think in terms of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit as a team – a team in the same sense that in hockey or in soccer. The 11 players form a team.

Now, how do you define a team. Well, each player is related to 10 others in a way which remains the same whatever is going on in the game. The goalkeeper is always a goalie and the forwards and the backs, they’re related to each other and they are supposed to mark each other and keep together in a pattern. Whatever is happening in the game as the ball goes up and down or the puck if it’s hockey that you’re thinking of. And in the way in the revelation of God that you have in the New Testament, well the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit are always are related to each other in the same way. That, I believe, is the best concept to work with when we are thinking about God and the way that the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit are working for the fulfillment of the Father’s plan.

The Father always does what he does through the Son by the power of the Holy Spirit. The Lord Jesus, our divine Savior, always does what He does on the one hand in obedience to the Father’s direction. He made it very plain when he was on earth that everything that He said and did was in obedience to the Father’s direction. And at the same time, now that he is gone from this world, He works through the Holy Spirit doing everything that he does in our human lives.

So, there you have a constant relational pattern and you identify each of the three persons by stating how He, let’s say He for the moment because God is genderless. Everything that’s involved in masculinity and femininity is involved in God’s being, but God isn’t one as distinct from the other. No, but everything, as I say, God does in this world is done by this three-fold pattern of action, which is a pattern of togetherness, as you can see, and explains what is meant by talking about one God. To my mind, this is the most helpful of the illustrations that is available. If you don’t agree, never mind. It’s only a Packer illustration and I’ve never heard it used by anyone else.

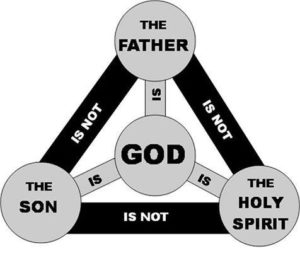

But anyway, what we can agree on even if we don’t attach much weight to any of the illustrations, is that here you have the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit, three persons, who yet are one God.

There is at least one Scripture that makes this perfectly explicit with no room for doubt. It’s Jesus’ words recorded right at the end of Matthew’s gospel when He’s giving the church, well, the apostles and through the apostles, the church, their marching orders, which is of course our marching orders – make disciples of all the nations baptizing them, he says, in the name.

Now, name is singular, not in the ‘names’ but in ‘the name.’ So this is one name. In the name of the Father and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit, three persons, one name. That’s the foundational scripture, as I say of all the scriptures that refer to the three persons together. It seems to me that the clearest and solidest in the sense of being foundational, that’s the Lord’s directive. Every disciple is to be baptized and baptized in that three-fold or trio name. So, there we have the Trinity.