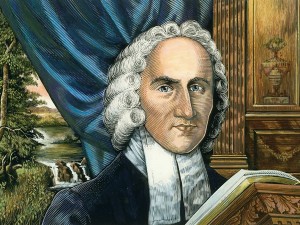

In a short article entitled, “Cautious Observations on the Existence of Evil” Sam Storms shares a few thoughts of his own before drawing from those of Jonathan Edwards:

In a short article entitled, “Cautious Observations on the Existence of Evil” Sam Storms shares a few thoughts of his own before drawing from those of Jonathan Edwards:

In the endless dialogue on why a good and powerful God would permit the existence of evil, no one has provided a more cogent and biblical explanation than Jonathan Edwards. It may not answer all our questions; in fact, it even raises a few new ones. But my sense is that this is as close as we’ll ever come to understanding in small measure a mystery that is ultimately beyond our grasp.

That being said, let me set forth a few cautious observations about the existence of evil before we look at Edwards’s proposal.

First, God is good in all he does, even when we explore the relationship of his will to the existence of evil. In him there is no darkness. Although he willed that evil exist, he is not evil or unrighteous in his essential being or in any of his acts or decrees. Regardless of where one lands in this discussion, on this point there can be no equivocation: God is eternally and infinitely good. The existence of evil is no threat to the goodness or greatness of God.

Second, in terms of what evil is, in and of itself, God hates it. This isn’t to say he doesn’t permit or ordain it or that he cannot use it for our good and his glory. It is simply to say that at the heart of this mystery is that God governs evil at the same time he is grieved by it. Evil is not in the slightest degree less evil nor is God in the slightest degree less good simply because God wills that evil exist. This will only make sense if we understand that whereas God hates evil for what it is, in itself (absolutely and simply), he nevertheless wills that evil be for the sake of what he can accomplish through it for the glory of his name and the ultimate good of his people. Thus, with a view to the greater glory of God, he is pleased to ordain his own displeasure. What displeases him because of its intrinsic wickedness, he either decrees or permits because of its place in the universal scheme of his purposes in Christ.

Third, since God hates evil, so should we. No explanation or account for the existence of evil can ever be used to justify our sin or be allowed to diminish our opposition to evil in all its many manifestations. The bottom line is this: if you find yourself increasingly content with evil, if you find yourself less offended with evil as time passes, if you find yourself less inclined to come to the aid of those who are its victims, you have not properly understood the Scriptures and your theory of the reason or cause for the existence of evil is fatally flawed. Any account for the existence of evil that does not energize Christians to work against it or does not elicit compassion for those who are suffering from its effects is seriously, if not fatally, flawed.

Fourth, God is sovereign over evil. It is never outside his control. Although this raises the question of why, if he is sovereign over it, he does not eliminate it, there can be no doubt that evil is subject to his power and purposes. God could have prevented the existence of evil from the beginning and could at any moment eradicate all evil from the universe. He is not limited by evil or frustrated by its presence. Having said that, we must be careful never to suggest that evil is intrinsically anything less than evil simply because we know it somehow, mysteriously, serves a purpose in God’s plan for human history.

Fifth, God will judge and punish evil. If nothing else makes sense when it comes to the existence of evil, rest assured that one day God will put the world to rights. One day God will expose every lie and vindicate every truth. One day evil and its unrepentant perpetrators will be brought to account. Justice is inevitable. Hell is real.

We are now ready to take note of how Edwards explained the existence of sin and evil. [I have taken the liberty of smoothing out Edwards’ prose in order to bring greater clarity to his theological argument. The full entry in his Miscellanies from which this has been taken can be found in Jonathan Edwards, The “Miscellanies,” edited by Thomas A. Schafer (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), no.348, pp. 419-20.]

“It is a proper and excellent thing for infinite glory to shine forth; and for the same reason, it is proper that the shining forth of God’s glory should be complete; that is, that all parts of his glory should shine forth, that every beauty should be proportionably effulgent, that the beholder may have a proper notion of God. It is not proper that one glory should be exceedingly manifested, and another not at all, for then the effulgence would not answer the reality.”

Edwards argues elsewhere that it is more than “proper” and “excellent” that God’s glory shine forth in its fullness, it is essential. This isn’t because something other than and outside God requires it of him. Rather, it is the very nature of divine glory that it tends toward self-expression and expansion, not in the sense of growth or quantitative increase, but manifestation and display for the sake of the joy of God’s creatures in it. Not only that, but it is “proper” that all of God’s glory be seen that we may know God as he truly is and not simply in part. If one or several divine attributes were disproportionately dominant in their display (and others barely noted at all), an imbalanced and inaccurate view of God would emerge (this is what Edwards meant when he said that otherwise “the effulgence would not answer the reality”). He continues:

“Thus it is necessary that God’s awful majesty, his authority and dreadful greatness, justice, and holiness, should be manifested. But this could not be, unless sin and punishment had been decreed; so that the shining forth of God’s glory would be very imperfect, both because these parts of divine glory would not shine forth as the others do, and also the glory of his goodness, love, and holiness would be faint without them; nay, they could scarcely shine forth at all.”

In using the word “necessary” he is not suggesting that sin, considered in and of itself, has a right or inherent claim on existence. Rather, sin was “necessary” in the sense that in its absence there would be no occasion for the display of his righteous wrath, justice, and holiness as that in God which requires punishment (or at least no display sufficient for a “complete” or true knowledge of what God is like and why he is glorious). And without a revelation (or “shining forth”) of the wrath that sin deserves there would scarcely be a revelation of the true and majestic depths of goodness, love, and grace that deliver us from it. Thus he concludes:

“If it were not right that God should decree and permit and punish sin, there could be no manifestation of God’s justice in hatred of sin or in punishing it, . . . or in showing any preference, in his providence, of godliness before it. There would be no manifestation of God’s grace or true goodness, if there was no sin to be pardoned, no misery to be saved from. No matter how much happiness he might bestow, his goodness would not be nearly as highly prized and admired. . . . and the sense of his goodness heightened.

So evil is necessary if the glory of God is to be perfectly and completely displayed. It is also necessary for the highest happiness of humanity, because our happiness consists in the knowledge of God, and the sense of his love. And if the knowledge of God is imperfect (because of a disproportionate display of his attributes), the happiness of the creature must be proportionably imperfect.”

John Piper:

John Piper: