we will celebrate Reformation Sunday as a day on the calendar when we remember what was undoubtedly, the greatest move of God outside the pages of the Scripture. Entire countries in Europe were brought under the sound of the true biblical Gospel.

The formal principle of the Reformation: Sola Scriptura (Scripture Alone)

The material principle of the Reformation: Sola Fide (Justification by Faith Alone)

Many “Protestant” Churches today have forgotten what it is they were protesting, and this has led to a very current need to re-evangelize the Church as to some of the very basics of the Christian faith.

In our day, many people choose the Church they go to based on preferences rather than convictions. Much is made of styles of music and worship, what kind of youth and toddler ministry is available, the length of the service, the likeability of the pastor, and adequate parking. Of course, none of these things are mentioned in Scripture, and yet they are things very important to us in a consumer driven society where the customer is king and choices mean everything.

I have much sympathy with the need to listen to people and address concerns, but I would like us to climb a little higher in our thinking to move from preference to conviction. In that regard, I would like to identify two convictions that should be at play in our thinking:

Defining terms: a preference is something that given a choice, we find to be more pleasing or practical than another. One could prefer vanilla to chocolate; jazz to opera, the color red rather than blue, etc.

A conviction is a fixed or firm belief based on knowing the rightness of a position. Convictions are often seen as a new kind of heresy in modern American culture, and yet, the Bible is given to us to convince us of God’s thoughts on an issue, and our role as recipients of this revelation is to be renewed in our mind so that we align our thinking with His.

Convictions are good if they are based on God’s revelation; if not, they can be mere tradition. The traditionalist’s anthem is always “don’t confuse me with the facts. I’ve already made up my mind.”

In contrast, the Christian should always be prepared to hold up their beliefs to the light of Scripture to see if the position is based on a true interpretation. This leads us to the first conviction I would like us to consider this morning: Continue reading

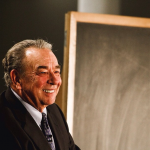

From Tabletalk Magazine, September, 2009, Dr. R. C. Sproul writes:

From Tabletalk Magazine, September, 2009, Dr. R. C. Sproul writes: