The first of the two debates from London last year. Adnan Rashid debates Dr. James White on one of the most important topics of our time – Is the Bible Corrupted?

Found here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dlGZdiSnuxU

by” is clearly illustrated in this instance. In Italian the two words are virtually identical, both in spelling and pronunciation. They thus involve a play on words. But when translated into other languages, the word-play vanishes. The meaning, on one level, is the same, but on another level it is quite different. Precisely because it is no longer a word-play, the translation doesn’t linger in the mind as much as it does in Italian. There’s always something lost in translation. It’s like saying in French, “don’t eat the fish; it’s poison.” The word ‘fish’ in French is poisson, while the word ‘poison’ is, well, poison. There’s always something lost in translation.

by” is clearly illustrated in this instance. In Italian the two words are virtually identical, both in spelling and pronunciation. They thus involve a play on words. But when translated into other languages, the word-play vanishes. The meaning, on one level, is the same, but on another level it is quite different. Precisely because it is no longer a word-play, the translation doesn’t linger in the mind as much as it does in Italian. There’s always something lost in translation. It’s like saying in French, “don’t eat the fish; it’s poison.” The word ‘fish’ in French is poisson, while the word ‘poison’ is, well, poison. There’s always something lost in translation.

But how much is lost? Here I want to explore five more myths about Bible translation.

Myth 1: The Bible has been translated so many times we can’t possibly get back to the original.

This myth involves a naïve understanding of what Bible translators actually did. It’s as if once they translated the text, they destroyed their exemplar! Sometimes folks think that translators who were following a tradition (such as the KJV and its descendants, the RV, ASV, RSV, NASB, NKJB, NRSV, and ESV) really did not translate at all but just tweaked the English. Or that somehow the manuscripts that the translators used are now lost entirely.

The reality is that we have almost no record of Christians destroying biblical manuscripts throughout the entire history of the Church. And those who translated in a tradition both examined the English and the original tongues. Decent scholars improved on the text as they compared notes and manuscripts. Finally, we still have almost all of the manuscripts that earlier English translators used. And we have many, many more as well. The KJV New Testament, for example, was essentially based on seven Greek manuscripts, dating no earlier than then eleventh century. Today we have about 5800 Greek manuscripts of the New Testament, including those that the KJV translators used. And they date as early as the second century. So, as time goes on, we are actually getting closer to the originals, not farther away.

Myth 2: Words in red indicate the exact words spoken by Jesus of Nazareth.

Scholars have for a long time recognized that the Gospel writers shape their narratives, including the sayings of Jesus. A comparison of the Synoptics reveals this on almost every page. Matthew quotes Jesus differently than Mark does who quotes Jesus differently than Luke does. And John’s Jesus speaks significantly differentyly than the Synoptic Jesus does. Just consider the key theme of Jesus’ ministry in the Synoptics: ‘the kingdom of God’ (or, in Matthew’s rendering, often ‘the kingdom of heaven’). Yet this phrase occurs only twice in John, being replaced usually by ‘eternal life.’ (“Kingdom of God” occurs 53 times in the Gospels, only two of which are in John; “kingdom of heaven” occurs 32 times, all in Matthew. “Eternal life” occurs 8 times in the Synoptics, and more than twice as often in John.) The ancient historians were far more concerned to get the gist of what a speaker said than they were to record his exact words. And if Jesus taught mostly, or even occasionally, in Aramaic, since the Gospels are in Greek the words by definition are not exact.

A useful distinction is made between the very words of Jesus and very voice of Jesus, known as ipsissima verba and ipsissima vox, respectively. Only rarely can we say that we have the very words of Jesus, but we can be far more confident that what is recorded in red letters in translations is at least the very voice of Jesus. Again, if ancient historians were not as concerned to get the words exactly right, we should not put them into a modernist straitjacket in which we expect them to be something they were never intended to be.

Myth 3: Heretics have severely corrupted the text.

This myth is usually promoted by King James Only folks who assume that the manuscripts that came from Egypt were terribly corrupted. A more sophisticated approach seeks to demonstrate this in passage after passage. For example, would orthodox scribes begin the quotation of Isaiah 40.3 and Malachi 3.1 in Mark 1.2 with “As it is written in Isaiah the prophet”? The alternative reading, found in the majority of manuscripts, reads “As it is written in the prophets.” But the earliest, most widespread reading is “in Isaiah the prophet.” It looks as though the later scribes were troubled by this attribution and they ‘corrected’ it to be more generic so as to include Malachi.

What is overlooked in the approach that assumes that the earlier manuscripts were corrupted and produced by heretics is the fact that virtually all Gospels manuscripts harmonize. That is, in parallel passages between two or more Gospels, virtually all manuscripts, from time to time, change the wording in one Gospel so that it duplicates the wording in another. Would heretics do this? It represents rather a high view of scripture—or, as Paul said in another context, zeal that is not according to knowledge. Further, the great majority of these harmonizations are either found in isolated manuscripts or in later manuscripts. This tells us that the tendencies of the earliest scribes was to harmonize, but because such harmonizations are done sporadically and in isolation they are easily detected. And later scribes produced their copies in great quantities in a heavily concentrated area, resulting in a more systematic harmonization—again, something that is easily detected.

This finds an apt analogy in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings. When the beleaguered hobbits meet the dark stranger, Strider, at the Prancing Pony Inn, they are relieved to learn that he is on their side. He is Aragorn, and he tells them that if he had been their enemy he could have killed them easily.

There was a long silence. At last Frodo spoke with hesitation, “I believed that you were a friend before the letter came,” he said, “or at least I wished to. You have frightened me several times tonight, but never in the way that servants of the Enemy would, or so I imagine. I think one of his spies would—well, seem fairer and feel fouler, if you understand.”

Likewise, the readings of the oldest manuscripts often has a way of making Christians nervous, but in the end it seems fouler but feels fairer.

Myth 4: Orthodox scribes have severely corrupted the text.

This is the opposite of myth #3. It finds its most scholarly affirmation in the writings of Dr. Bart Ehrman, chiefly The Orthodox Corruption of Scripture and Misquoting Jesus. Others have followed in his train, but they have gone far beyond what even he claims. For example, a very popular book among British Muslims (The History of the Qur’anic Text from Revelation to Compilation: a Comparative Study with the Old and New Testaments by M. M. Al-Azami) makes this claim:

The Orthodox Church, being the sect which eventually established supremacy over all the others, stood in fervent opposition to various ideas ([a.k.a.] ‘heresies’) which were in circulation. These included Adoptionism (the notion that Jesus was not God, but a man); Docetism (the opposite view, that he was God and not man); and Separationism (that the divine and human elements of Jesus Christ were two separate beings). In each case this sect, the one that would rise to become the Orthodox Church, deliberately corrupted the Scriptures so as to reflect its own theological visions of Christ, while demolishing that of all rival sects.”

This is a gross misrepresentation of the facts. Even Ehrman admitted in the appendix to Misquoting Jesus, “Essential Christian beliefs are not affected by textual variants in the manuscript tradition of the New Testament.” The extent to which, the reasons for which, and the nature of which the orthodox scribes corrupted the New Testament has been overblown. And the fact that such readings can be detected by comparison with the readings of other ancient manuscripts indicates that the fingerprints of the original text are still to be seen in the extant manuscripts.

Myth 5: The deity of Christ was invented by emperor Constantine.

This myth was heavily promoted in Dan Brown’s Da Vinci Code. He, in turn, based his allegedly true statements (even though the book was a novel, he claimed that it was based on historical facts) on Holy Blood, Holy Grail (by Michael Baigent, Richard Leigh, and Henry Lincoln). The evidence, in fact, that the deity of Christ is to be found in the original New Testament is overwhelming. A look at some of the early papyri shows this. In passage after passage, the deity of Christ shines through the pages of the New Testament—and in manuscripts that significantly predate Constantine. For example, P66, a papyrus from the late second century, says what every other manuscript in John 1.1 says—“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” It predates the Council of Nicea (AD 325), which these skeptics claim is the time when Constantine invented Christ’s divinity, by about 150 years! P46, a papyrus dated to c. AD 200, plainly speaks of Christ’s divinity in Hebrews 1.8. The list could go on and on. Altogether, we have more than fifty Greek New Testament manuscripts that are prior to Constantine’s reign. Not one of them denies the deity of Christ.

To see some of the details that expose these myths, consider the following books:

Rob Bowman and Ed Komoszewski, Putting Jesus in His Place: The Case for the Deity of Christ

Ed Komoszewski, James Sawyer, and Daniel B. Wallace, Reinventing Jesus

Daniel B. Wallace, editor, Revisiting the Corruption of the New Testament.

Eberhard Nestle

Eberhard Nestle

From wikipedia: The first edition published by Eberhard Nestle in 1898 combined the readings of the editions of Tischendorf, Westcott and Hort and Weymouth, placing the majority reading of these in the text and the third reading in the apparatus. In 1901, he replaced the Weymouth New Testament with Bernhard Weiss’s text. In later editions, Nestle began noting the attestation of certain important manuscripts in his apparatus.

Eberhard’s son Erwin Nestle took over after his father’s death and issued the 13th edition in 1927. This edition introduced a separate critical apparatus and began to abandon the majority reading principle.

Kurt Aland

Kurt Aland

Kurt Aland became the associate editor of the 21st edition in 1952. At Erwin Nestle’s request, he reviewed and expanded the critical apparatus, adding many more manuscripts. This eventually led to the 25th edition of 1963. The great manuscript discoveries of the 20th century had also made a revision of the text necessary and, with Nestle’s permission, Aland set out to revise the text of Novum Testamentum Graece. Aland submitted his work on NA to the editorial committee of the United Bible Societies Greek New Testament (of which he was also a member) and it became the basic text of their third edition (UBS3) in 1975, four years before it was published as the 26th edition of Nestle-Aland.

The NA27 edition was published in 1993, and now Dr. James White explains why the newly published edition of the Greek New Testament (the Nestle Aland 28th Edition) is a VERY good thing:

For those interested, the new edition is available to purchase here.

Ok – now I am confused… It seems that rumours rather than facts are flying round the internet at an alarming rate today. A few hours ago, believing it to be fraudulent. Now it seems that this information is not accurate at all and that in fact they will. Stayed tuned for accurate news as this story develops.

Ok – now I am confused… It seems that rumours rather than facts are flying round the internet at an alarming rate today. A few hours ago, believing it to be fraudulent. Now it seems that this information is not accurate at all and that in fact they will. Stayed tuned for accurate news as this story develops.

Hello! Hello! Main Stream Media… Hello! Anybody Home????

Hello! Hello! Main Stream Media… Hello! Anybody Home????

I just wonder if the major news media outlets will broadcast this news as loudly and as widely as last week’s. Please forgive my skepticism regarding this, but somehow, I doubt it.

the Payzant Distinguished Professor of New Testament at Acadia University and Divinity College, sent to me earlier today. He said that Helmut Koester (Harvard University), Bentley Layton (Yale University), Stephen Emmel (University of Münster), and Gesine Robinson (Claremont Graduate School)–all first-rate scholars in Coptic studies–have weighed in and have found the fragment wanting. No doubt Francis Watson’s comprehensive work showing the fragment’s dependence on the Gospel of Thomas was a contributing factor for this judgment, as well as the rather odd look of the Coptic that already raised several questions as to its authenticity.

Dr. James White writes, “Now, that doesn’t mean the saga is over for two reasons: 1) the fragment could be rehabilitated by the release of further relevant information concerning its provenance, and 2) the MSM (main stream media) is far more interested in posting stuff that is against Christianity than corrections and retractions.”

The first ever question in the Universe was uttered by the crafty serpent to Adam’s wife Eve in the Garden of Eden, why would he ever need to change what is obviously a winning tactic? He knows that unless doubt is countered, it will lead to skepticism, and in due course, outright unbelief.

The first ever question in the Universe was uttered by the crafty serpent to Adam’s wife Eve in the Garden of Eden, why would he ever need to change what is obviously a winning tactic? He knows that unless doubt is countered, it will lead to skepticism, and in due course, outright unbelief.

In former days it was just scholars who needed to be aware of this kind of material. Yet now that the blatant attacks on the Bible have gone mainstream in the media through men like Dan Brown and Bart Ehrman, Christians in our day need to be armed with answers. Here’s what we know:

The Jews had an unparalleled reverence for the Scripture. As the book of Deuteronomy expresses it, “man shall not live by bread alone but by every word that proceeds out of the mouth of God.” Jesus quotes this verse in response to the devil’s first temptation in the wilderness (Matthew 4:4, Luke 4:4).

We can determine Christ’s view of Scripture with even greater certainty from His words in Matthew 22. In the context of quoting from the book of Genesis, He said, “…have you not read what was spoken to you by God…” (Matt. 22:31) According to Jesus, when the text of Genesis is read, you are reading words spoken to you by God. To say that Jesus had a high view of the text of the Bible would be a huge understatement.

But that is not all. In Matthew 5:18, Jesus said, “For assuredly, I say to you, till heaven and earth pass away, one jot or one tittle will by no means pass from the law till all is fulfilled.” This is hugely significant. A “jot” is the Hebrew letter “yodh”, the 10th letter of the Hebrew alphabet. It is also the smallest letter. A “tittle” is the small decorative spur or point on the upper edge of the yodh. If you can imagine a tiny letter with a slightly visible decorative mark (similar to the dot used in the lower case letter “i” in our English language), the meaning of Christ’s statement becomes abundantly clear. Jesus was saying that not even the smallest letter or even a tiny mark above a Hebrew letter will ever disappear from God’s law, until all is fulfilled. He not only believed that inspiration extended to every word, but to every tiny mark on the page.

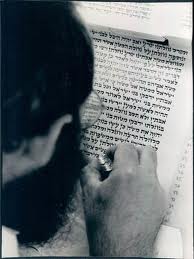

For an orthodox Jew, nothing was more sacred than the word of God. This meant that when it came to making copies of the Biblical text onto scrolls, each Jewish scribe was meticulous in the extreme, viewing his task as a high and holy calling. Tradition tells us that each scribe would actually take a bath before writing the name of God on a scroll, even if it appeared only a few words apart in a verse. Multiple references meant multiple baths!

As is the case in a number of other languages, each letter in Hebrew has a numerical value. This means that each line in the text could be given a numerical value, as did each page and each scroll. If the number total of the copied scroll was not the same as the original, the entire copy was burned. Similarly, if a letter even touched another letter, the copy would be destroyed and the scribe was asked to start his work all over again. Talk about precision!

Continue reading

Jonathan Dodson writes:

Jonathan Dodson writes:

Most people question the reliability of the Bible. You’ve probably been in a conversation with a friend or met someone in a coffee shop who said, “How can you be a Christian when the Bible has so many errors?”

How should we respond? What do you say?

Instead of asking them to name an error, I suggest you name one or two of them. Does your Bible contain errors? Yes. The Bible that most people possess is a translation of the Greek and Hebrew copies of copies of the original documents of Scripture. As you can imagine, errors have crept in over the centuries of copying. Scribes fall asleep, misspell, take their eyes off the manuscript, and so on. I recommend telling people what kind of errors have crept into the Bible. Starting with the New Testament, Dan Wallace, New Testament scholar and founder of the Center for the Study of New Testament Manuscripts, lists four types of errors in Understanding Scripture: An Overview of the Bible’s Origin, Reliability, and Meaning.

Types of Errors

1. Spelling and Nonsense Errors

These are errors that occur when a scribe wrote a word that makes no sense in its context, usually because they were tired or took their eyes off the page. Some of these errors are quite comical, such as “we were horses among you” (Gk. hippoi, “horses,” instead of ?pioi, “gentle,” or n?pioi, “little children”) in 1 Thessalonians 2:7 in one late manuscript. Obviously, Paul isn’t saying he acted like a horse among them. That would be self-injury! These kinds of errors are easily corrected.

2. Minor Changes

These minor changes are as small as the presence or absence of an article such as “the” or changed word order, which can vary considerably in Greek. Depending on the sentence, Greek grammar allows the sentence to be written up to 18 times, while still saying the same thing! So just because a sentence wasn’t copied in the same order, doesn’t mean that we lost the meaning.

3. Meaningful but Not Plausible

These errors have meaning but aren’t a plausible reflection of the original text. For example, 1 Thessalonians 2:9, instead of “the gospel of God” (the reading of almost all the manuscripts), a late medieval copy has “the gospel of Christ.” There is a meaning difference between God and Christ, but the overall manuscript evidence points clearly in one direction, making the error plain and not plausibly part of the original.

4. Meaningful and Plausible

These are errors that have meaning and that the alternate reading is plausible as a reflection of the original wording. These types of errors account for less than 1% of all variants and typically involve a single word or phrase. The biggest of these types of errors is the ending of the Gospel of Mark, which most contemporary scholars do not regard as original. Our translations even footnote that!

Is the Bible Reliable?

So, is the Bible reliable? Well, the reliability of our English translations depends largely upon the quality of the manuscripts they were translated from. The quality depends, in part, on how recent the manuscripts are. Scholars like Bart Ehrman have asserted that we don’t have manuscripts that are early enough. However, the manuscript evidence is quite impressive:

There are as many as 18 second-century manuscripts. If the Gospels were completed between AD 50–100, then this means that these early copies are within 100 years. Just recently, Dan Wallace announced that a new fragment from the Gospel of Mark was discovered dating back to the first century AD, placing it well within 50 years of the originals, a first of its kind. When these early manuscripts are all put together, more than 43% of the New Testament is accounted for from copies no later than the second century.

Manuscripts that date before AD 400 number 99, including one complete New Testament called Codex Sinaiticus. So the gap between the original, inerrant autographs and the earliest manuscripts is pretty slim. This comes into focus when the Bible is compared to other classical works that, in general, are not doubted for their reliability. In this chart of comparison with other ancient literature, you can see that the New Testament has far more copies than any other work, numbering 5,700 (Greek) in comparison to the over 200 of Suetonius. If we take all manuscripts into account (handwritten prior to printing press), we have 20,000 copies of the New Testament. There are only 200 copies of the earliest Greek work.

This means if we are going to be skeptical about the Bible, then we need to be thousands of times more skeptical about the works of Greco-Roman history. Or put another way, we can be a thousand times more confident about the reliability of the Bible. It is far and away the most reliable ancient document.

What to Say When Someone Says “The Bible Has Errors”

So, when someone asserts that the Bible has errors, we can reply by saying:

Yes, our Bible translations do have errors—let me tell you about them. But as you can see, less than 1% of them are meaningful and those errors don’t affect the major teachings of the Christian faith. In fact, there are a thousand times more manuscripts of the Bible than the most documented Greco-Roman historian by Suetonius. So, if we’re going to be skeptical about ancient books, we should be a thousand times more skeptical of the Greco-Roman histories. The Bible is, in fact, incredibly reliable.

Contrary to popular assertion, that as time rolls on we get further and further away from the original with each new discovery, we actually get closer and closer to the original text. As Wallace puts it, we have “an embarrassment of riches when it comes to the biblical documents.” Therefore, we can be confident that what we read in our modern translations of the the ancient texts is approximately 99% accurate. It is very reliable.

For Further Study

In order of easy to difficult:

My sermon and manuscript, “Is the Bible Inerrant?”

Can I Trust the Bible? (free preview), by R. C. Sproul

Understanding Scripture: An Overview of the Bible’s Origin, Reliability, and Meaning, edited by Wayne Grudem, C. John Collins, and Thomas Schreiner

The Inspiration and Authority of the Bible, by B.B. Warfield

Text of the New Testament, by Bruce Metzger and Bart Ehrman

This post originally appeared on Gospel-Centered Discipleship.

There is a meaningful and significant textual variant at Luke 23:34 in our Bibles. The variant has been placed in brackets in the following citation:

[But Jesus was saying, “Father, forgive them; for they do not know what they are doing.”] And they cast lots, dividing up His garments among themselves.

It may be something of a surprise to learn that many scholars (even those scholars who believe the Bible to be the very word of God) are not convinced that these words (attributed to Christ) were actually part of the original New Testament text.

Dr. James White is a critical consultant for the New American Standard Bible Update (1995). Here he is (below) discussing this verse with Alan Kurschner.

It really is a fascinating study, lasting just under an hour. Along the way, we learn a great deal about the field of textual criticism which seeks to ascertain the original words of the Bible.

Here is a link to the two graphics referred to in the program. The first is the textual data taken from Reuben Swanson, New Testament Greek Manuscripts: Luke (London, 1998) and the second is a blow up of the relevant portion of Codex Sinaiticus:

For those who would like to read a recent article on this same theme by Alan Kurschner, here is a link to check out.