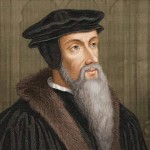

Article by Dr. Sinclair Ferguson (original source John Calvin seems to be at his most feisty when he writes on the sacraments. Against those who complain that infant baptism is a travesty of the Gospel, in the Institutes he stoutly insists, “these darts are aimed more at God than at us!” But a little reflection reveals he is also at his most thoughtful, and his analysis of sacramental signs can strengthen credobaptists as well as paedobaptists.

Article by Dr. Sinclair Ferguson (original source John Calvin seems to be at his most feisty when he writes on the sacraments. Against those who complain that infant baptism is a travesty of the Gospel, in the Institutes he stoutly insists, “these darts are aimed more at God than at us!” But a little reflection reveals he is also at his most thoughtful, and his analysis of sacramental signs can strengthen credobaptists as well as paedobaptists.

If repentance and faith are in view in baptism, how can infant baptism be biblical? Calvin responds: the same was true of circumcision (hence references to Jer. 4:4; 9:25; Deut. 10:16; 30:6), yet infants were circumcised.

How then can either sign be applicable to infants who have neither repented nor believed? Calvin’s central emphasis here is simple, but vital. Continue reading