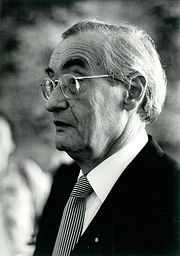

On Friday, February 24, 2012 Hugh Hewitt interviewed Professor Dan Wallace (pictured) concerning the announcement of a discovery of a first century papyri of the Gospel of Mark. Here is a transcript of the interview:

On Friday, February 24, 2012 Hugh Hewitt interviewed Professor Dan Wallace (pictured) concerning the announcement of a discovery of a first century papyri of the Gospel of Mark. Here is a transcript of the interview:

HH: I’m so pleased to begin with a conversation with Professor Daniel Wallace. He’s a professor of New Testament Studies at Dallas Theological Seminary. He’s a graduate of our wonderful friend up the road at Biola University, and Professor Wallace, welcome, thanks for making some time for us tonight.

DW: Well, thank you so much. It’s an honor to be on your show.

HH: I’ve got to tell you, Professor, you turned a lot of heads when you alluded in your recent debate with Bart Ehrman to a new manuscript, or fragment of a manuscript concerning the Gospel of Mark. I know you’ve got scholarly restrictions on what you can and cannot say, but can you tell the audience what you’re allowed to disclose about that?

DW: I’ll be happy to. First of all, there is a fragment of Mark, and it’s a very small fragment, not too many verses, but it’s definitely from Mark. And the most amazing thing about this is that it’s from the 1st Century. We don’t have any other New Testament manuscripts that are written within the same century that the Gospels and the rest of the New Testament were written in. This is the first. And it’s dated by one of the world’s leading paleographers, whose name I’m not allowed to reveal yet. It will be published in a book with six other manuscripts that are either probably or definitely from the 2nd Century in about a year from now. And this is very, very exciting news, frankly. To have a fragment from one of the Gospels that’s written during the lifetime of some of the eyewitnesses to the resurrection is just astounding.

HH: Now when you say verses, can you tell us how many verses are in the fragment?

DW: Well, not really. I can say we have fragments, some of our fragments are so small that it might be part of one verse. This is bigger than that. And we have some of these early papyri, this is on papyrus, that are as much as, well, P-46, which is our oldest manuscript, or was our oldest manuscript for Paul’s letters, has nine of Paul’s letters in it almost intact. That’s a pretty large papyrus. So all of our papyri are fragmentary because of the nature of the material, and because of the age of the material. There’s leaves that just got eaten away or just eroded. But this is one leaf, I should say, or part of one leaf. So it can’t be very many verses on it.

HH: Now in terms of what you know about it, does it correspond with the translations that have come down to us? In other words, will it confirm that the translations have integrity through the centuries?

DW: I think that yes, all of these fragments will do that. And here’s how they do it. It’s not a straight answer you can give to this, but I think it’s a very important answer to note. And that is that some of our earlier manuscripts are written by unprofessional scribes. And sometimes, those unprofessional scribes are sloppy in their spelling, or something like that. Others are written by professionally trained scribes, and they’re concerned with making pretty letters, and they often leave out words or add words by accident. But none of those places, in the last 135 years when we’ve been discovering New Testament papyri, there’s not a single place where any manuscript discovery of the last 135 years has introduced new wording to a passage that was not found in any other manuscripts before, that now scholars say this is authentic.

HH: Now why is it taking so long, Professor Wallace? And is there a threat of the repeat of the Dead Sea Scrolls fiasco, where it took forever to get the scrolls out?

DW: That’s a great question, but no, that is not the situation we’re facing here. Of course, you’re dealing with hundreds and hundreds of scrolls among the Dead Sea manuscripts. Here, we’re dealing with seven. It’s a matter of getting various scholars to be doing the work on it. And to do the work of paleography, which is dating the manuscript, and we need to get more than one scholar who has done this, even though the paleographer who has done it has a remarkable reputation, we need to get several paleographers to date it. And the manuscript needs to be truly vetted, or fully vetted. Once it gets published, you’ll get a number of discussions all over the scholarly world about it. But just to prepare a manuscript for publication that is this significant, the scholar has to measure each letter, and compare them to all the other letters. So if you have alpha or beta, you have to look at all of the betas and see how tall they are, how wide they are, and are they written the same way. That gives us information about the date, and it gives us information about the hand, whether it’s a professional hand or what’s called a documentary hand, somebody who’s not trained as a professional, but at least can write this stuff out accurately. All those things are very, very important. And it helps us with a number of things on that manuscript. Not just that, but we have to look the fibers of the papyrus, and sometimes, they’re not easy to see. You have fibers on one side, because papyrus leaves were laid out horizontally, and then the back side, they put more leaves that were stamped out vertically. And then they would naturally adhere to each other. And our New Testament manuscripts, which I think is really interesting, these early papyri were written on both sides, both the horizontal lines or the horizontal fibers, and the vertical fibers. And that was not what we find in the rest of the ancient world.

HH: I’m talking with Professor Daniel Wallace of Dallas Theological Seminary. Professor, has your paleographer been able to date it within a decade? I know it has to go through additional confirmation, additional scholarly comparison and contrasting, but the original paleographer, has he come up with it’s the 80 AD, or 70 AD?

DW: If he did, he would be a miracle worker. Paleography is not that precise unless you have a manuscript that says this scribe wrote this in the third year of Augustus, you know. Then, you can be pretty sure when he wrote it. But paleography, you can get these earlier manuscripts dated to within about 50 years, and that’s actually better than what you can do for many of the later manuscripts. We actually have better evidence for the earlier ones, because the changes in the handwriting were more rapid in the ancient world than they were in the medieval world. And so he can date it within 50 years.

HH: And that will put it in the 1st Century, though?

DW: Not only that it will possibly do so, but his understanding is it definitely is.

HH: So it can’t be any later than 51. All right, let me ask you about the other manuscripts, the other six manuscripts in addition to the fragment from Mark. Are they other Biblical transcriptions?

DW: Yes. All six of them are Biblical, but one is not exactly a Biblical text, which is really, in some respects, the most interesting. It’s a homily on Hebrews, Chapter 11, a sermon on Hebrews 11.

HH: That is fascinating.

DW: What makes that so interesting is the ancient church understood by about AD 180 in what’s called the Muratorian Fragment, or the Muratorian Canon, that the only books that could be read in churches must be those that are authoritative. To have a homily or a sermon on Hebrews means that whoever wrote that sermon considered Hebrews to be authoritative, and therefore, it could be read in the churches.

Continue reading →

Eberhard Nestle

Eberhard Nestle Kurt Aland

Kurt Aland

On Friday, February 24, 2012

On Friday, February 24, 2012