Justin Taylor:

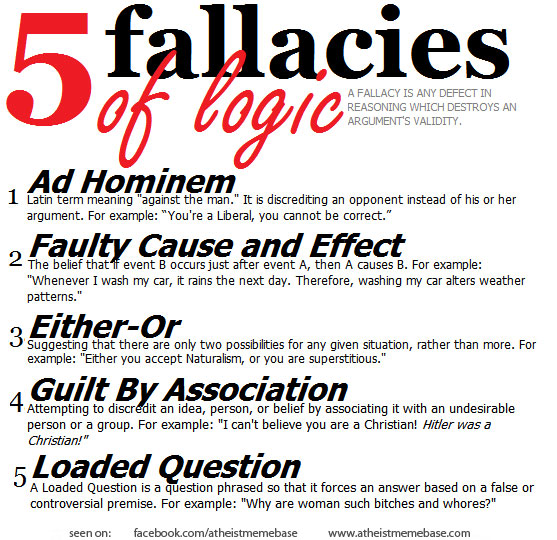

Michael Horton provides some which should be avoided when writing a theological paper in his classes (and, of course, in all of life!). I’ve reprinted below the ones that he lists (along with some images, which have some relevance to the fallacy in one way or another).

Ad Hominem

First and foremost we need to avoid the ubiquitous ad hominem (“to/concerning the person”) variety—otherwise known as “personal attacks.”

Poor papers often focus on the person: both the critic and the one being criticized. This is easier, of course, because one only has to express one’s own opinions and reflections. A good paper will tell us more about the issues in the debate than about the debaters. (This of course does not rule out relevant biographical information on figures we’re engaging that is deemed essential to the argument.)

Red Herring

Closely related are red-herring arguments: poisoning the well, where you discredit a position at the outset (a pre-emptive strike), or creating a straw man (caricature) that can be easily demolished.

“Barth was a liberal,” “Roman Catholics do not believe that salvation is by grace,” “Luther said terrible things about Jews and Calvin approved the burning of Servetus—so how could you possibly take seriously anything they say?”

It’s an easy way of dismissing views that may be true even though those who taught them may have said or done other things that are reprehensible.

Genetic Fallacy

Closely related is the genetic fallacy, which requires merely that one trace an argument or position back to its source in order to discount it.

Simply to trace a view to its origin—as Roman Catholic, Arminian, Lutheran, Reformed, Anabaptist/Baptist, etc.—is not to offer an argument for or against it. For example, we all believe in the Trinity; it’s not wrong because it’s also held by Roman Catholics. “Barth studied under Harnack and Herrmann, so we should already consider his doctrine of revelation suspect.” This assertion does not take into account the fact that Barth was reacting sharply against his liberal mentors and displays no effort to actually read, understand, and engage the primary or secondary sources.

Slippery Slope

Closely related to these fallacies is the all too familiar slippery slope argument. “Barth’s doctrine of revelation leads to atheism” or “Arminianism leads to Pelagianism” or “Calvinism leads to fatalism” would be examples. Even if one’s conclusion is correct, the argument has to be made, not merely asserted. The fact is, we often miss crucial moves that people make that are perfectly consistent with their thinking and do not lead to the extreme conclusions we attribute to them—not to mention the inconsistencies that all of us indulge. Honesty requires that you engage the positions that people actually hold, not conclusions you think they should hold if they are consistent.

If you’re going to make a logical argument that certain premises lead to a certain conclusion, then you need to make the case and must also be careful to clarify whether the interlocutor either did make that move or did not but (logically) should have.

Sweeping Generalization

Another closely related fallacy here is sweeping generalization. Until recently, it was common for historians to try to explain an entire system by identifying a “central dogma.” For example, Lutherans deduce everything from the central dogma of justification; Calvinists, from predestination and the sovereignty of God. Serious scholars who have actually studied these sources point out that these sweeping generalizations don’t have any foundation. However, sweeping generalizations are so common precisely because they make our job easier. We can embrace or dismiss positions easily without actually having to examine them closely. Usually, this means that a paper will be more “heat” than “light”: substituting emotional assertion for well-researched and logical argumentation.

“Karl Barth’s doctrine of revelation is anti-scriptural and anti-Christian” is another sweeping generalization. If I were to ask you in person why you think Barth’s view of revelation is “anti-scriptural anti-Christian,” you might answer, “Well, I think that he draws too sharp a contrast between the Word of God and Scripture—and that this undermines a credible doctrine of revelation.” “Good,” I reply, “now why do you think he makes that move?” “I think it’s because he identifies the ‘Word of God’ with God’s essence and therefore regards any direct identification with a creaturely medium (like the Bible) as a form of idolatry. It’s part of his ‘veiling-unveiling’ dialectic.” OK, now we’re closer to a real thesis—something like, “Because Barth interprets revelation as nothing less than God’s essence (actualistically conceived), he draws a sharp contrast between Scripture and revelation.” A good argument for something like that will allow the reader to draw conclusions instead of strong-arming the reader with the force of your own personality.

Begging the Question

Also avoid the fallacy of begging the question. For example, question-begging is evident in the thesis statement: “Baptists exclude from the covenant those whom Christ has welcomed.” After all, you’re assuming your conclusion without defending it. Baptists don’t believe that children of believers are included in the covenant of grace. That’s the very reason why they do not baptize them. You need an argument.

“It is perfectly logical and reasonable to examine a position, or the progression of a position, and work out its implications. Paul himself does this to the Corinthians.

“It is perfectly logical and reasonable to examine a position, or the progression of a position, and work out its implications. Paul himself does this to the Corinthians. Paradoxes are not contradictions. Contradiction is the hallmark of untruth. On the other hand, paradoxes reveal brilliant, dazzling, breath taking mystery.

Paradoxes are not contradictions. Contradiction is the hallmark of untruth. On the other hand, paradoxes reveal brilliant, dazzling, breath taking mystery.