In an article at ligonier.org entitled “The Doctrine of Scripture: Defining Our Terms” Kevin Gardner “The Bible says it. I believe it. That settles it.” If you don’t grasp what the Bible is and how it came to be, you’ll never fully grasp its meaning. Since the meaning of the Bible is vitally important to our faith and life, we will here briefly define a few key terms that relate to the doctrine of Scripture as the study of God’s Word written.

In an article at ligonier.org entitled “The Doctrine of Scripture: Defining Our Terms” Kevin Gardner “The Bible says it. I believe it. That settles it.” If you don’t grasp what the Bible is and how it came to be, you’ll never fully grasp its meaning. Since the meaning of the Bible is vitally important to our faith and life, we will here briefly define a few key terms that relate to the doctrine of Scripture as the study of God’s Word written.

Authority: The power the Bible possesses, having been issued from God, for which it “ought to be believed and obeyed” (Westminster Confession 1:4). Because of its divine author, the Bible is “the source and norm for such elements as belief, conduct, and the experience of God” (Westminster Dictionary of Theological Terms).

Autographs: The original texts of the biblical books as they issued from the hands of the human authors.

Canon: The authoritative list of inspired biblical books. Within a short time after Jesus’ death, the New Testament canon was affirmed by evaluating the Apostolicity, reception, and teachings of books, but ultimately, the canon is self-authenticating, as the voice of Christ is heard in it (John 10:27; WCF 1:5).

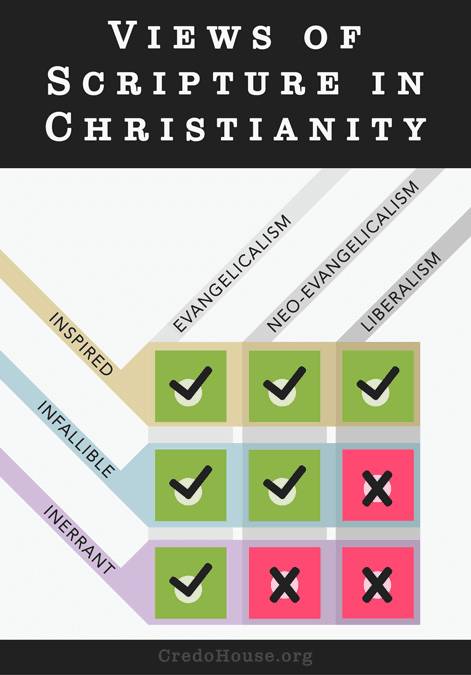

Inerrancy: The position that the Bible affirms no falsehood of any sort; that is, “it is without fault or error in all that it teaches,” in matters of history and science as well as faith (Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy). Inerrancy allows for literary devices, such as metaphors, hyperbole, round numbers, and colloquial expressions.

Infallibility: The position that the Bible cannot err or make mistakes, and that it “is completely trustworthy as a guide to salvation and the life of faith and will not fail to accomplish its purpose” (Westminster Dictionary). As the Christian church has traditionally taught, this doctrine is based on the perfection of the divine author, who cannot speak error.

Inspiration: The process by which God worked through the human authors of the Bible to communicate His revelation. The term derives from the Greek theopneustos, meaning “God-breathed” (2 Tim. 3:16), and refers to God as the ultimate source of the Scriptures.

Organic inspiration: The process by which God guided the human authors of Scripture, working in and through their particular styles and life experiences, so that what they produced was exactly what He wanted them to produce. The text is truly the work of the human authors—God did not typically dictate to them as to a stenographer—and yet the Lord stands behind it as the ultimate source.

Necessity: Refers to mankind’s need for God’s special revelation in the Scriptures in order to obtain knowledge of the gospel and the plan of salvation, which cannot be learned through the general revelation of nature and conscience.

Perspicuity: The clarity of the Bible; that is, that which is necessary to know and believe regarding life and salvation is “so clearly propounded, and opened in some place of Scripture or the other,” that anyone may understand them (WCF 1:7).

Scripture: From the Latin scriptura, meaning “writings”; refers to sacred texts, but more specifically, the Bible as the Word of God written.

Special revelation: The things that God makes known about Himself apart from nature and conscience (general revelation; cf. Rom. 1:19–21). These things, having to do with Christ and the plan of salvation, are found only in the Bible.

Sufficiency: All that is needed to know and believe regarding salvation and what pleases God is found in the Bible.

Verbal, plenary inspiration: The extending of God’s superintendence of the writing of Scripture down to the very choice of words, not merely to overarching themes or concepts; that is, “the whole of Scripture and all of its parts, down to the very words of the original,” were inspired (Chicago Statement).