the “Bible Answer Man, ” in his recent book Christianity in Crisis. Hanegraaff’s Charge resulted in a radical outburst of indignant cries directed not at Hinn but at Hanegraaff.

It seems that the only real and intolerable heresy today is the despicable act of calling someone a heretic. If the one accused is guilty of heresy, he or she will probably elicit more sympathy than his accuser. Anyone who cries “Heretic!” today risks being identified as a native of Salem, Massachusetts.

After Hanegraaff made his charge in print, a couple of things happened. One is that Hinn recanted his own teaching that there are nine persons in the Trinity and apologized to his hearers for that teaching. Such recantations are rare in church history, and it is gratifying that at least in this case on that point Hinn repented of his false teaching.

The second interesting footnote to the Hanegraaff-Hinn saga was the appearance of an editorial by the editor of a leading charismatic magazine in which Hanegraaff was castigated for calling Hinn a heretic. At the 1993 Christian Booksellers Association convention, I was present for and witness to a discussion between Hanegraaff and the magazine editor. I asked the editor a few questions. The first was, “Is there such a thing as heresy?” The editor acknowledged that there was. My second question was, “Is heresy a serious matter?” Again he agreed that it was. My next question was obvious. “Then why are you criticizing Hanegraaff for saying that Hinn was teaching heresy when even Hinn admits it now?”

The editor expressed concern about tolerance, charity, the unity of Christians, and matters of that sort. He expressed a concern about witch hunts in the evangelical church. My sentiments about that are clear. We don’t need to hunt witches in the evangelical world. There is no need to hunt what is not hiding. The “witches” are in plain view, every day on national television, teaching blatant heresy without fear of censure.

Consider the case of Jimmy Swaggart. For years Swaggart has publicly repudiated the orthodox doctrine of the Trinity. Swaggart was not challenged (to my knowledge) by his church for his heresy. He was censured for sexual immorality but not heresy. I guess this church regards romping with prostitutes in private a more serious offense than denying the Trinity before the watching world.

As I documented in The Agony of Deceit, Paul Crouch teaches heresy. So do Kenneth Copeland and Kenneth Hagin. These men seem to teach their heresies with impunity.

But what do we mean by heresy? Is every theological error a heresy? In a broad sense, every departure from biblical truth may be regarded as a heresy. But in the currency of Christian thought, the term heresy has usually been reserved for gross and heinous distortions of biblical truth, for errors so grave that they threaten either the essence (esse) of the Christian faith or the well-being (bene esse) of the Christian church.

Luther was excommunicated by Rome and declared a heretic for teaching justification by faith alone. Luther replied that the church had embraced a heretical view of salvation. The issue still burns as to who the heretic is.

In Luther’s response to Erasmus’ Diatribe, he acknowledged that many of the points at issue were trifles. They did not warrant rupturing the unity of the church. They could be “covered” by the love and forbearance that covers a multitude of sins. When it came to justification, however, Luther sang a different tune. He called justification the article upon which the church stands or falls, a doctrine so vital that it touches the very heart of the Gospel. A church that rejects justification by faith alone (and anathematizes it as a deadly heresy) is nolonger an orthodox church. Luther wasn’t shadow boxing on that issue; nor was the Reformation a mere misunderstanding between warring factions in the church. No teapot was big enough to contain the tempest it provoked.

In graduate school in Holland, it was the custom of my tutor, Professor G.C. Berkouwer, to lecture on one doctrine per year. In 1965 he departed from his normal policy and lectured on “The History of Heresy in the Christian Church.”

Berkouwer canvassed the most important struggles the church faced against heresy. It was Marcion’s heretical canon that made it necessary for the church to formalize the contents of the true canon of sacred Scripture. It was Arius’s adoptionism that necessitated the conciliar decrees of Nicaea. It was the heresies of Eutyches (monophysitism) and Nestorius that provoked the watershed ecumenical council of Chalcedon in 451. The heresies of Sabellius, Apollinarius, the Socinians, and others have driven the church through the ages to define the limits of orthodoxy.

One of the major points in Berkouwer’s study was the historical tendency for heresies to beget other heresies, particularly heresies in the opposite direction. For example, efforts to defend the true humanity of Jesus often led to the denial of His deity. Zeal to defend the deity of Christ often led to a denial of His humanity. Likewise the zeal for the unity of the Godhead and monotheism have led to the denial of the personal distinctions in the being of God, whereas zeal for personal distinctives have led to tritheism and a denial of the essential unity of God. Likewise, efforts to correct the heresy of legalism have produced the antinomian heresy and vice versa.

We live in a climate where heresy is embraced and proclaimed with the greatest of ease. I can’t think of any of these major heresies that I haven’t heard repeatedly and openly on national tv by so-called “evangelical preachers” such as Hinn, Crouch, and the like. Where our fathers saw these issues as matters of life and death, indeed of eternal life and death, we have so surrendered to relativism and pluralism that we simply don’t care about serious doctrinal error. We prefer peace to truth and accuse the orthodox of being divisive when they call a heretic a heretic. It is the heretic who divides the church and disrupts the unity of the body of Christ.

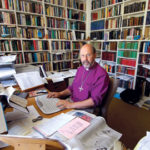

If you want a quick-but-tedious way to separate some of the shallower evanjellyfish from the more theologically-serious evangelicals in your circle of friends, here’s a simple method: call N.T. Wright a heretic. It’s quick because the blowback you will surely experience can be timed in microseconds. It’s tedious because you will be subjected to a series of overweeningly shrill diatribes, accompanied by confident insinuations that anyone who says such a thing is a divisive dolt. But a more effective method is difficult to find.

If you want a quick-but-tedious way to separate some of the shallower evanjellyfish from the more theologically-serious evangelicals in your circle of friends, here’s a simple method: call N.T. Wright a heretic. It’s quick because the blowback you will surely experience can be timed in microseconds. It’s tedious because you will be subjected to a series of overweeningly shrill diatribes, accompanied by confident insinuations that anyone who says such a thing is a divisive dolt. But a more effective method is difficult to find.