Here’s a 54 minute teaching I just recorded on the often misunderstood theme of “Free Will.”

Category Archives: Free Will

What About Free Will?

Chapter 6 of the book “Twelve What Abouts” by John Samson

Why are you reading this? Yes, this particular sentence. There are billions of sentences out there just waiting to be read, in many different languages. But right now, you are reading this one. Why?

Well, it could be that some Reformed and crazed individual has put a gun to your head and told you that if you did not read these words he would shoot you. He would definitely be what some refer to as a caged stage reformer: after coming to understand the doctrines of grace, for a period of a couple of years or so, he needs to be locked up in a cage. His zeal for Reformation truth needs to be augmented with sanity in human relations! He sends books, tapes, CD’s, mp3’s, DVD’s, and e-mails to all unsuspecting victims, regardless of whether or not they have ever shown an interest in these things. Christmas is his favorite time of the year, for he’s been eagerly waiting for this opportunity to send R. C. Sproul’s book “Chosen by God” to everyone he knows. He’s on a mission alright, but the best thing would be for him to cool down for a couple of years in a cage!

However, even with the crazed reformed nut with a gun scenario, you are still making the choice to read these words rather than face the contents of the gun. You prefer to read this rather than to feel the impact of the bullet. Even now, you are reading this because you want to – right now you do, anyway. In fact, because this is your strongest inclination, there is no possible way for you to be reading anything else at this moment. It is impossible that you would be reading something other than this right now, and this will continue to be the case until you have a stronger desire to do or to read something else.

So what exactly is free will? Do people have it? Does God have it? How free is God’s will? Can He do what He wants? Can we do what we want?

These kinds of questions are not new, of course. They have been the source of countless conversations and debates amongst ordinary folk and the chief theologians of the Church throughout history. Martin Luther, in looking back over his ministry considered his book on the subject of the will to be his most important work. In Luther’s mind, to misunderstand the will is to misunderstand the Reformation doctrine of sola gratia. He stated, If anyone ascribes salvation to the will, even in the least, he knows nothing of grace and has not understood Jesus Christ aright. (Luther, quoted by C.H. Spurgeon – New Park Street Pulpit, Sermon 52, Free will – a slave, Vol One, p. 395)

I don’t believe the issue is particularly complicated, which is why I am attempting to write a brief chapter on it here. This is not an entire treatise on the will. However, I think enough can be said in a short time to get all of us thinking. Continue reading

Does Man Have a Free Will?

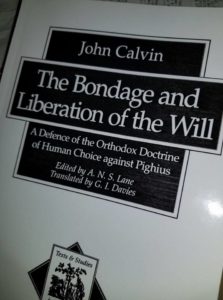

In his very helpful book, The Bondage and Liberation of the Will, John Calvin stated that there are four expressions regarding the will which differ from one another:

In his very helpful book, The Bondage and Liberation of the Will, John Calvin stated that there are four expressions regarding the will which differ from one another:

“namely that the will is free, bound, self-determined, or coerced. People generally understand a free will to be one which has in its power to choose good or evil …[But] There can be no such thing as a coerced will, since the two ideas are contradictory. But our responsibility as teachers is to say what it means, so that it may be understood what coercion is. Therefore we describe [as coerced] the will which does not incline this way or that of its own accord or by an internal movement of decision, but is forcibly driven by an external impulse. We say that it is self-determined when of itself it directs itself in the direction in which it is led, when it is not taken by force or dragged unwillingly. A bound will, finally, is one which because of its corruptness is held captive under the authority of its evil desires, so that it can choose nothing but evil, even if it does so of its own accord and gladly, without being driven by any external impulse.

According to these definitions we allow that man has choice and that it is self-determined, so that if he does anything evil, it should be imputed to him and to his own voluntary choosing. We do away with coercion and force, because this contradicts the nature of the will and cannot coexist with it. We deny that choice is free, because through man’s innate wickedness it is of necessity driven to what is evil and cannot seek anything but evil. And from this it is possible to deduce what a great difference there is between necessity and coercion. For we do not say that man is dragged unwillingly into sinning, but that because his will is corrupt he is held captive under the yoke of sin and therefore of necessity will in an evil way. For where there is bondage, there is necessity. But it makes a great difference whether the bondage is voluntary or coerced. We locate the necessity to sin precisely in corruption of the will, from which follows that it is self-determined.

(John Calvin, The Bondage and Liberation of the Will: A Defence of the Orthodox Doctrine of Human Choice against Pighius pp 69, 70)