Article source here.

Article source here.

The most famous evangelist of the nineteenth century declared that The Westminster Divines had created ‘a paper pope’ and had ‘elevated their confession and catechism to the Papal throne and into the place of the Holy Ghost.’ ‘It is better,’ he declared, ‘to have a living than a dead Pope,’ dismissing the Standards as casually as the boldest Enlightenment rationalist: ‘That the instrument framed by that assembly should in the nineteenth century be recognized as the standard of the church, or of any intelligent branch of it, is not only amazing, but I must say that it is highly ridiculous. It is as absurd in theology as it would be in any other branch of science.’1

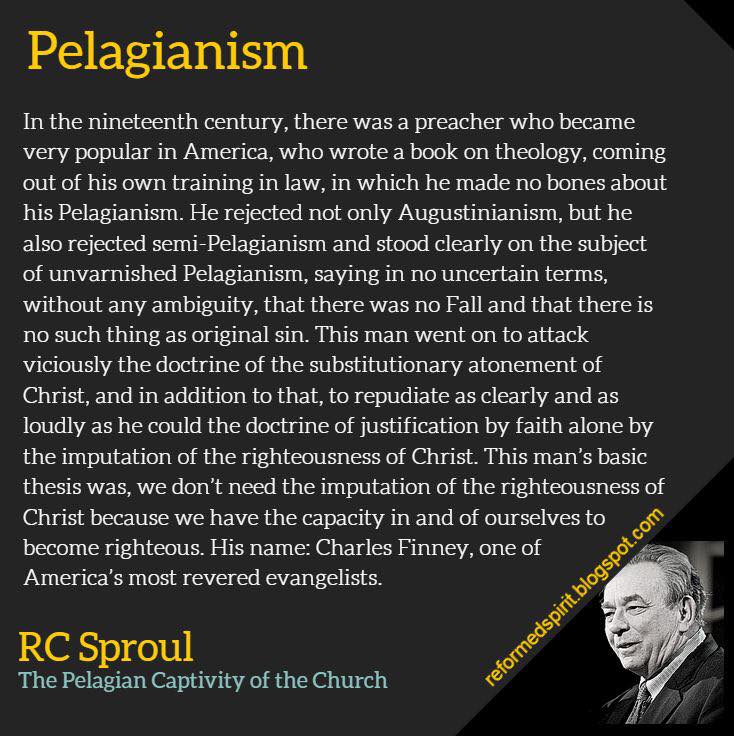

Given the unpopularity of Calvinism in particular and confessionalism in general, all of this might not have raised the slightest hint of impropriety except for the fact that the evangelist was Charles G. Finney, an ordained Presbyterian minister. In his introduction to Finney’s Lectures on Revivals of Religion, William McLoughlin wrote the following:

The first thing that strikes the reader of the Lectures on Revival is the virulence of Finney’s hostility toward traditional Calvinism and all it stood for. He denounced its doctrinal dogmas (which, as embodied in the Westminster Confession of Faith, he referred to elsewhere as ‘this wonderful theological fiction’); he rejected its concept of nature and the structure of the universe…; he scorned its pessimistic attitude toward human nature and progress…; and he thoroughly deplored its hierarchical and legalistic polity (as embodied in the ecclesiastical system of the Presbyterian Church). Or to put it more succinctly, John Calvin’s philosophy was theocentric and organic; Charles Finney’s was anthropocentric and individualistic….As one one prominent Calvinist editor wrote in 1838 of Finney’s revivals, ‘Who is not aware that the Church has been almost revolutionized within four or five years by means of such excitements?’

In this brief survey, our purpose will be two-fold: first, to understand the factors that shaped Finney’s theology and practice and, second, to appreciate the legacy of both for contemporary evangelicalism and especially Reformed faith and practice in the United States.

I. The Man: His Life & Times

We must remember that the period just prior to the Great Awakening was not congenial to an undiluted Calvinism: Jonathan Edwards lost his pulpit in 1750 in large part because he would not moderate his belief in total depravity; Solomon Stoddard, Edwards’ grandfather, had softened the Puritan emphasis on conversion in the interests of civil order with his ‘Half-Way Covenant,’ and the Enlightenment, having practically extinguished the remnants of orthodox Calvinism in English nonconformity, was threatening the citadels of American learning.

It was in reaction to the spiritual state of New England, ranging in general from nominal to skeptical, that a handfull of preachers–Anglican, Presbyterian, Congregationalist, and Dutch Reformed, but Calvinists all, began to recover the evangelical emphasis of the Protestant Reformers, summoning men and women to a confrontation with God through the Law and the Gospel. A cursory glance at the most popular sermon titles illustrates the dependence on classical biblical categories of sin and grace, judgment and justification, Law and Gospel, despair and hope, and these gifted evangelists were convinced that the success of their mission rested in the hands of God and faithfulness to the apostolic proclamation.

In spite of such biblical rigor, matched with evangelistic zeal, the Great Awakening (1739-43) itself was not without its excesses of enthusiastic religion, as Edwards himself was painfully aware. The Princeton divine labored to distinguish between true and false religious emotions. A man of towering presence and celebrated oratory, George Whitefield proved a valuable colleague in awakening sinners to God, and yet, as Harry S. Stout has argued in a controversial work, Whitefield himself may have contributed to some of the seminal features of mass evangelism that would manifest themselves in the revivalism to follow.2 The Tennent brothers, along with James Davenport, were also accused by some of their brethren as sowing seeds of unwholesome enthusiasm and a host of questions could be raised concerning the Awakening in terms of its ecclesiology and the prominence given to radical individual conversion over and against the more traditional covenantal motifs of Reformed theology. While the ‘New Light’ and ‘Old Light’ factions do not directly parallel the ‘New School’ and ‘Old School’ divisions to follow, they do reflect the controversial innovations introduced by those who sought to wed a pietistic impulse to Reformed orthodoxy, leading to a secession of Gilbert Tennent’s ‘New Light’ Presbyterians from the more traditional Philadelphia presbytery in 1741.

However essential it may be to raise those questions within the Reformed family, it is not within the scope of this brief survey to explore. It is sufficient for our purposes to at least recognize the fundamental Reformed consensus of the Great Awakening on anthropological and soteriological grounds. Revival was ‘a surprising work of God,’ as Edwards expressed it, and depended entirely on divine freedom.

The revivals associated with the Great Awakening created a rift in New England Congregationalism, encouraging many who were offended on grounds of taste and style (as well as the resurgent Calvinism) to embrace Unitarianism, while Edwards provided the intellectual resources for a courageous defense of Calvinism in conversation with, not merely in reaction to, the Enlightenment. Perhaps no other movement has had such a profound hand in shaping the religious character of Revolutionary America and the evangelicalism that is its heir–with the possible exception of the Second Great Awakening. Continue reading