Article by Jeff Robinson (original source here)

Article by Jeff Robinson (original source here)

Particular Baptist churches planted in the tumultuous soil of 17th century England grew up and bore fruit under a nasty set of doctrinal and methodological accusations, including that they subscribed to libertarian free will, denied original sin, that their pastors baptized women in the nude, and were opponents of church and crown.

Perhaps their most virulent and colorful opponent, Daniel Featley—a separatist persecutor deluxe—derisively dismissed our Baptist forebears, writing in a venom-filled pamphlet, “They pollute our rivers with their filthy washings.” Such was Baptist life under Charles I.

These nefarious charges and numerous others arose from leaders of the state church and led to decades of grinding persecution for Baptists. Seven churches returned fire, but not by brandishing the sword of steel or by hurling theological invectives. The seven carried out their war for truth by wielding the sword of the Spirit. The product was the most comprehensive expression of orthodox Baptist theology ever written—the Second London Confession of 1689.

The signers of that venerable confession lived and moved in an age in which most local congregations wrote confessions of faith for a number of reasons, one of them to demonstrate their commitment to the historic Christian faith. Additionally, they sought to manifest their solidarity with the prevailing forms of Calvinistic orthodoxy as well as to expound the basic elements of their ecclesiology. The Second London Confession also aimed at refuting popular notions associating Particular Baptists with the radical wing of the Anabaptist movement on the continent.

Of primary importance, they saw biblical warrant for the practice of confessionalism in texts such as 1 Timothy 3:16, where the apostle Paul’s inspired pen produced a brief but beautiful display of the mystery of godliness:

Great indeed, we confess, is the mystery of godliness: He was manifested in the flesh, vindicated by the Spirit, seen by angels, proclaimed among the nations, believed on in the world, taken up in glory.

Fast-forward to 2016 and many Baptist churches continue to have statements of faith “on the books” as a part of their foundational documents. Yet, I’ve found that many churches do not know how useful the confession can be beyond establishing subscription to certain core doctrines. This raises a fundamental question: How should a local church use their confession of faith? Here are six ways a church might use a confession of faith. I owe at least four of these to my friend Sam Waldron’s fine work, A Modern Exposition of the 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith (Evangelical Press). Confessions of faith should be used:

1. As an affirmation and defense of the truth. The church of the living God is called to be the pillar and buttress of the truth (1 Tim. 3:15). It is to “follow the pattern of sound words” (2 Tim. 1:13) and to “earnestly contend for the faith once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 3). Insofar as a confession reflects the Word of God, it is useful for helping the church discern truth from error. Many of the great confessions in church history have affirmed biblical truths while simultaneously condemning unbiblical expressions of the same. Paul called Timothy to guard the good deposit entrusted to him (2 Tim. 1:14), and likewise, faithful Christians are called to keep a close watch over it. A part of this stewardship is clearly articulating the truth and defending it in the face of error. A more recent example of this is the Baptist Faith & Message 2000. Southern Baptists, rightly, revised their confession, adding article XVIII to address areas where feminism had begun to encroach on the church and Christian family.

2. As a baseline for church discipline. In 1 Timothy 5:16, Paul famously admonished Timothy to “Keep a close watch on yourself and on the teaching. Persist in this, for by so doing you will save both yourself and your hearers.” As a matter of stewardship, church purity, and love to neighbor, a faithful pastor, a faithful elder board, a faithful church member must keep a close eye on the life and doctrine of those within their congregation. Church discipline (Matt. 18:15-18) is a key part of this. The confession of faith forms the baseline for determining whether or not a church leader or member has strayed from orthodox belief or orthodox living. It provides an objective standard for both accusation and restoration in church discipline.

Andrew Fuller wrote of the care that must be taken in church discipline and the role of the confession if that pursuit:

“If a religious community agrees to specify some leading principles which they consider as derived from the Word of God, and judge the belief of them to be necessary in order to any person’s becoming or continuing a member with them, it does not follow that those principles should be equally understood, or that all their brethren must have the same degree of knowledge, nor yet that they should understand and believe nothing else. The powers and capacities of different persons are various; one may comprehend more of the same truth than another, and have his views more enlarged by an exceedingly great variety of kindred ideas; and yet the substance of their belief may still be the same. The object of the articles is to keep at a distance, not those who are weak in the faith, but such as are his avowed enemies.”

3. As a means of theological triage and Christian maturity. Which doctrines must be believed for one to be considered a genuine follower of Christ? Which doctrines represent denominational distinctives? Which doctrines are tertiary and may be relegated to the category of “good men disagree?” A solid and effective local church confession takes an unambiguous stand on doctrines that should mark the genuine Christian. It also rings clear on denominational distinctives. But a wise and well-articulated church confession also avoids unnecessary sectarianism by refusing to take a hard line on so-called “third-tier” issues such as the timing of Christ’s return, specific details of the millennium, preferred English Bible translations, and those similar.

4. As a concise standard by which to evaluate ministers of the Word. The apostle Paul told Timothy to entrust the great truths of God to faithful men (2 Tim. 2:2). Faithful men are faithful to sound doctrine, faithful to the Scriptures. When calling a new pastor or a new elder, the church’s confession provides the doctrinal standard by which his fitness is to be judged. It also provides a crucial baseline by which to measure his theological solidarity—or lack thereof—with the body that is considering him for ministry.

5. As a doctrinal basis for planting daughter churches. Churches typically speak of potential offspring as “having our DNA.” A confession of faith establishes a key part of the genetic structure that is to be passed on. As a historical example, the Charleston Association used a slightly revised version of the Philadelphia Confession as the doctrinal standard for church plants across the Southeast. My family remains involved in church in north Georgia planted by Charleston under the Philadelphia Confession in 1832.

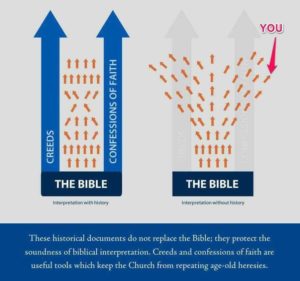

6. As a means of establishing historical continuity and unity with other Christians. The framers of the Second London Confession aimed to show that Particular Baptists were not given to theological novelties, but stood with two feet firmly planted in the historic Christian tradition. They subscribed to the Trinitarianism of the early creeds, the Christology of Chalcedon, the five solas of the Reformation, and much more that comprises evangelical orthodoxy. Local churches do the same when they proclaim where they stand on these core theological doctrines.

A healthy church is one that knows what it believes, preaches what it believes, teaches what it believes, sings what it believes, prays what it believes, confesses what it believes, and seeks, by God’s enabling grace, to live what it believes. In other words, a healthy church is a confessional church.

Article: John Gill, the rule of faith and baptist catholicity by David Rathel (original source

Article: John Gill, the rule of faith and baptist catholicity by David Rathel (original source  Article by by Carl R. Trueman (original source

Article by by Carl R. Trueman (original source