The value of creeds and confessions in the life of the believer and the church.

Category Archives: Creeds

The Athanasian Creed

Quicumque vult – this phrase is the title attributed to what is popularly known as the Athanasian Creed. It was often called the Athanasian Creed because for centuries people attributed its authorship to Athanasius, the great champion of Trinitarian orthodoxy during the crisis of the heresy of Arianism that erupted in the fourth century. That theological crisis focused on the nature of Christ and culminated in the Nicene Creed in 325. Though Athanasius did not write the Nicene Creed, he was its chief champion against the heretics who followed after Arius, who argued that Christ was an exalted creature but that He was less than God.

Athanasius died in 373 AD, and the epithet that appeared on his tombstone is now famous, as it captures the essence of his life and ministry. It read simply, “Athanasius contra mundum,” that is, “Athanasius against the world.” This great Christian leader suffered several exiles during the embittered Arian controversy because of the steadfast profession of faith he maintained in Trinitarian orthodoxy.

Though the name “Athanasius” was given to the creed over the centuries, modern scholars are convinced that the Athanasian Creed was written after the death of Athanasius. Certainly, Athanasius’ theological influence is embedded in the creed, but in all likelihood he was not its author.

The content of the Athanasian Creed stresses the affirmation of the Trinity in which all members of the Godhead are considered uncreated and co-eternal and of the same substance. In the affirmation of the Trinity the dual nature of Christ is given central importance. As the Athanasian Creed in one sense reaffirms the doctrines of the Trinity set forth in the fourth century at Nicea, in like manner the strong affirmations of the fifth-century council at Chalcedon in 451 are also recapitulated therein. As the church fought with the Arian heresy in the fourth century, the fifth century brought forth the heresies of monophysitism, which reduced the person of Christ to one nature, mono physis, a single theanthropic (God-man) nature that was neither purely divine or purely human. At the same time the church battled with the monophysite heresy, she also fought against the opposite view of Nestorianism, which sought not so much to blur and mix the two natures but to separate them, coming to the conclusion that Jesus had two natures and was therefore two persons, one human and one divine. Both the Monophysite heresy and the Nestorian heresy were clearly condemned at the Council of Chalcedon in 451, where the church, reaffirming its Trinitarian orthodoxy, stated their belief that Christ, or the second person of the Trinity was vere homo and vere Deus, truly human and truly God. It further declared that the two natures in their perfect unity coexisted in such a manner as to be without mixture, confusion, separation, or division, wherein each nature retained its own attributes.

The Athanasian Creed reaffirms the distinctions found at Chalcedon, where in the Athanasian statement Christ is called, “perfect God and perfect man.” All three members of the Trinity are deemed to be uncreated and therefore co-eternal. Also following earlier affirmations, the Holy Spirit is declared to have proceeded both from the Father “and the Son.”

Finally, the Athanasian standards examined the incarnation of Jesus and affirmed that in the mystery of the incarnation the divine nature did not mutate or change into a human nature, but rather the immutable divine nature took upon itself a human nature. That is, in the incarnation there was an assumption by the divine nature of a human nature and not the mutation of the divine nature into a human nature.

The Athanasian Creed is considered one of the four authoritative creeds of the Roman Catholic Church, and again, it states in terse terms what is necessary to believe in order to be saved. Though the Athanasian Creed does not get as much publicity in Protestant churches, the orthodox doctrines of the Trinity and the incarnation are affirmed by virtually every historic Protestant church.

Confessions

In an article entitled “The Value of Confessions” in Douglas F. Kelly writes:

In an article entitled “The Value of Confessions” in Douglas F. Kelly writes:

To this day, Christian Churches, especially in the Reformation tradition, use a powerful tool for “maintaining the form of sound words” and for spreading the gospel to the world—their confessional documents. The Protestant Reformation of the sixteenth century represented a major rupture in the medieval church, one in which more than one-third of Europe had to go back to the “drawing board” to formulate their testimony to the rest of the world.

That drawing board was Holy Scripture, which consecrated pastor-scholars searched out on the basis of a fresh knowledge of the original languages, and also on the basis of a commitment to traditional Augustinianism and the church fathers. Hence, they saw themselves as true (or Reformed) catholics, not primarily a new denominational grouping, although they did wind up in new denominational connections owing to the fierce resistance of the Roman Catholic hierarchy to any serious reform.

It was necessary to define themselves in light of Roman Catholic charges that they had left the true church and were following heretical teachings. They carried out this task as churches with careful and prayerful exegetical work through the entirety of Scripture in order to state coherently the major lines of its teaching on both doctrine and duty. Several synods in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries fulfilled this task with solid grounding on the Word of God written and in line with the traditional creeds of the first five centuries of Christian history.

The results of their work were developed over time (from the first Reformed confessions in the 1520s and 1530s to the Westminster Confession of Faith in the 1640s). These standards solidly appealed to the clear teaching of Holy Scripture. The Bible was their touchstone. Indeed, the framers of the Scots Confession of 1560 stated that if anyone could show them that they were out of accord with Scripture, they would be willing to change. While always respecting the historical church, they clearly stated that Scripture must have the final word, for, in the words of the Westminster Confession, “The purest churches under heaven are subject both to mixture and error” (25.5).

Out of this crucible of controversy came several confessions that, with general brevity and clarity, express the main thrust of the teachings of Holy Scripture on salvation and holy living. Because of their biblical teaching, they have the value of guiding us as much today as they did our forefathers centuries ago. It is a mercy for the church today not to have to reinvent the wheel. Through the creeds and confessions, we abide in the health and safety of “the communion of the saints.”

This doctrinal continuity runs contrary to the relativism of our Western secularized culture, according to which “ancient truth is uncouth.” This relativism suggests that instead of ancient truth, one must feverishly follow the latest fads of the ever-changing intelligentsia. Furthermore, the aggressive relativism of our culture has not stopped at the doors of the church. To refer appreciatively to the confessional standards causes the raising of eyebrows, and, in some cases, open protest in not a few evangelical (and Reformed) congregations and denominations.

Many evangelicals, in order to avoid the clear teachings of these confessions (which are based on the supernatural claims of the Bible) and not offend the reigning relativism of our culture (which, at the end of the day, is anti-supernatural), employ a sort of “nominalistic” interpretation of the standards. A “nominalistic” interpretation means avoiding the plain teaching of these biblically based confessions by formally subscribing to them while employing clever and painful endeavors to make them say something else; something that will be less offensive to the secular culture.

One instance is how theistic evolutionists engage in a sort of “Jesuit casuistry” to force the first three chapters of Genesis to say precisely what they preclude—that there was sin before the fall of Adam and that life gradually developed by chance.

A great value of the Westminster Confession’s teaching on creation, for example, is that in following it, we are not prey to changing paradigms of philosophical science (which is not the same thing as empirical or operational science, which, in my view, is fully compatible with the teachings of Genesis). Here the standards can help us greatly (if we abide in them realistically, rather than nominalistically evading their meaning): they plainly tell the church what the Bible has always said on creation rather than leading us on a wild goose chase of post-Enlightenment philosophies. They help the church to see that approaches such as theistic evolution come not from the Bible but from somewhere else, and need to be identified as such. Their valuable testimony helps us to continue to stand on a solid biblical foundation, which, though offensive to the secular world, is the place where we find intellectual coherence of truth in the context of Word and Spirit, which is life-giving and transformational for all of thought and culture.

– Dr. Douglas F. Kelly is Richard Jordan Professor of Theology at Reformed Theological Seminary in Charlotte, North Carolina. He is author of Revelation: A Mentor Expository Commentary.

Sola Scriptura and the Reformed Confessions

The Martin Luther was already in hot water with the pope after having posted his Ninety-Five Theses the previous year. But he made things considerably worse for himself when, in a debate with Dominican Cardinal Cajetan, he asserted that the pope could and had erred. He turned up the heat considerably in the summer of 1519 when he confessed to Johannes von Eck that not only could popes and councils err, they had erred grievously in condemning John Huss.

The Martin Luther was already in hot water with the pope after having posted his Ninety-Five Theses the previous year. But he made things considerably worse for himself when, in a debate with Dominican Cardinal Cajetan, he asserted that the pope could and had erred. He turned up the heat considerably in the summer of 1519 when he confessed to Johannes von Eck that not only could popes and councils err, they had erred grievously in condemning John Huss.

So was born the Protestant doctrine of sola Scriptura. It was not that Luther despised church authority. He merely recognized that Scripture alone was inerrant and infallible, and therefore only Scripture possessed absolute normative authority. This principle is codified in several sixteenth century Reformed confessions which R. C. Sproul excerpts in the first chapter of his book, Scripture Alone.

The Theses of Berne (1528):

The church of Christ makes no laws or commandments without God’s Word. Hence all human traditions, which are called ecclesiastical commandments, are binding upon us only in so far as they are based and commanded by God’s Word. (Sec. 2)

The Geneva Confession (1536):

First we affirm that we desire to follow Scripture alone as a rule of faith and religion, without mixing it with any other things which might be devised by the opinion of men apart from the Word of God, and without wishing to accept for our spiritual government any other doctrine than what is conveyed to us by the same Word of God, and without addition or diminution, according to the command of our Lord. (Sec. 1)

The French Confession of Faith (1559):

We believe that the Word contained in these books has proceeded from God, and receives itls authority from God alone, and not from men. And inasmuch as is the rule of all truth, containing all that is necessary for the service of God and for our salvation it is not lawful for men, even for angels, to add to it, to take away from it, or to change it. Whence it follows that no authority whether of antiquity, or custom or numbers, or human wisdom, or judgments, or proclamations, or edicts, or decrees, or councils or visions, or miracles, should be opposed to these holy Scriptures, but on the contrary, all things should be examined, regulated and reformed according to them. (Art. 5)

The Belgic Confession (1561):

We receive all these books, and these only as holy and confirmation of our faith; believing, without any doubt, all things contained in them, not so much because the church receives, and approves them as such, but more especially because the Holy Ghost witnessed in our hearts that they are from God, whereof they carry the evidence in themselves (Art. 5).

Therefore we reject with all our hearts whatsoever doth not agree with this infallible rule (Art. 7).

The Second Helvic Confession (1566):

Therefore, we do not admit any other judge that Christ himself, who proclaims by the Holy Scriptures what is true, what is false, what is to be followed, or what is to be avoided (chap. 2).

— R. C. Sproul, Scripture Alone (P&R Publishing Company, 2005), 18–20.

A Cult or a False Church?

Is the Coptic Orthodox Church a cult?

Is the Coptic Orthodox Church a cult?

This is a Reformed Blog and so obviously, you will find a Reformed position outlined here. In Evangelical and Reformed circles historically, the word “cult” has denoted groups, organizations and churches that deny the catholic (or universal) creeds of the church concerning the full humanity and deity of Jesus Christ and the Holy Trinity – there is one God, eternally existent in three Divine Persons who are co-equal and co-eternal; Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

The Protestant Reformers would not use the word “cult” to refer to the Roman Catholic Church because unlike the Mormons, Jehovah’s Witnesses and groups like them, the RCC does indeed affirm orthodox doctrine on the essentials mentioned above.

However, it must be said that no true Christianity can exist without the Gospel. The entire New Testament book of Galatians affirms this. Therefore, despite their orthodoxy on the doctrine of God and of our Lord Jesus Christ, the Reformers would declare Rome to be a “false church” because of its strong denial and pronouncement of an anathema (eternal curse) on anyone who believes sola fide (justification by faith alone), which is of course, the very heart of the gospel of grace – justification being “the article upon which the church stands or falls” (Luther).

Let me therefore answer your question with a question – what is the official position of the Coptic Orthodox Church concerning the doctrines of the full humanity and full deity of Christ, the Trinity and justification by faith alone? Answer this clearly from their official documents, affirmations and declarations and you will have your answer. More than that, what is true concerning the Coptic Orthodox Church is true for any group or Church?

Comparing the Confessions

For those who would like to examine the differences between the 1646 Westminster Confession of Faith and the 1689 London Baptist Confession of Faith, a very helpful tabular comparison can be found at this link.

For those who would like to examine the differences between the 1646 Westminster Confession of Faith and the 1689 London Baptist Confession of Faith, a very helpful tabular comparison can be found at this link.

The Reformed Faith

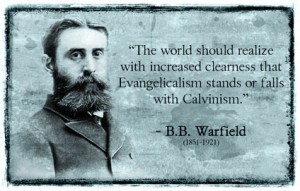

A Brief and Untechnical Statement of the Reformed Faith by Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield

A Brief and Untechnical Statement of the Reformed Faith by Benjamin Breckinridge Warfield

1. I believe that my one aim in life and death should be to glorify God and enjoy him forever; and that God teaches me how to glorify him in his holy Word, that is, the Bible, which he had given by the infallible inspiration of this Holy Spirit in order that I may certainly know what I am to believe concerning him and what duty he requires of me.

2. I believe that God is a Spirit, infinite, eternal and incomparable in all that he is; one God but three persons, the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost, my Creator, my Redeemer, and my Sanctifier; in whose power and wisdom, righteousness, goodness and truth I may safely put my trust.

3. I believe that the heavens and the earth, and all that in them is, are the work of God’s hands; and that all that he has made he directs and governs in all their actions; so that they fulfill the end for which they were created, and I who trust in him shall not be put to shame but may rest securely in the protection of his almighty love.

4. I believe that God created man after his own image, in knowledge, righteousness and holiness, and entered into a covenant of life with him upon the sole condition of the obedience that was his due: so that it was by willfully sinning against God that man fell into the sin and misery in which I have been born.

5. I believe, that, being fallen in Adam, my first father, I am by nature a child of wrath, under the condemnation of God and corrupted in body and soul, prone to evil and liable to eternal death; from which dreadful state I cannot be delivered save through the unmerited grace of God my Savior.

Continue reading

Creeds I Affirm

When people ask me what historic Christian creeds I affirm I say:

When people ask me what historic Christian creeds I affirm I say:

(1) The Apostles’ Creed

(2) The Nicene Creed

(3) The Athanasian Creed

(4) The Chalcedonian Creed

(5) The London Baptist Confession of Faith of 1689, which in modern English can be found here.

What to Do with Creeds and Councils?

By John Starke:

By John Starke:

The church—be it Catholic, Orthodox, or Protestant—has long debated the role of creeds and councils without reaching full consensus. Evangelicals care about sound doctrine, and we would be wrong to think it didn’t exist until the Reformation. So what’s an appropriate emphasis on creeds and councils for evangelicals in particular? What authority should they have in our life and doctrine?

Follow Me as I Follow Christ

In his first letter to the Corinthians, after exhorting them to do all things for the glory of God (10:23-33), Paul sets himself apart as an example when he says, “Follow me as I follow Christ” (1 Cor. 11:1). Notice, though, he doesn’t set himself apart as a perfect guide. He has a very important qualification: “as I follow Christ.” In other words, Paul wants his readers to recognize where Paul’s life is that of Christ’s (I would say, where it is biblical) and therefore follow him in that way. This is an easy paradigm to remember how Protestants have thought about creeds and councils: follow the creeds and councils as they follow the Bible.

Bruce Demarest, in an older Themelios article, “The Contemporary Relevance of Christendom’s Creeds” (by the way, you can look through our entire archives of Themelios, all the way back to 1975) makes the same point rather well:

The creed is not only a rule; it is also a rule that is ruled. As human formulations the creeds are subordinate to Scripture, the supreme rule of faith and practice. However majestic its language, however moving its assertions, however closely it purports to approximate apostolic doctrine, the creed is a human and therefore potentially fallible document. Ultimately the creeds must be checked and ruled by the Word of God. Christendom’s creeds are worthy of honour to the degree that they accord with the teaching of the Word of God.

What Kind of Authority

Since we’ve concluded that the creeds and councils don’t have ultimate authority, which is ascribed only to Scripture, do they have any authority at all? There’s a cavalier spirit in evangelicals that is quick to say, No! But that’s a tough line to plow since our evangelical understanding of the gospel is built upon the orthodox formulations of the creeds and councils. Even the most rogue, “no-creed-but-the-Bible” evangelical still uses words like orthodox and heresy. These aren’t biblical words, so to speak, but Christian words that depend upon some sort of agreement as to what our spiritual ancestors have claimed to be good and right beliefs and what is damnable, according to the Bible.

Continue reading

The Importance of the Creeds

“To say that “a creed comes between a man and his God” is to suppose that which is not true; for truth, however definitely stated, that which I believe I am not ashamed to state in the plainest possible language; and the truth I hold I embrace because I believe it to be the mind of God revealed in his infallible Word. How can it divide me from God who revealed it? It is one means of my communion with my Lord, that I receive his words as well as himself, and submit my understanding to what I see to be taught by him. Say what he may, I accept it because he says it, and therein pay him the humble worship of my inmost soul.

“To say that “a creed comes between a man and his God” is to suppose that which is not true; for truth, however definitely stated, that which I believe I am not ashamed to state in the plainest possible language; and the truth I hold I embrace because I believe it to be the mind of God revealed in his infallible Word. How can it divide me from God who revealed it? It is one means of my communion with my Lord, that I receive his words as well as himself, and submit my understanding to what I see to be taught by him. Say what he may, I accept it because he says it, and therein pay him the humble worship of my inmost soul.

I am unable to sympathize with a man who says he has no creed; because I believe him to be in the wrong by his own showing. He ought to have a creed. What is equally certain, he has a creed—he must have one, even though he repudiates the notion. His very unbelief is, in a sense, a creed.” – C. H. Spurgeon, from an article titled “The Baptist Union Censure,” published as an introduction to the 1888 volume of The Metropolitan Tabernacle Pulpit sermons

“Doctrine divides!” That’s the popular belief of our culture today, as its sails on the shifting sea of modern day relativism. Our generation shouts out, “It doesn’t matter what you believe, as long as you are sincere,” yet the Bible portrays a very different message.

“Doctrine divides!” That’s the popular belief of our culture today, as its sails on the shifting sea of modern day relativism. Our generation shouts out, “It doesn’t matter what you believe, as long as you are sincere,” yet the Bible portrays a very different message.

We have to admit that doctrine does in fact divide. It divides truth from error, the true prophet from the false prophet, and the real Christ from the counterfeit.

In another sense though, doctrine unites. It allows those who hold to the truth of Scripture to come together under the banner of that truth.

In this ocean of change, there stands a bedrock that has stood the test of time. It is an ancient creed that offers a sure and safe haven, and is an anchor in a theological world adrift and deceived. Christians throughout the centuries have built their lives on it, believing that its statements are merely reflections of what the Bible teaches about God, His Son, Jesus Christ, and the life the Holy Spirit brings to His Church.

The Apostles’ Creed portrays the very heart of the Christian faith the core teachings that are dispensed with only at great peril to the soul. It is the theological and orthodox “bottom line” concerning what we as Christians believe, and it dates from very early times in the Church, a half century or so from the last writings of the New Testament.

THE APOSTLES’ CREED

I believe in God, the Father Almighty, the Creator of heaven and earth and in Jesus Christ, His only Son, our Lord:

Who was conceived of the Holy Spirit, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, died, and was buried.

He descended into hell.

The third day He arose again from the dead.

He ascended into heaven and sits at the right hand of God the Father Almighty, whence He shall come to judge the living and the dead.

I believe in the Holy Spirit, the holy *catholic church, the communion of saints, the forgiveness of sins, the resurrection of the body, and life everlasting. Amen.

* The word “catholic” refers not so much to the Roman Catholic Church, but to the universal church of the Lord Jesus Christ.

In a similar way, the Nicene creed has helped even further to define what the Scriptures teach.

THE NICENE CREED

I believe in one God, the Father Almighty, Maker of heaven and earth, and of all things visible and invisible.

And in one Lord Jesus Christ, the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds; God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God; begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father, by whom all things were made.

Who, for us men for our salvation, came down from heaven, and was incarnate by the Holy Spirit of the virgin Mary, and was made man; and was crucified also for us under Pontius Pilate; He suffered and was buried; and the third day He rose again, according to the Scriptures; and ascended into heaven, and sits on the right hand of the Father; and He shall come again, with glory, to judge the quick and the dead; whose kingdom shall have no end.

And I believe in the Holy Ghost, the Lord and Giver of Life; who proceeds from the Father and the Son; who with the Father and the Son together is worshipped and glorified; who spoke by the prophets.

And I believe one holy catholic and apostolic Church. I acknowledge one baptism for the remission of sins; and I look for the resurrection of the dead, and the life of the world to come. Amen.

Then a third creed, known as the Athanasian creed, named after Athanasias, was developed as a standard for Christian belief. Continue reading