Article by Tom Hicks – original source here.

With Christianity on the wane in Western culture, some leaders have urged Christians to deemphasize secondary doctrines in order to stand united on gospel essentials. Our numbers are too small, they say, for Christians to continue nit picking at each other on long disputed matters of theology. Let me suggest, however, that doctrinal minimalism is the wrong approach, especially at this time. While all true Christians should stand united for the advancement of Christ’s kingdom and against the rising specter of secularism, this is not the time to sideline secondary doctrines of the faith. Now, more than ever, we need robust, thoroughly biblical expressions of Christianity. We need an encyclopedically confessional faith.

Consider briefly three reasons this is true. First, when Christianity was small and under pressure in Rome, the apostle Paul wrote the church of Rome a detailed theological letter that included carefully articulated secondary doctrines. Paul believed that rich theology is needed for healthy Christians and churches during troubled times. Second, because the culture continues to assault the gospel, we need the Bible’s whole theological support structure, if the gospel is to remain intact. Secondary doctrines provide the necessary intellectual and ecclesiastical supports of the gospel. Third, when the surrounding culture is most decidedly opposed to the faith, evangelism and disciple making must be theologically robust, if conversions are to be sound, since converts will be coming from worldviews that are radically different from that of Scripture. These converts will also need well-developed theologies to think and live Christianly in our post-Christian society.

It is with these thoughts in mind that I offer the following review of Carl Trueman’s book, the Creedal Imperative. Trueman’s work summons the churches, particularly the churches of the Protestant and Reformed tradition, to embrace thoroughgoing creedalism. This delightful volume is well-written, witty, historically precise, and deeply applicable to our contemporary situation. While Trueman’s book is full of cultural commentary, historical perspective and theological discussion, here are some of his arguments for creedalism that I found most helpful.

1. Creedalism confronts our culture’s suspicion about words. We live in a culture in which pictures, feelings, and sound bites are often believed to convey more meaning than carefully crafted words. Our postmodern age doubts whether words can carry objective meaning. But God chose to reveal Himself by the inscripturated words of the Bible. Like the Bible, confessions of faith convey God’s truth through words. Creeds insist that words are suitable vehicles for the communication of objective truth.

2. Creedalism confronts our culture’s anti-historical bent. Because Western culture is so deeply influenced by evolution, it’s reluctant to value the wisdom of ages past. Westerners believe that new ideas are better than old ones. But creedalism asserts that true wisdom is as old as God’s own mind and that the sages of the past have more to offer than the innovators of the present. Another reason for Western culture’s anti-historicism has to do with the fact that Westerners don’t view human nature as constant across time. What does someone in the 17th Century have in common with me? But Scripture teaches that human beings have the same fallen nature across time and that the same old gospel reconciles us to God.

3. Creedalism confronts our culture’s anti-institutionalism. Western society is basically anti-authoritarian and therefore distrusts all institutions, including the institution of the church. Our society tends to trust, not those who are actually skilled and knowledgable to speak to important issues, but those who are young and popular, like Lady Gaga. But the Bible clearly declares that the church is a “pillar and buttress of truth” (1 Tim 3:15), and that it supports the truth by way of confession: “great indeed we confess is the mystery of godliness” (1 Tim 3:16). God calls pastors and churches to teach the whole counsel of God and enforce orthodoxy by way of their God given authority under Christ and His Word.

4. Creedalism is required by the Bible. In 2 Timothy 1:13-14, Paul says, “Follow the pattern of the sound words that you have heard from me, in the faith and love that are in Christ Jesus. By the Holy Spirit who dwells within us, guard the good deposit entrusted to you.” Commenting on these verses, Carl Trueman writes, “Conspicuously, Paul does not simply say to Timothy, ‘Memorize the Old Testament or the Gospels or my Letters’ any more than he ever defines preaching as the reading of the same. The form [pattern] of sound words is something more [that is: a pattern of words that explains the content of Scripture, as in creeds]. Anyone who claims to take the Bible seriously must take the words of Paul to Timothy on this matter seriously. To claim to have no creed but the Bible, then, is problematic: the Bible itself seems to demand that we have forms of sound words, and that’s what creeds are” (75-76).

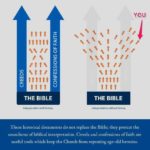

5. Creedalism prevents innovative and inferior theological formulations. Some pastors and teachers, who call themselves “biblicists,” approach the Bible independently and innovatively without consulting the careful work of historical theology. They do this, even though teachers and pastors have been hard at work formulating doctrine, throughout the history of the church, so that the full meaning of Scripture is clear while errors are avoided and excluded. Trueman wisely warns the “biblicist” pastor, “Do not precipitately abandon creedal formulations which have been tried and tested over the centuries by churches all over the world in favor of your own ideas. On the whole, those who reinvent the wheel invest a lot of time either to come up with something that looks identical to the old design or something that is actually inferior to it. This is not to demand capitulation before church tradition or a rejection of the notion of Scripture alone. Rather, it is to suggest an attitude of humility toward the church’s past which simply looks both at the good that the ancient creeds have done and also the fact that they seem to make better sense of the testimony of Scripture than any of the alternatives” (107).

6. Creedalism alone allows for the most open critique of theology. Those who claim to have “no creed but the Bible” actually do have a creed. They have an opinion about what the Bible teaches on doctrines such as predestination, the will of man, assurance, baptism, the nature of the church, etc. The only difference between someone who claims “no creed but the Bible” and a “creedalist” is that the creedalist writes his creed down so that it can be examined and critiqued by Scripture. Trueman writes, “What he [the non-creedalist] really should have said was: I have a creed but I am not going to write it down, so you cannot critique it; and I am going to identify my creed so closely with the Bible that I am not going to be able to critique it either” (160).

7. Creedalism avoids authoritarianism. According to Trueman, non-creedalist “biblicists” are actually “more authoritarian than the papacy” (161). Since non-creedalist pastors and teachers will not write down what they believe so that their beliefs can be critiqued, they may teach their churches whatever they personally come to believe the Bible says even if that changes over time. For non-creedal teachers, primary authority is located in their own personal interpretation, rather than in the church’s written and agreed upon creedal interpretation, which is open to public scrutiny.

8. Creedalism is in the best position to guard the supreme authority of Scripture. Orthodox creeds assert the Scripture’s supreme authority, which protects the church from elevating a creed to the level of Scripture. Anyone who attempted to give the creed more authority than Scripture could be corrected both by the Scripture and by the creed itself. Moreover, “once the creed or confession is in the public domain, mechanisms can be put in place to allow for it to function in a subordinate role to Scripture” (161).

9. Creedalism is a biblical basis of congregational worship. Because creeds are concise and careful summaries of biblical teaching, they are foundational to worship. A church must be accurately instructed about the nature of God and His works in order to praise Him properly. Trueman writes, “The identity of God has priority over the content of Christian praise” (143). A congregation that knows an orthodox creed is well-equipped for praise. Creeds may also be recited and sung in corporate worship services.

Article by Jeff Robinson (original source here)

Article by Jeff Robinson (original source here)