Article: Why There is No Such Thing as the Gift of Tongues by Eric Davis, pastor of Cornerstone Church in Jackson Hole, WY. (original source here)

Article: Why There is No Such Thing as the Gift of Tongues by Eric Davis, pastor of Cornerstone Church in Jackson Hole, WY. (original source here)

From time to time pastors are asked about a phenomena common to Christianity in the past one hundred years called “the gift of tongues.” The phrase generally refers to a spectrum of experiences, ranging from a supposed private, non-earthly prayer language spoken between the believer and God enabled by the Holy Spirit, to an angelic, non-earthly prayer language by the believer in prayer and worship, to an ecstatic non-earthly utterance enabled by the Spirit spontaneously in the believer in private and/or public worship.

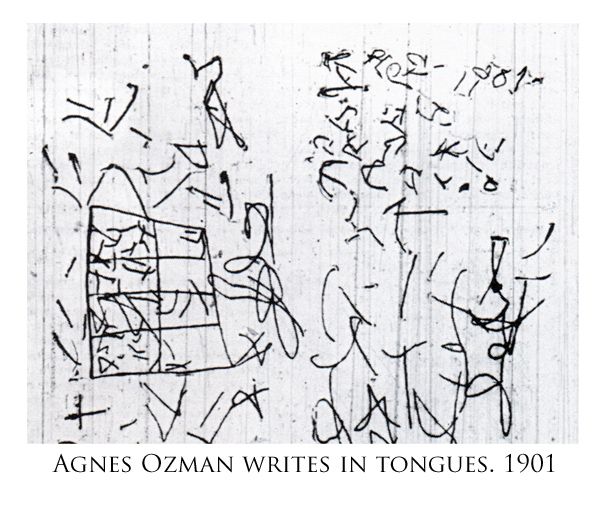

Understandably, the phenomena has created much excitement and inquiry since its rise in the early 1900’s. Professing Christians who experience the phenomena often testify to things such as the encouraging feeling it brings, comfort in the Christian life, and joy. Notwithstanding these, and many other experiences, God’s people must evaluate all things claimed to be of God by proper interpretation of Scripture. When done so, it becomes apparent that this phenomena cannot be justified from the word of God. Having said that, Scripture does teach that there existed a miraculous gift of languages during the foundational, apostolic era of the New Testament church. As clear from Scripture, this was the miraculous ability to speak an unlearned language that is known by others on earth for the purpose of exalting Christ and building up others, while pronouncing judgment on Israel. This was a critical gift for laying the foundation of the church, and, as such, has ceased. However, phenomena as previously mentioned and beyond the biblical gift of languages cannot be justified from Scripture. Briefly, here are eleven reasons why there is no gift of tongues.

The meaning of the word “tongues.”

“Tongues” is an unfortunate rendering of the Greek word γλῶσσα. The word refers either to the tongue organ or spoken human languages understood by other people groups on Earth. Thus, references both in Acts and 1 Corinthians 12-14 refer, not to a private prayer phenomena, but a gift of languages, involving human earthly languages.

The definition of New Testament spiritual gifts.

In 1 Corinthians 12-14, the gift of “tongues,” or “languages,” is referred to as a spiritual gift. There, the apostle Paul teaches that a spiritual gift is an enabling of the Holy Spirit given to regenerate individuals to exalt the lordship of Christ, serve the common good of others, to be used in love for others’ edification, and exercised in an orderly manner. Therefore, the idea of an individualized, private communing contradicts the meaning of New Testament spiritual gifts and renders a gift of tongues as unsubstantiated from Scripture.

The transitional nature of redemptive history in the first century.

Tragically, Israel had spurned Yahweh for centuries, culminating in the rejection of her Messiah. Consequently, God judged Israel in faithfulness to his word and covenant warnings. In part, this judgment involved setting Israel aside for the sake of the church. God would no longer center his redemptive plan on the ethnic nation of Israel, but a spiritual nation; the church. Acts records this glorious transition, as the Spirit empowered believers to make disciples from and among all nations. The idea of an individualized private prayer language contradicts the redemptive historical purpose of the gift of languages in the transitional time of Acts.

In a very vivid way, the God of the nations showed with the gift of languages that one need not immerse themselves in Israeli ethnicity to enter his favor. Believers need no not speak Hebrew and become a Jewish proselyte. Instead, God miraculously enabled people to speak the languages of the nations in order to speak the good news of Christ to the nations. Thus, the transitional nature of salvation history in the first century forbids the idea that this gift was a private prayer language. In no way is it a private phenomenon, but a corporate marvel for the nations and in judgment of Israel (cf. 1 Cor. 14:21).

Jesus’ teaching on prayer in Matthew 6:7.

In Matthew 6:7, Jesus teaches Christians how to pray:

“And when you are praying, do not use meaningless repetition as the Gentiles do, for they suppose that they will be heard for their many words” (Matt 6:7).

The word translated “meaningless repetition,” is from the Greek verb, battalogeo. Similar to the TDNT (1:597), A.T. Robertson comments that the word carries the idea of “stammerers who repeat the words,” “babbling or chattering,” “empty repetition.” John Nolland says it’s the idea of the repetition of either intelligible or unintelligible sounds in order to multiply effectiveness (Osborne, Matthew, 226). Many commentators agree that the prefix, “batta,” is onomatopoetic. In other words, the prefix sounds similar to the thing it describes; prayers sounding something like, “batta, batta, batta.” Being onomatopoetic does not mean that the word exhaustively covers everything which it describes, but the general idea.

Christ forbids praying this way for two reasons. First, because it is characteristic of Gentiles (Matt 6:7). Praying in a way that piles up language, or non-language, unintelligible, or babbling sounds is prayer characteristic of those who do not know God. Second, our heavenly Father already knows what we need before we think to pray about it, thus we need not pray or worship in a non-earthly linguistic, unintelligible way (Matt 6:8). Therefore, Christian prayer must consist of simple, earthly languages to our God.

The context of 1 Corinthians 14.

Proponents of the gift of tongues often refer to 1 Corinthians 14 to support their position. In that chapter, the apostle Paul corrects the chaotic frenzy which characterized Corinthian church gatherings. The purpose of the chapter was not to give details on the practice of non-language utterances and trances (whether private or public practice), but just the opposite: intelligibility and orderliness must characterize Christian worship gatherings.

Paul is correcting error with respect to what a spiritual gift is and how things ought to operate in the corporate gathering. In the Corinthian congregation there appears to have been a frenzy surrounding this spiritual gift. Continue reading