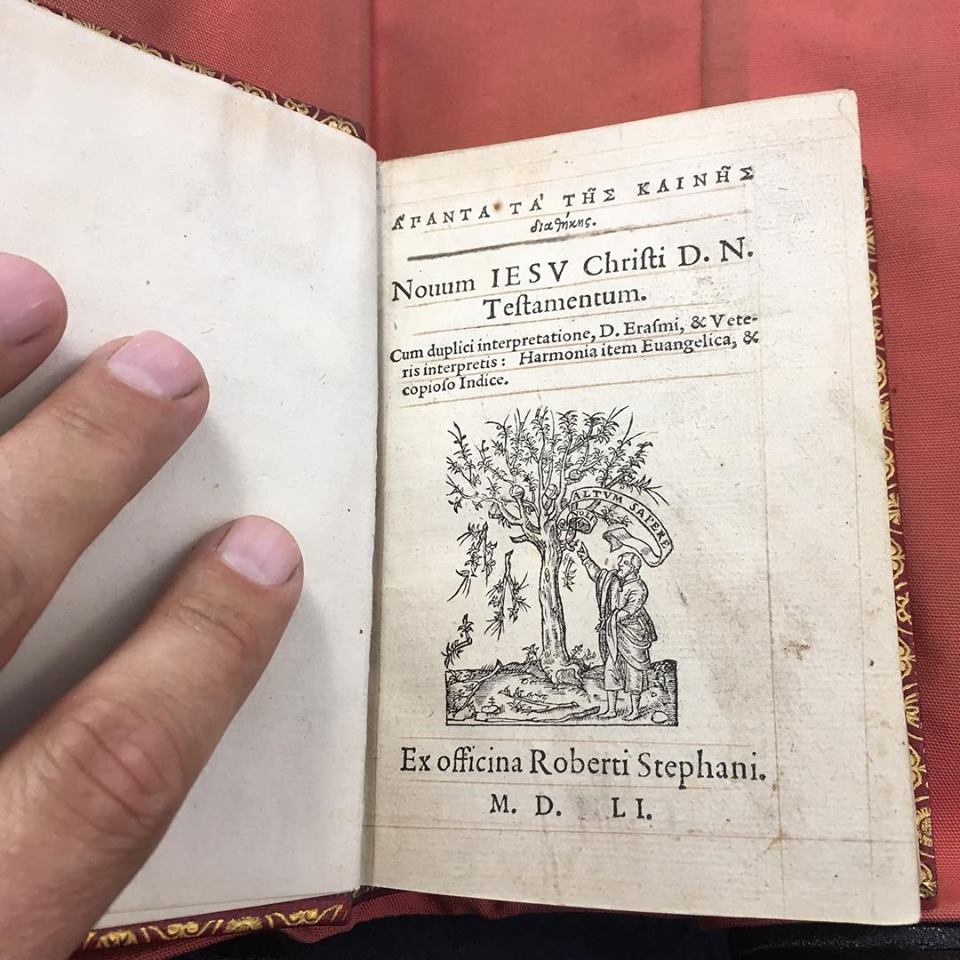

Stephanus’s 1551 New Testament – the first to print our modern verse system.

Stephanus’s 1551 New Testament – the first to print our modern verse system.

HT: Peter Williams

Where did the chapter and verse divisions in our Bibles come from?

Where did the chapter and verse divisions in our Bibles come from?

When Scripture was originally written, there were no chapter and verse divisions. These man-made additions to our Bibles came much later. It was Stephen Langton, an Archbishop of Canterbury in England, who added chapter divisions into the Latin Vulgate around A.D. 1227. A Jewish rabbi by the name of Nathan divided the Hebrew Bible (what we as Christians call the Old Testament) into verses in 1448. Then, Robert Estienne (also known as Stephanus) divided the chapters into verses in his Greek New Testament in 1551. The first English translation to make use of his verse divisions was the Geneva Bible of 1560.

That is something of the history behind the chapter and verse divisions. The question becomes “Was this development a good thing?”

My answer would be yes and no. It is fair to say there are pros and cons in this matter.

The designations are helpful in that they allow us to find a verse or passage in a short time. We can find a verse easily without the need to read an entire book of the Bible. The numbering system allows us to go straight to a verse or passage we wish to locate. This is a wonderful, practical benefit. Imagine if there were no chapter/verse divisions and a preacher asked the congregation to find the section of Isaiah dealing with the Suffering Servant of the Lord. How many people would find the passage? Not many, and certainly, not very many in a swift manner. However, if the preacher says, “Let’s turn to Isaiah chapter 53,” anyone in the audience with a Bible in hand can find the passage in just a few seconds. In this way, then, chapter and verse divisions are helpful and convenient when it comes to finding references and quotations.

But there is a downside—a major downside. These divisions make it especially easy for us to look at a verse in isolation, with no reference to its context. Many pages could be filled with examples. Just one is Philippians 4:13, where we read, “I can do all things through him who strengthens me.” This verse, in isolation, could be interpreted (falsely) to mean that Christ strengthens us to achieve any human endeavor, the “all things” referring to any conceivable task. An athlete might apply this by thinking the verse means Christ will strengthen him to win every race he enters—that this in fact is God’s promise to him. An author might use the verse as a promise that whatever he writes will be a best seller, and the Christian salesman might believe that he will be number 1 in company sales because of his relationship with Christ. Christ strengthens us to accomplish anything we set out to do.

But here’s the problem. The verse teaches nothing of the kind. The “all things” Christ does strengthen us to do refers to the things Paul wrote about in the previous sentences (vv. 10–12):

I rejoiced in the Lord greatly that now at length you have revived your concern for me. You were indeed concerned for me, but you had no opportunity. Not that I am speaking of being in need, for I have learned in whatever situation I am to be content. I know how to be brought low, and I know how to abound. In any and every circumstance, I have learned the secret of facing plenty and hunger, abundance and need.

Verse 13, “I can do all things through him who strengthens me,” has a context which, if ignored, leads to a false interpretation. The correct one is this: Whatever the situation, whatever the circumstance, whether in hardship or in much provision and abundance, whether there is plenty or whether we experience hunger and great need, God’s grace is more than abundant for us in Christ. He will strengthen us to endure whatever it is we have to face. That was true for Paul, and it is also true for all who trust in Christ. We can go through any event in life, whether it is a very good or a very hard thing, because the Lord Jesus Christ will strengthen us to do so. That is the meaning of Philippians 4:13.

The word arbitrary refers to something based on a random choice or personal whim, rather than reason or a sound logical system. Some of the chapter divisions in our Bibles are especially arbitrary. And this is another downside.

Just above, I mentioned Isaiah 53 and its reference to God’s Suffering Servant. Yet if we look at the words in their context, the passage starts speaking of this Servant in Isaiah 52:13, not Isaiah 53:1. Rather than Isaiah 53 starting where it does, a much better place for the insertion of a new chapter would have been at Isaiah 52, between verses 12 and 13. This would then allow us to see the entire passage in one section in our Bibles, rather than this unnecessary breaking up of the passage in a way that defies all logic and reason. And it is more than all right to say this, because in doing so, I am not being critical of God’s Word in any way. God’s Word is flawless, inerrant, and inspired. I am critical here only of what man has added to God’s inspired text in our Bibles. The chapter division here in Isaiah 53 is not helpful at all. Quite the opposite!

In summary, I think it is a good thing for us to have chapter and verse divisions in our Bibles, for the sake of convenience. However, it is important that we never forget that context is a key factor in forming a correct understanding of Scripture. When we forget context, misinterpretation is inevitable, and this is something we should always be vigilant to avoid.