A series of 4 short articles by Nathan Busenitz (original source thecripplegate.com)

A series of 4 short articles by Nathan Busenitz (original source thecripplegate.com)

Article 1: Are Tongues Real Languages?

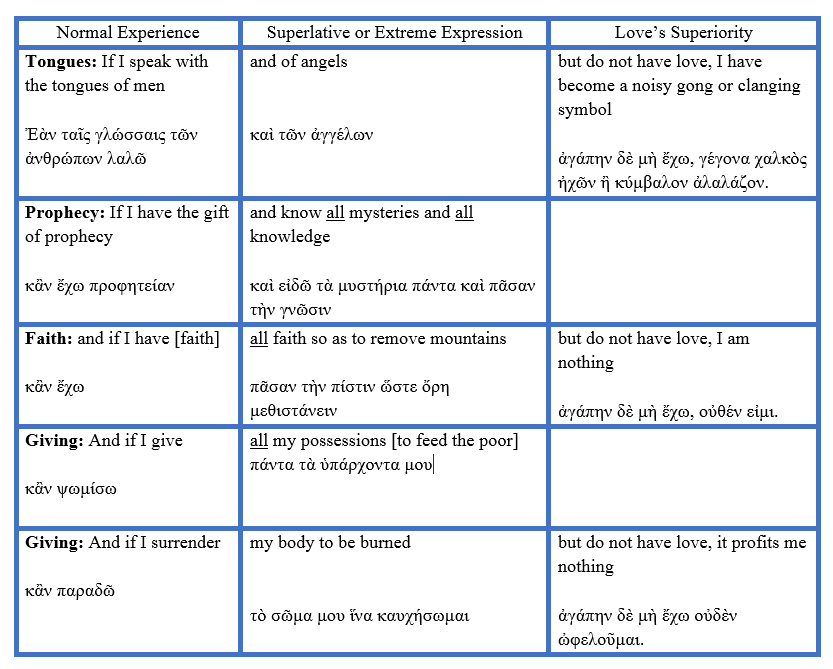

We begin today’s post with a question: In New Testament times, did the gift of tongues produce authentic foreign languages only, or did it also result in non-cognitive speech (like the private prayer languages of modern charismatics)? The answer is of critical importance to the contemporary continuationist/cessationist debate regarding the gift of tongues.

From the outset, it is important to note that the gift of tongues was, in reality, the gift of languages. I agree with continuationist author Wayne Grudem when he writes:

It should be said at the outset that the Greek word glossa, translated “tongue,” is not used only to mean the physical tongue in a person’s mouth, but also to mean “language.” In the New Testament passages where speaking in tongues is discussed, the meaning “languages” is certainly in view. It is unfortunate, therefore, that English translations have continued to use the phrase “speaking in tongues,” which is an expression not otherwise used in ordinary English and which gives the impression of a strange experience, something completely foreign to ordinary human life. But if English translations were to use the expression “speaking in languages,” it would not seem nearly as strange, and would give the reader a sense much closer to what first century Greek speaking readers would have heard in the phrase when they read it in Acts or 1 Corinthians. (Systematic Theology, 1069).

But what are we to think about the gift of languages?

If we consider the history of the church, we find that the gift of languages was universally considered to be the supernatural ability to speak authentic foreign languages that the speaker had not learned.

In the early church, the writings of Irenaeus, Hippolytus, Hegemonius, Gregory of Nazianzen, Ambrosiaster, Chrysostom, Augustine, Leo the Great, and others all support this claim. Here are just a few examples:

Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 329–390): “They spoke with foreign tongues, and not those of their native land; and the wonder was great, a language spoken by those who had not learned it. And the sign is to them that believe not, and not to them that believe, that it may be an accusation of the unbelievers, as it is written, ‘“With other tongues and other lips will I speak unto this people, and not even so will they listen to Me” says the Lord’” (The Oration on Pentecost, 15–17).

John Chrysostom (c. 344–407), commenting on 1 Cor. 14:1–2Open in Logos Bible Software (if available): “And as in the time of building the tower [of Babel] the one tongue was divided into many; so then the many tongues frequently met in one man, and the same person used to discourse both in the Persian, and the Roman, and the Indian, and many other tongues, the Spirit sounding within him: and the gift was called the gift of tongues because he could all at once speak divers languages” (Homilies on First Corinthians, 35.1).

Augustine (354–430): “In the earliest times, ‘the Holy Ghost fell upon them that believed: and they spoke with tongues,” which they had not learned, “as the Spirit gave them utterance.’ These were signs adapted to the time. For it was necessary for there to be that sign of the Holy Spirit in all tongues, to show that the Gospel of God was to run through all tongues over the whole earth” (Homilies on the First Epistle of John, 6.10).

In reaching this conclusion, the church fathers equated the tongues of Acts 2 with the tongues of 1 Corinthians 12–14, insisting that in both places the gift consisted of the ability to speak genuine languages.

The Reformers, similarly, regarded the gift of tongues as the supernatural ability to speak real foreign languages. By way of example, here is John Calvin’s treatment of 1 Corinthians 12:10):

John Calvin: “There was a difference between the knowledge of tongues, and the interpretation of them, for those who were endowed with the former [i.e. the gift of tongues] were, in many cases, not acquainted with the language of the nation with which they had to deal. The interpreters rendered foreign tongues into the native language. These endowments they did not at that time acquire by labor or study, but were put in possession of them by a wonderful revelation of the Spirit.” (Commentary on 1 Cor. 12:10)

To the names of the Reformers, we could add the names of the Puritans, and the names of theologians like Jonathan Edwards, Charles Hodge, Charles Spurgeon, and B.B. Warfield among many others. Continue reading