Excerpt from an article by Keith Throop responding to R. Scott Clark who does not allow for Reformed Baptists to call themselves “Reformed.” I’m with Keith on this:

Excerpt from an article by Keith Throop responding to R. Scott Clark who does not allow for Reformed Baptists to call themselves “Reformed.” I’m with Keith on this:

…I especially do not agree with his (R. Scott Clark’s) criticism of Reformed Baptists for their use of the term Reformed as a reference to themselves. Here are the specific comments with which I take exception:

Calling a Baptist “Reformed” is like calling Presbyterians “Baptist” because they believe in believer’s baptism. The Reformed churches do practice the baptism of unbaptized believers but they also baptize the infants of believers. No self-respecting, confessional Baptist should accept me as “Baptist” and Reformed folk should resist labeling anyone who rejects most of Reformed theology as “Reformed.”

There are several points to be made in response to these comments, but before I list them I want to make something clear, namely that I do not pretend to speak for all who would call themselves Reformed Baptists. I have entitled this post, “Why I Call Myself a Reformed Baptist,” and I hope that I may give a good, brief accounting for this in this post. But it must be said that I do not see myself as a leader of the movement, let alone one of its primary spokesmen. In fact, the movement is diverse enough not to claim any one person as the most appropriate spokesman. For example, back in 2007-2008 I conducted a poll on this blog that revealed some significant diversity among those who would call themselves Reformed Baptists.

With these caveats in mind, I will now address the above comments made by Clark. First, I do not agree at all with his assertion that “calling a Baptist ‘Reformed’ is like calling Presbyterians ‘Baptist’ because they believe in believer’s baptism.” I am, frankly, surprised that Clark would make use of such an analogy when he must know that what makes the Baptist position distinctive is not that we advocate the baptism of believers (which we certainly do) but rather that we advocate the baptism of believers only. When a Presbyterian begins to assert that position, then I will accept his calling himself a “Presbyterian Baptist,” even if he doesn’t hold to other historically distinctive Baptist positions, such as our view of church government, which asserts the autonomy of the local church in matters of governance. But, then, the term Presbyterian so used would clearly indicate this difference, wouldn’t it? And this is really no different than the way the term Baptist qualifies my use of the term Reformed.

Second, Clark’s comments seem to assume the idea that there is a monolithic historical understanding of the meaning of the English word reformed. But this is simply not true. There are broader and more narrow senses in which the word may be used, and not all of these require the specific understanding to which he apparently wishes to restrict usage of the term. In addition, I see no reason why a modifier cannot be attached to the word that in effect alters and qualifies its meaning so as to rule out the kind of misunderstanding that Clark is apparently concerned about. One such modifier – as I have already noted – is the term baptist, which immediately communicates a distinctive use of the word reformed.

Perhaps it would be helpful to discuss at least three senses in which I believe the term Reformed has been used, all of which have application to my own usage of the term when I call myself a Reformed Baptist. I will list three ways in which I believe I have seen the term used, beginning with the most broad sense and moving to the most narrow sense.

First, the term Reformed can be used in a broad sense to describe that which is changed for the better, and in our discussion it refers to the changes that were made by Protestants in their efforts to reform the Roman Catholic Church in accordance with Scripture. In this sense it could refer to any person or group that seeks to be consistent in reforming the church in this way. I believe John Quincy Adams had in mind this usage of the term in his famous little book Baptists: The Only Thorough Religious Reformers, and this is one sense in which I intend the word to be taken when I describe myself as a Reformed Baptist. It communicates my commitment to the principle indicated by the slogan semper reformanda (“always reforming”), and it declares my conviction that it is the Particular Baptists who have been more faithful reformers than their Presbyterian brothers, especially with regard to the issues of church government and baptism, as indicated above. Indeed, in this sense I think we have more right to use the term than they do.

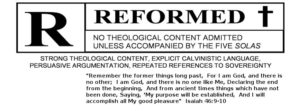

Second, the term reformed can refer to the broader Protestant tradition characterized by principles held by most of the early Reformers, and not just those in Geneva, for example. These principles may be summed up by the five Reformation precepts often referred to as “the solas.” These include the principle of sola scriptura (that Scripture alone is our ultimate authority), the principle of solus Christus (that we are saved by Christ alone), sola gratia (that we are saved by God’s grace alone), sola fide (that we are saved through faith alone), and soli Deo gloria (that all is to the glory of God alone). Thus when I call myself a Reformed Baptist I mean to indicate that I wholeheartedly embrace these distinctive principles of the Reformation.

Third, I agree that there is a more narrow use of the term as Clark affirms, namely to refer to those who follow the traditions that have come particularly from Calvin’s reforming work in Geneva. This would include not only the Swiss Reformed, but also the Scottish and Dutch Reformed and the numerous Presbyterian groups that have followed from each of these traditions. I also agree with Clark that we do not want to confuse Baptists with these Reformed groups. However, this is precisely why I call myself a Reformed Baptist.

The term Baptist clearly qualifies my use of the term Reformed. And when I use the terms together this way, I do not think I am doing anything essentially different than did those English Baptists who based the Baptist Confession of 1689 largely upon the Westminster Confession of Faith. They clearly wanted to identify themselves as in the mainstream of the Reformed tradition in one sense (particularly with regard to Calvinist soteriology and Covenant Theology), while at the same time distinguishing themselves in ways that demonstrated how they had reformed more thoroughly than had their Presbyterian brethren. This – together with the reasons already listed – is precisely why I call myself a Reformed Baptist.

I hope this post has helped to briefly clarify and defend my usage of the appellation Reformed Baptist to describe myself, and, despite Clark’s objections, I believe I have every right to use this description.