Robert M. Bowman Jr. (born 1957) is an American Evangelical Christian theologian specializing in the study of apologetics. In an article (here) he writes:

Kyle Roberts, a theologian at United Theological Seminary and a former evangelical, has written a blog article on Patheos entitled “Seven Problems with Inerrancy.” Roberts is an example of a growing number of theologians who argue that we should retain faith in Jesus Christ and even confess Scripture to be “inspired” or “the Word of God” while rejecting the belief that Scripture is inerrant. In this response, I will point out seven problems with Roberts’s position.

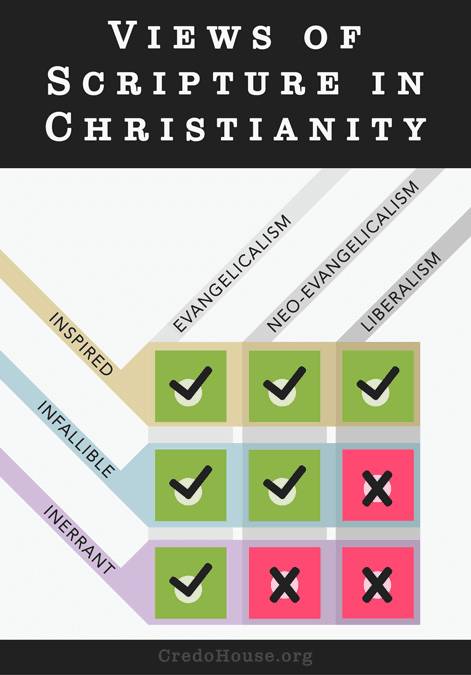

View of Scripture in Christianity – Inspiration, Inerrancy, Infallibility

View of Scripture in Christianity – Inspiration, Inerrancy, Infallibility

Note that I will not be arguing for the existence of God, the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, or even the status of the books of the Bible as Scripture in this article. I am addressing the views of people who affirm these things but deny the inerrancy of Scripture. My contention is that those who affirm those basic elements of Christianity are being inconsistent if they do not also accept the inerrancy of Scripture. I offer seven reasons in support of this conclusion.

1. Jesus Christ believed that Scripture is inerrant.

In an essay of over 1,700 words, Roberts offers various criticisms—actually far more than seven—of belief in the inerrancy of Scripture, yet he never addresses or even mentions the question of what Jesus Christ thought on the matter. This omission is quite common among Christian critics of inerrancy.

These critics often insist that Christ, not Scripture, is the central focus of Christian faith. Roberts, for example, asserts that “the Bible creates an occasion for us to narratively engage the story of Jesus–but it is the living Jesus that is the goal.”

Fair enough. Evangelicals certainly affirm that Jesus is the central focus and subject of Scripture, including the Old Testament, and that its goal is to lead us to faith in Jesus, as Jesus himself taught (Luke 24:27, 44-47; John 5:39-40). However, if we are serious about following Jesus Christ, we must accept his view of Scripture.

Just as evangelicals accept Christ’s claim that all of the Scripture is centered on him, they also accept Christ’s view that Scripture is the unerring Word of God.[1]

To learn how Jesus viewed Scripture, we must consult the most reliable sources of historical information about Jesus’ teachings and actions—the Gospels in the New Testament. A progressive or liberal Christian who believes that Jesus died on the cross and rose from the grave as reported in the canonical Gospels presumably would be willing to consult the Gospels at least as valuable sources of information about what Jesus said and did. When we do this, we discover that Jesus clearly accepted the conventional Jewish belief, taught especially by the Pharisees, that Scripture is unerring revelation from God.

Near the beginning of the Sermon on the Mount—which progressive and liberal Christians often assert epitomizes what it means to follow Jesus—we find that Jesus said the following:

“Do not think that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I did not come to abolish but to fulfill. For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass from the Law until all is accomplished” (Matt. 5:17-18).

That is a clear articulation of the traditional ancient Jewish view of Scripture as verbally inspired by God. The rest of the Gospels consistently attest that Jesus held this view.

Thus, that Jesus held to the inerrancy of Scripture is as certain as any fact about his teaching. If we were to reject the Gospels’ testimony as to Jesus’ view of Scripture, we would have no basis for knowing anything about Jesus’ teaching. An atheist or agnostic might be able to accept this conclusion, but it makes no sense for progressive Christians, most of whom speak very highly in particular of the Sermon on the Mount, to reject what the Gospels report concerning Jesus’ view of Scripture.

2. Christian non-inerrantists ignore or distort nearly two millennia of Christian affirmations of the absolute truth of Scripture.

Critics of inerrancy commonly allege that it is supposedly of recent vintage in the history of Christianity. We are often told that inerrancy is a distinctively modern theory of the nature of Scripture driven by Enlightenment rationalism. For example, the fifth objection that Roberts gives to inerrancy is that it “is simply too modernistic and ‘objectivist’ in orientation.” If that were true, it would be grounds for at least questioning the idea of inerrancy. However, it’s simply not true. Consider what just three of the greatest figures in church history said on the subject:

It is to the canonical Scriptures alone that I am bound to yield such implicit subjection as to follow their teaching, without admitting the slightest suspicion that in them any mistake or any statement intended to mislead could find a place.

Augustine of Hippo: “It is to the canonical Scriptures alone that I am bound to yield such implicit subjection as to follow their teaching, without admitting the slightest suspicion that in them any mistake or any statement intended to mislead could find a place” (Letters 82.3).

Thomas Aquinas: “Only to those books or writings which are called canonical have I learnt to pay such honour that I firmly believe that none of their authors have erred in composing them” (Summa theologiae 1a.1.8).

Martin Luther: “Everyone knows that at times they have [the early church fathers] erred as men will; therefore, I am ready to trust them only when they prove their opinions from Scripture, which has never erred” (Weimarer Ausgabe, 7:315). Continue reading