Rick Phillips and Ligon Duncan discuss the means of grace in the life of a Christian:

Monthly Archives: January 2015

Belieeeeeeve in Yourself!!!!

The Doctrine of Divine Impassibility

A Brief Statement on Divine Impassibility by then He is impassible. If God did in fact experience inner emotional changes, He would be mutable. To suggest otherwise would be to affirm that God was less than perfect to begin with: if He changes it is either for the better or for the worse, neither of which is consistent with the biblical data concerning God.

What the Doctrine Does Not Mean

The doctrine of divine impassibility does not mean that God is without affections. The Bible is clear: God is love (1 John 4:8, 16). The Bible consistently teaches that God does relate to His creatures in terms of love, goodness, mercy, kindness, justice and wrath. An affirmation of divine impassibility does not mean a denial of true affections in God. However, these descriptions of God’s character are not to be understood as changing or fluctuating things. For example, the 2 London Confession of Faith of 1677/1689 affirms impassibility (God is “without passions”) and then goes on to describe God as “most holy, most wise, most free, most absolute…most loving, gracious, merciful, long-suffering, abundant in goodness and truth…” The affirmation of impassibility does not result in removing affections from God; rather, the affirmation of impassibility upholds the fact that God is most loving because He cannot decrease nor increase; He is love! The doctrine of divine impassibility actually stresses the absolute-ness of affections in God.

Objections to the Doctrine

Some modern authors have challenged the classical doctrine of impassibility. While there are several reasons for this, two of the most persuasive ones seem to be (1) the biblical descriptions of change occurring in God and (2) the fact that Jesus Christ suffered.

In the first place, when Scripture speaks of change occurring in God, these passages do not describe actual inner emotional changes in God, but rather these passages are a means whereby God communicates “in the manner of men” so that He can effectively reveal His unchanging character to man. For instance, when Scripture speaks of God “repenting” (Genesis 6:6; Judges 2:18; 10:16; etc.), these are called anthropopathic statements. An anthropopathism is when the biblical author ascribes human emotion to God. While this may be a new word to many, most Christians are familiar with the word anthropomorphism. An anthropomorphism is used by the biblical authors when they ascribe human characteristics to God; i.e. when the Scripture says God has eyes, or a mighty right arm, or that He comes down to dwell on Mount Sinai (2 Chronicles 16:9; Isaiah 62:8; Exodus 19:20). Such descriptions are accommodations to man that are designed to communicate certain truths to man. In the same way, anthropopathisms are not descriptions of actual change in God, but are a means to communicate something concerning the character of the infinite God to man in language designed to be comprehended by man who is limited by his finite capacities.

Secondly, the sufferings that Jesus Christ went through were real. He was despised and rejected by men, He was betrayed by Judas, delivered into the hands of the Romans, and at the request of the unbelieving Jews, He was crucified. It is important to remember that Jesus Christ was unique: He is one glorious Person with two natures, human and divine. Christianity from the New Testament period on always predicated the suffering of Christ to His human nature. In other words, Christ as God did not suffer and die, but Christ as Man. There are not two Christs, but one Christ who has two natures. To confine the suffering and death of Christ to His humanity protects divine impassibility. Conversely, impassibility protects from the notion of a God who suffers and dies.

Conclusion

In conclusion, there is much more that can be said. The goal with this post is simply to provide a basic definition, explanation, and to highlight why the doctrine is essential. It is crucial to understand that it is the doctrine of impassibility that secures God’s relational character to His creatures; it alone provides the foundation for the confession’s declaration that God is “most holy, most wise, most free, most absolute…most loving, gracious, merciful, long-suffering, abundant in goodness and truth…”

Another Response to Newsweek

What does it mean to be “Reformed”?

Speaking theologically, what does it mean to be “Reformed”?

Speaking theologically, what does it mean to be “Reformed”?

I came across this list which was put together by Brandon Solberg, and believe it to be a very helpful, useful guide:

Historically Reformed

– Affirm the great “sola’s” (Latin for “only”) of the Reformation.

Sola Gratia…Grace Alone

Sola Fide…Faith Alone

Solus Christus…Christ Alone

Sola Scriptura…Scripture Alone

Soli Deo Gloria…To the Glory of God Alone

To summarize, salvation by Grace Alone, through Faith Alone, in Christ Alone, according to the Scriptures Alone, to the Glory of God Alone.

– Affirm and promote a profoundly high view of the supremacy and sovereignty of God in all things and sees God as actively involved in His creation, governing and overseeing all the affairs of men. cf. Psalm 115:3; Job 34:14-15; 37:6-13; Daniel 4:35.

– Affirm the utter dependence of sinful man upon God in all things, especially concerning salvation.

– Affirm the Doctrines of Grace (commonly referred to as Calvinism), which display God as the author of salvation from beginning to end.

The acrostic TULIP (which is a summation of the Canons of Dort) is the most familiar way of delineating the doctrines of Grace. TULIP is made up of 5 points, which are:

* T – Total Depravity

* U – Unconditional Election

* L – Limited Atonement

* I – Irresistible Grace

* P – Perseverance, and Preservation, of the Saints

– Creedal – To affirm the great creeds of the historic, orthodox church.

The Apostles’ Creed

The Nicene Creed

The Definition of Chalcedon

– Confessional – To affirm AT LEAST ONE of the great confessions of the historic orthodox church.

* The Westminster Standards

– The Westminster Confession of Faith

– The Westminster Longer Catechism

– The Westminster Shorter Catechism

* Reformed Baptist Standards

– 1689 London Baptist Confession of Faith

– The Baptist Catechism

– Orthodox Catechism

* The Three Forms of Unity

– The Belgic Confession of Faith

– The Heidelberg Catechism

– The Canons of Dortrecht

– Covenantal – To affirm the great covenants of Scripture and see those covenants as the means by which God interacts with and accomplishes His purposes in His creation, with mankind. The Scriptures contain numerous examples of God “covenanting” with man, establishing and ordaining a variety of covenants.

– A high view of Scripture, in it’s necessity, infallibility, sufficiency and internal consistency, and our dependence upon it to learn what God has revealed about Himself, His commands, and His way of salvation.

– A high view of the church in preaching (the exposition and application of God’s Word), the ordinances, discipline, prayer, worship (Regulative Principal), fellowship, and evangelism, all encompassed in the keeping of the Christian Sabbath, commonly called the Lord’s Day.

– A distinctly Biblical, Christian worldview that permeates all of life, a life lived in the world, but at the same time, a life not oriented to the world and it’s standards, but oriented to God’s Word.

– A clear understanding of the distinction between, and relationship of, Law and Gospel.

The Law has Three Uses:

1) The civil use. The law serves the commonwealth or body politic as a force to restrain sin. The law restrains evil through punishment. Though the law cannot change the heart, it can inhibit sin by threats of judgment, especially when backed by a civil code that administers punishment for proven offences.

2) The pedagogical use. The law also shows people the perfect righteousness of God, and their sinfulness which deserves punishment, and points them to mercy and grace outside of themselves, found in the Gospel alone.

3) The moral, normative, sanctifying use. The moral standards of the law provide guidance for believers as they seek to live in humble gratitude for the grace God has shown us. This use of the law is for those who trust in Christ and have been justified by grace alone, through faith alone, apart from works.

The 2nd use of the Law and its perfect requirement points us to the Gospel (good news) of the purchased redemption and free grace of the Son, for God’s people, and the Gospel, once applied by the Holy Spirit, then points us back to the third use of the Law in delight to obey its commands to the glory of God as a new creation in Christ Jesus.

What is Really Happening in the Lord’s Supper?

Mariolatry

I can only imagine what the Lord will one day say to those who so clearly blaspheme Him by means of this prayer and likewise disrespect His mother in this way:

“O Mother of Perpetual Help, thou art the dispenser of all the goods which God grants to us miserable sinners, and for this reason he has made thee so powerful, so rich, and so bountiful, that thou mayest help us in our misery. Thou art the advocate of the most wretched and abandoned sinners who have recourse to thee. Come then, to my help, dearest Mother, for I recommend myself to thee. In thy hands I place my eternal salvation and to thee do I entrust my soul. Count me among thy most devoted servants; take me under thy protection, and it is enough for me. For, if thou protect me, dear Mother, I fear nothing; not from my sins, because thou wilt obtain for me the pardon of them; nor from the devils, because thou art more powerful than all hell together; nor even from Jesus, my Judge himself, because by one prayer from thee he will be appeased. But one thing I fear, that in the hour of temptation I may neglect to call on thee and thus perish miserably. Obtain for me, then, the pardon of my sins, love for Jesus, final perseverance, and the grace always to have recourse to thee, O Mother of Perpetual Help.”

From the book “Devotions in Honor of Our Mother of Perpetual Help” – Quoted by Dr. James White in his book “Mary—Another Redeemer?” (pp. 9–10)

Through it all

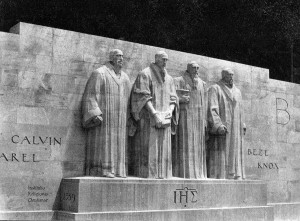

Calvin’s Geneva

John Calvin’s Geneva

BY W. J. GRIER

Geneva at the beginning of the sixteenth century was a city of some thirteen thousand people. Its situation near the best Alpine passes made it an important trading center. Prof. H. D. Foster of Yale has given a picture of the city and its people:

The Genevans, in fact, were not a simple, but a complex, cosmopolitan people. There was, at this crossing of the routes of trade, a mingling of French, German and Italian stock and characteristics; a large body of clergy of very dubious morality and force; and a still larger body of burghers, rather sounder and far more energetic and extremely independent, but keenly devoted to pleasure. It had the faults and follies of a medieval city and of a wealthy center in all times and lands; and also the progressive power of an ambitious, self-governing, and cosmopolitan community.

At their worst, the early Genevans were noisy and riotous and revolutionary; fond of processions and “mummeries” (not always respectable or safe), of gambling, immorality and loose songs and dances; possibly not over-scrupulous at a commercial or political bargain; and very self-assertive and obstinate. At their best, they were grave, shrewd, business-like statesmen, working slowly but surely, with keen knowledge of politics and human nature; with able leaders ready to devote time and money to public progress; and with a pretty intelligent, though less judicious, following.

In diplomacy they were as deft, as keen at a bargain and as quick to take advantage of the weakness of competitors, as they were shrewd and adroit in business. They were thrifty, but knew how to spend well; quick-witted, and gifted in the art of party nicknames. Finally, they were passionately devoted to liberty, energetic, and capable of prolonged self-sacrifice to attain and retain what they were convinced were their rights. On the borders of Switzerland, France, Germany and Italy, they belonged in temper to none of these lands; out of their Savoyard traits, their wars, reforms and new-comers, in time they created a distinct type, the Genevese.1

Williston Walker says that “no city in Christendom had had a more eventful or stormier history than Geneva during the generation and especially during the decade preceding Calvin’s coming.” Indeed through the fifteenth century and into the third decade of the sixteenth, there were three parties contending for the control: (1) the bishop of Geneva, (2) the House of Savoy, and (3) the citizens of Geneva. The bishop was in theory the sovereign of the city under the overlordship of the Emperor. The Duke of Savoy had certain rights in the city and tried to gain control of both bishop and townsmen.

As early as 1387 the townsmen secured from the bishop the sanction of certain rights, known as “The Franchises.” The chief of these was to gather in general assembly (or council) to choose magistrates. Four syndics or magistrates were to be chosen annually and a treasurer to be elected for three years, and the judgment of cases involving the laity was taken from the bishop’s court and given to the magistrates. There speedily grew up the Little Council, composed of the four syndics with the syndics of the preceding year plus counsellors elected by the syndics in office. At first this Council varied in number, but it came to be fixed at twenty-five. It was charged with the administration of the rights of the citizens. Continue reading

The God of the Old Testament

have wrestled to reconcile God’s holy justice with the seeming brutality of God’s judgments, especially in the Old Testament.

Before facing the difficulties head on and “staring the Old Testament God in the face,” Sproul rapidly dispatches some of the common yet unacceptable solutions to this problem. Then, instead of choosing some of the easier passages to explain and defend, Sproul takes head-on the most difficult and offensive passages in the Bible:

* The judgment of Nadab and Abihu for offering an unauthorized sacrifice (Lev. 10:1-3).

* The judgment on Uzzah for touching the ark (1 Chron. 13:7-11).

* Capital punishment for multiple crimes.

* The command given to Israel to slaughter thousands of Canaanites.

* The killing of Christ on the cross.

This chapter on God’s holy justice is the most outstanding chapter in an outstanding book, and, I believe, one of the greatest chapters Sproul has ever written. Although he deals with each of the above passages in turn, here’s my attempt to gather together and summarize the common threads in each section:

God’s judgments were pre-announced

In the cases of Nadab, Abihu, and Uzzah, God cannot be accused of unexpected, whimsical, or arbitrary judgment. Rather, God gave clear instructions and unmistakeable prohibitions and, in the case of Uzzah at least, clear and unmistakeable sanctions for disobedience (Ex. 30:9-10; Num. 4:15-20). These were not innocent men and these were not sins of ignorance.

God’s judgments are holy

As God’s justice is according to His holy character, His justice is never divorced from His righteousness. He never condemns the innocent, clears the guilty, or punishes with undue severity.

God’s judgments are delayed

Although the New Testament seems to reduce the number of capital offenses, even the Old Testament represents a massive reduction in capital crimes from original list – instant death for each and every sin.

The OT, therefore, is a record of the grace of God, because every sin is a capital offense and deserving of death. The issue is not why does God punish sin but why does He permit ongoing human rebellion and ongoing human existence. The OT is a record of a God who is patient in the extreme with a rebellious people, delaying the full measure of justice so that grace would have time to work.

God’s judgments are against sin

We don’t understand God’s judgments because we don’t understand sin. Sin is cosmic treason – treason against a perfectly pure sovereign. It misrepresents God whose image we are called to bear, and it violates others – injuring, despoiling, and robbing them. In commanding the Israelites to slaughter the Canaanites, God was not giving injustice to Canaan and justice to Israel; He gave justice to Canaan and mercy to Israel. The Canaanites were not innocent, but a treasonous people who daily insulted God’s holiness (Deut. 9:4-6).

God’s judgments were approved by Jesus

Christ called the Old Testament God, “Father.” It was the Old Testament God who sent His son to save the world, and the Old Testament God’s will that Jesus came to do. It was zeal for the Old Testament God who slew Nadab and Abihu that consumed Christ (John 2:17).

God’s greatest judgment was experienced by Jesus

The most powerful act of divine vengeance in the Bible, and the most violent expression of God’s wrath and justice, is seen at the cross. If we have cause for moral outrage, let it be focused on the cross. Yet, the cross was the most beautiful and the most horrible example of God’s wrath. It was the most just and the most gracious act in history.

God’s judgments destroy entitlement

Since we tend to take grace for granted, God reminded Israel through His judgments that grace must never be assumed. God’s judgments challenge our secret sense of entitlement, and changes the question from “Why doesn’t God save everybody?” to “Why did God save me?” But if we insist on insisting on what we deserve, we will get justice, not mercy.