J. Gresham Machen counterintutively noted that “A low view of law always produces legalism; a high view of law makes a person a seeker after grace.” The reason this seems so counter-intuitive is because most people think that those who talk a lot about grace have a low view of God’s law (hence, the goals are reachable, the demands are doable.

I love this illustration from Max Lucado’s book, In the Grip of Grace, on how judgmental instincts are anchored in a low view of God’s law:

Judging others is the quick and easy way to feel good about ourselves. A convenience-store-ego-boost. Standing next to all the Mussolinis and Hitlers and Dahmers of the world, we boast, “Look God, compared to them I’m not that bad.”

But that’s the problem. God doesn’t compare us to them. They aren’t the standard. God is. And compared to him, Paul will argue, “There is no one who does anything good” (Rom. 3:12).

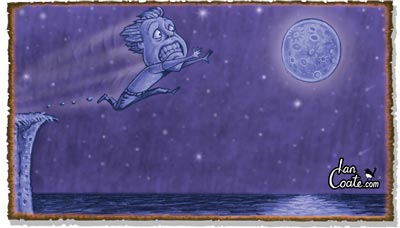

Suppose God simplified matters and reduced the Bible to one command: “Thou must jump so high in the air that you touch the moon.” No need to love your neighbor or pray or follow Jesus; just touch the moon by virtue of a jump, and you’ll be saved.

We’d never make it. There may be a few who jump three or four feet, even fewer who jump five or six; but compared to the distance we have to go, no one gets very far. Though you may jump six inches higher than I do, it’s scarcely reason to boast.

Now, God hasn’t called us to touch the moon, but he might as well have. He said, “You must be perfect, just as your Father in heaven is perfect” (Matt. 5:48). None of us can meet God’s standard. As a result, none of us deserves to don the robe and stand behind the bench and judge others. Why? We aren’t good enough. Dahmer may jump six inches and you may jump six feet, but compared to the 230,000 miles that remain, who can boast?

The thought of it is almost comical. We who jump three feet look at the fellow who jumped one inch and say, “What a lousy jump.” Why do we engage in such accusations? It’s a ploy. As long as I am thinking of your weaknesses, then I don’t have to think about my own. As long as I am looking at your puny jump, then I don’t have to be honest about my own. I’m like the man who went to see the psychiatrist with a turtle on his head and a strip of bacon dangling from each ear and said, “I’m here to talk to you about my brother.”