Dr. Mike Riccardi provides excellent insight in an article found here. He writes:

At the time in my spiritual life when I began to embrace the doctrines of grace, the one that was hardest to swallow was the L in our beloved TULIP acronym: limited atonement—or perhaps better stated (though ruining the acronym): particular redemption, or definite atonement. To make a long story short, I eventually came to see that the doctrine was biblical. Both the intent and extent of the atonement was divinely ordained to infallibly secure the salvation of all those whom the Father had chosen from before the foundation of the world (John 6:39; 10:11, 14–15; Acts 20:28; Eph 5:25). Jesus’ death didn’t simply make salvation possible, and then leave the appropriation of the cross’s benefits to the sovereign will of the sinner. No, it actually purchased the salvation of God’s elect (1Pet 2:24; Rev 5:9).

Interestingly, one of my chief objections to the doctrine wasn’t so much on textual or exegetical grounds. It was that it contradicted the way I had always heard the Gospel preached in evangelism. All around me, I heard the Gospel preached as if it was merely: “Jesus died for you, so you should believe in Him.” Evangelism boiled down to telling people that Jesus died specifically for them, and that, if He loved them so much that He would die for them, the least they could do was live for Him.

That message that I heard so often never really told people why Jesus died for them—i.e., to satisfy the Father’s righteous wrath against my sin that otherwise condemned me to hell. It was always, “Jesus died for you,” rather than, “Jesus died for you.” It was as if the cross was only a demonstration of love, rather than love demonstrated by the payment of the debt my sin incurred through Christ’s substitutionary death and resurrection.

So my embrace of the doctrine of particular redemption caused me to re-evaluate whether it was right to evangelize by calling people to faith on the grounds of Christ’s death for them. My back-and-forth reasoning went something like this: “I mean, I don’t know who the elect are, and if Christ’s death atoned only for the sins of the elect, how could I call a particular person to faith on the basis that Jesus died for them? Then again, it is possible that this person I’m speaking to was chosen by the Father in eternity past, and so then it would be true that Jesus paid for their sins. Besides, there are common-grace benefits that Jesus’ death secured for the elect and non-elect alike. In that sense, it may be true to say that Jesus died for someone (common grace for the non-elect) without actually atoning for their sins (special grace for the elect).”As you can see, I was quite confused.

But eventually my continued study of the Scriptures led me to realize that the Apostles and disciples never called people to faith on the basis of the extent of the atonement. Rather, they announced Jesus’ death as the purchase of the forgiveness of sins for all who would believe, and His resurrection as the vindication of Jesus’ righteousness and proof of their message.

Some time later, I read J. I. Packer’s classic, Evangelism & the Sovereignty of God. On pages 65 to 69 (in my copy), he articulated the thoughts I couldn’t quite capture in my own words. He explained the relationship between the extent of the atonement and evangelism. I want to share that section with you, in the hopes that it will equip you to more effectively proclaim the Gospel in a way that is faithful to Scripture.

We must not present the saving work of Christ apart from His Person. Evangelistic preachers and personal workers have sometimes been known to make this mistake. In their concern to focus attention on the atoning death of Christ, as the sole sufficient ground on which sinners may be accepted with God, they have expounded the summons to saving faith in these terms: ‘Believe that Christ died for your sins.’ The effect of this exposition is to represent the saving work of Christ in the past, dissociated from His Person in the present, as the whole object of our trust. But it is not biblical thus to isolate the work from the Worker. Nowhere in the New Testament is the call to believe expressed in such terms. What the New Testament calls for is faith in (en) or into (eis) or upon (epi) Christ Himself—the placing of our trust in the living Saviour, who died for sins.

The object of saving faith is thus not, strictly speaking, the atonement, but the Lord Jesus Christ, who made atonement. We must not in presenting the gospel isolate the cross and its benefits from the Christ whose cross it was. For the persons to whom the benefits of Christ’s death belong are just those who trust His Person, and believe, not upon His saving death simply, but upon Him, the living Saviour. ‘Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, and thou shalt be saved,’ said Paul. ‘Come unto me… and I will give you rest,’ said our Lord.

This being so, one thing becomes clear straight away: namely, that the question about the extent of the atonement, which is being much agitated in some quarters, has no bearing on the content of the evangelistic message at this particular point. … I am not at present asking you whether you think it is true to say that Christ died in order to save every single human being, past, present, and future, or not. Nor am I inviting you to make up your mind on this question, if you have not done so already. All I want to say here is that even if you think the above assertion is true, your presentation of Christ in evangelism ought not to differ from that of the man who thinks it false.

What I mean is this. It is obvious that if a preacher thought that the statement, ‘Christ died for every one of you,’ made to any congregation, would be unverifiable, and probably not true, he would take care not to make it in his gospel preaching. You do not find such statements in the sermons of, for instance, George Whitefield or Charles Spurgeon. But now, my point is that, even if a man thinks that this statement would be true if he made it, it is not a thing that he ever needs to say, or ever has reason to say, when preaching the gospel. For preaching the gospel, as we have just seen, means [calling] sinners to come to Jesus Christ, the living Saviour, who, by virtue of His atoning death, is able to forgive and save all those who put their trust in Him. What has to be said about the cross when preaching the gospel is simply that Christ’s death is the ground on which Christ’s forgiveness is given. And this is all that has to be said. The question of the designed extent of the atonement does not come into the story at all.

The fact is that the New Testament never calls on any man to repent on the ground that Christ died specifically and particularly for him. The basis on which the New Testament invites sinners to put faith in Christ is simply that they need Him, and that He offers Himself to them, and that those who receive Him are promised all the benefits that His death secured for His people. What is universal and all-inclusive in the New Testament is the invitation to faith, and the promise of salvation to all who believe. […]

The gospel is not, ‘believe that Christ died for everybody’s sins, and therefore for yours,’ any more than it is, ‘believe that Christ died only for certain people’s sins, and so perhaps not for yours.’ The gospel is, ‘believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, who died for sins, and now offers you Himself as your Saviour.’ This is the message which we are to take to the world. We have no business to ask them to put faith in any view of the extent of the atonement; our job is to point them to the living Christ, and summon them to trust in Him.

J. I. Packer, Evangelism & the Sovereignty of God (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 1961), 65–69.

Daniel B. Wallace, Ph.D writes:

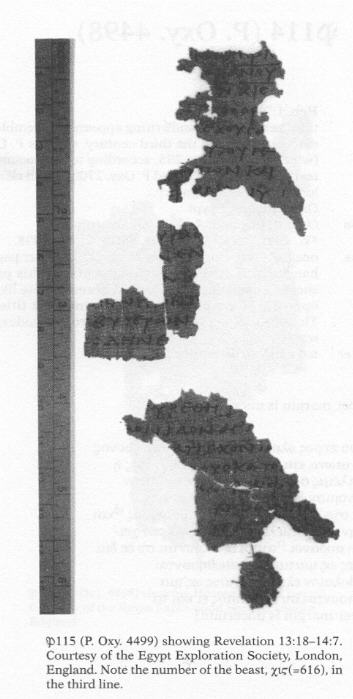

Daniel B. Wallace, Ph.D writes: Further, the number 616 was known in antiquity and was discarded in the second century. Irenaeus, the patristsic commentator, wrote a chapter on the number of the beast, arguing that in the better manuscripts of Revelation that he had seen the number was 666 instead of 616. To be sure, his perspective was theologically motivated (he gave the interpretation of 666 as striving for perfection [represented by the number 7] but never able to achieve it). But the fact that he was writing in the second century tells us that BOTH numbers existed at that time. It may well have been Irenaeus’ input that caused scribes to alter the text to 666 if 616 was in the exemplar that they used.

Further, the number 616 was known in antiquity and was discarded in the second century. Irenaeus, the patristsic commentator, wrote a chapter on the number of the beast, arguing that in the better manuscripts of Revelation that he had seen the number was 666 instead of 616. To be sure, his perspective was theologically motivated (he gave the interpretation of 666 as striving for perfection [represented by the number 7] but never able to achieve it). But the fact that he was writing in the second century tells us that BOTH numbers existed at that time. It may well have been Irenaeus’ input that caused scribes to alter the text to 666 if 616 was in the exemplar that they used.