Article 1: Seduced by Mysticism

Article 1: Seduced by Mysticism

(original source here)

Personal experiences and feelings are dangerous sources from which to derive one’s theology. The subjective impressions of reprobate minds rarely reflect concrete truth. Our most pressing need is for the fixed, external, objective, and unshakable truth found in God’s inerrant Word.

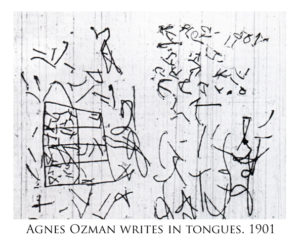

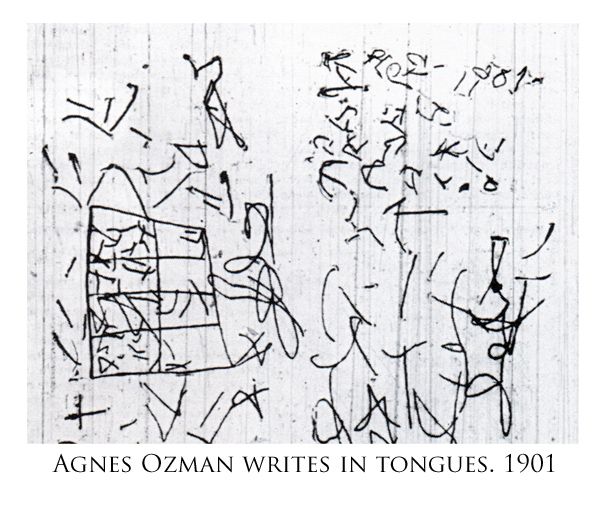

But even in the church, the allure of mystical experience regularly trumps the heavy lifting Bible study requires. The popularity of self-appointed prophets, outlandish claims of trips to heaven, and bizarre charismatic manifestations show that mysticism is alive and well in modern evangelicalism.

As one authority on mysticism has written, “A mystical experience is primarily an emotive event, rather than a cognitive one.” [1] The emotive event apart from cognitive functioning (an emotional high while the intellect is passive) has become for many Christians the ultimate spiritual experience. Multitudes have concluded that God’s most powerful work in our lives is not in the realm of truth but in the realm of emotion. This idea is rapidly changing the face of evangelicalism.

The Battle for Truth over Experience

Evangelicals have historically waged their most important battles in defense of truth and sound doctrine—and against an undue emphasis on emotion and experience. The early fundamentalist movement was a broad-based coalition of evangelicals who understood that sound doctrine is the litmus test of authentic faith. They defined true Christianity in terms of its essential doctrines. The doctrines they labeled fundamental were nothing new; these were truths all Christians had held in common since before the Protestant Reformation. But the fundamentalists were responding to the threat of liberalism, which was attacking doctrines at the very core of the historic Christian faith.

Liberals argued that Christianity is supposed to be an experience, not a doctrine. They wanted to discard the core of Christian doctrine but continue to call themselves Christians on the basis of their lifestyle. The original fundamentalists rescued evangelicalism from the liberal threat by unashamedly declaring that Christianity must be doctrine before it can be legitimate experience. Christianity is grounded in truth, they maintained, and no experience can be part of authentic Christianity if its origin is not in essential Christian truth. That is why they put such an emphasis on doctrine.

Today’s evangelicals are losing the will to hold that line. Voices within the camp are now suggesting that experience may be more important than doctrine after all. The evangelical consensus has shifted decidedly in the past three decades. Our collective message is now short on doctrine and long on experience. Thinking is deemed less important than feeling. Ironically, we have succumbed to the very ideas that the early fundamentalists argued so fiercely against. We have absorbed the same existential influences they fought so hard to overthrow.

Modern evangelicals can no longer define their identity in terms of doctrines they hold in common because the movement has become fragmented doctrinally. The obvious solution would be to return to our common doctrinal roots. Unfortunately, the panacea usually offered instead is an appeal to soften our doctrinal stance and unite on the basis of common experiences. This may be the most serious assault on truth evangelicalism has ever faced, because it comes from within the movement and has met little resistance.

Lest anyone misunderstand, I am by no means appealing for doctrine divorced from experience, or truth apart from love. That would be worthless. The apostle James said it this way: “Just as the body without the spirit is dead, so also faith without works is dead” (James 2:26). Truth genuinely believed is truth acted upon. Real faith always results in lively experience, and this frequently involves deep emotion. I am wholly in favor of those things. But genuine experience and legitimate emotions always come in response to truth; truth must never become the slave of sheer emotion or unintelligible experiences.

At least that is the position evangelicalism has always taken. Are we prepared to abandon that conviction? Shall we now exalt experience at the expense of sound doctrine? Will we allow emotion to run roughshod over truth? Will evangelicalism be swept away with unbridled passion?

Old Battle, New Battlefield

Unfortunately, those things are already happening by default. Sound doctrine and biblical truth are practically missing from evangelical pulpits. They have been replaced by show business, pop psychology, partisan politics, motivational talks, and even comedy. Many pastors and church leaders are woefully ill-equipped to teach doctrine and Scripture. The love of sound doctrine that has always been a distinctive of evangelicalism has all but disappeared.

Add a dose of mysticism to this mix, and you have the recipe for unmitigated spiritual disaster. People begin seeking spiritual experiences in everything except the objective truth of Scripture. Sheer emotion begins to replace any sensible understanding of truth and anyone who dares voice doctrinal concerns is likely to be labeled legalistic (or worse). More and more people are therefore encouraged to seek God via emotional experiences that are essentially divorced from truth. They eventually get caught in an endless cycle where, in order to maintain the emotional high, each experience must be more spectacular than the preceding one.

God’s people need to recognize danger before getting swept up in unrestrained emotion. In the days ahead we’ll examine the various fronts where mysticism is invading the church, considering both historic and current examples. Join us as we learn to detect and resist the insidious incursion of mysticism into our local churches.

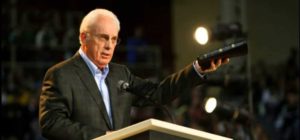

Article 2: (Adapted from Reckless Faith by Dr. John MacArthur – original source here)

Pastors need Bereans in their congregations—members “who received the word with great eagerness, examining the Scriptures daily to see whether these things were so” (Acts 17:11). Those who would teach God’s Word must be held accountable to its exacting standards. Unfortunately, the opposite is true for those who desire to preach personal opinions and exegete experiences. Their very survival depends on their ability to suppress all theological scrutiny.

Defenders of mystical phenomena such as “holy laughter” frequently admonish critics that they are in danger of grieving, quenching, or worst of all, blaspheming the Holy Spirit. Often this is nothing more than a form of spiritual intimidation. But it usually proves quite effective, silencing the voice of reason and absolving the promoters of mystical phenomena from any responsibility to give a sound biblical basis for what they are doing.

Notice, however, that all the stern warnings against quenching the Spirit constitute a very obvious circular argument. They assume from the outset the very point they wish to establish—that these phenomena are the work of the Holy Spirit. This is the essence of the argument: if things happen we cannot explain or find a basis for in Scripture, we dare not question or challenge them. Such phenomena are de facto proof that the Holy Spirit is working. Thus sheer mysticism is equated with the moving of the Holy Spirit. Any discerning souls who attempt to “examine everything carefully” in accord with 1 Thessalonians 5:21 are warned that they are sinning against the Holy Spirit.

One of the fullest efforts to defend this perspective is a book by William DeArteaga titled Quenching the Spirit. The blurb on the book’s cover reads, “Examining Centuries of Opposition to the Moving of the Holy Spirit.” [1] This book is neither scholarly or accurate but must be addressed since many have used it in an effort to give historical legitimacy to charismatic mysticism. DeArteaga is convinced that all who oppose modern charismatic phenomena are simply latter-day Pharisees—and he implies that some may have already committed the unpardonable sin. [2]

Pharisaism becomes the metaphor for all that DeArteaga opposes. His appraisal of the Pharisees is revealing:

The Pharisees’ real problem came from two sources. First, they drastically overvalued the role of theology in spiritual life and made theological correctness the chief religious virtue. Somewhere in the process the primary command to love God and mankind was subordinated to correct theology. Second, they had a man-given confidence in their theological traditions as being the perfect interpretation of Scripture. They falsely placed their theology, referred to as the traditions of the elders, on the same level as Scripture. [3]

Notice that DeArteaga’s portrayal of pharisaism amounts to a not-so-subtle attack on theology—especially “theological correctness.” He implies that love for God is somehow in conflict with a concern for correct theology. He even pits sound theology against Scripture, suggesting that those concerned with “theological correctness” are guilty of placing their theology on the same level as Scripture.

But those are false dichotomies. Real love for God is inseparable from love of the truth. The heart that genuinely loves God will be inclined to truth (see 2 Thessalonians 2:10; 2 John 6). And true theological correctness is found only in an accurate understanding of Scripture (1 Timothy 6:3–4; Titus 1:9). Those determined to cast sound theology aside must also abandon Scripture (2 Timothy 4:2–3). Scripture and sound theology are not antithetical; they are indissolubly bound together. One simply cannot esteem Scripture highly yet scorn sound doctrine. One cannot love God and remain indifferent to His truth. Scripture is how He makes Himself known. So a sound understanding of Scripture is essential to a true knowledge of God.

Moreover, DeArteaga completely misunderstands the real error of pharisaism. The Pharisees were in no sense guilty of an undue emphasis on theological orthodoxy. If anything, their problem was the opposite. They weren’t careful enough in seeking to understand the Scriptures. In fact, they set Scripture aside in favor of their own rote traditions. Tradition, not theology, was their downfall. If they had stuck to Scripture and built their theology on that alone, they would not have fallen into error. Jesus confronted the Pharisees for their pride, their spiritual blindness, their legalism, their want of compassion, their love of power and recognition, and their lack of knowledge about the Word of God. At no time did He rebuke them for overemphasizing “theological correctness.”

DeArteaga’s book is a freewheeling romp through revisionist history. For example, he uses the Great Awakening as a model to show how “theological correctness” poses a threat to the working of the Holy Spirit. This argument is worth examining more closely, because the Great Awakening is becoming a favorite paradigm for modern-day mystics. But as we’ll see next time, that great eighteenth-century revival was actually derailed—not driven—by mystical phenomena.