Robert M. Bowman Jr. (born 1957) is an American Evangelical Christian theologian specializing in the study of apologetics. In an article (here) he writes:

Kyle Roberts, a theologian at United Theological Seminary and a former evangelical, has written a blog article on Patheos entitled “Seven Problems with Inerrancy.” Roberts is an example of a growing number of theologians who argue that we should retain faith in Jesus Christ and even confess Scripture to be “inspired” or “the Word of God” while rejecting the belief that Scripture is inerrant. In this response, I will point out seven problems with Roberts’s position.

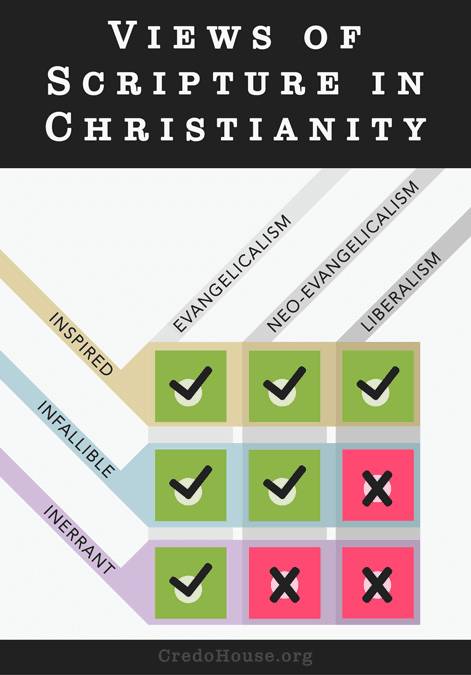

View of Scripture in Christianity – Inspiration, Inerrancy, Infallibility

View of Scripture in Christianity – Inspiration, Inerrancy, Infallibility

Note that I will not be arguing for the existence of God, the death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, or even the status of the books of the Bible as Scripture in this article. I am addressing the views of people who affirm these things but deny the inerrancy of Scripture. My contention is that those who affirm those basic elements of Christianity are being inconsistent if they do not also accept the inerrancy of Scripture. I offer seven reasons in support of this conclusion.

1. Jesus Christ believed that Scripture is inerrant.

In an essay of over 1,700 words, Roberts offers various criticisms—actually far more than seven—of belief in the inerrancy of Scripture, yet he never addresses or even mentions the question of what Jesus Christ thought on the matter. This omission is quite common among Christian critics of inerrancy.

These critics often insist that Christ, not Scripture, is the central focus of Christian faith. Roberts, for example, asserts that “the Bible creates an occasion for us to narratively engage the story of Jesus–but it is the living Jesus that is the goal.”

Fair enough. Evangelicals certainly affirm that Jesus is the central focus and subject of Scripture, including the Old Testament, and that its goal is to lead us to faith in Jesus, as Jesus himself taught (Luke 24:27, 44-47; John 5:39-40). However, if we are serious about following Jesus Christ, we must accept his view of Scripture.

Just as evangelicals accept Christ’s claim that all of the Scripture is centered on him, they also accept Christ’s view that Scripture is the unerring Word of God.[1]

To learn how Jesus viewed Scripture, we must consult the most reliable sources of historical information about Jesus’ teachings and actions—the Gospels in the New Testament. A progressive or liberal Christian who believes that Jesus died on the cross and rose from the grave as reported in the canonical Gospels presumably would be willing to consult the Gospels at least as valuable sources of information about what Jesus said and did. When we do this, we discover that Jesus clearly accepted the conventional Jewish belief, taught especially by the Pharisees, that Scripture is unerring revelation from God.

Near the beginning of the Sermon on the Mount—which progressive and liberal Christians often assert epitomizes what it means to follow Jesus—we find that Jesus said the following:

“Do not think that I came to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I did not come to abolish but to fulfill. For truly I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not the smallest letter or stroke shall pass from the Law until all is accomplished” (Matt. 5:17-18).

That is a clear articulation of the traditional ancient Jewish view of Scripture as verbally inspired by God. The rest of the Gospels consistently attest that Jesus held this view.

Thus, that Jesus held to the inerrancy of Scripture is as certain as any fact about his teaching. If we were to reject the Gospels’ testimony as to Jesus’ view of Scripture, we would have no basis for knowing anything about Jesus’ teaching. An atheist or agnostic might be able to accept this conclusion, but it makes no sense for progressive Christians, most of whom speak very highly in particular of the Sermon on the Mount, to reject what the Gospels report concerning Jesus’ view of Scripture.

2. Christian non-inerrantists ignore or distort nearly two millennia of Christian affirmations of the absolute truth of Scripture.

Critics of inerrancy commonly allege that it is supposedly of recent vintage in the history of Christianity. We are often told that inerrancy is a distinctively modern theory of the nature of Scripture driven by Enlightenment rationalism. For example, the fifth objection that Roberts gives to inerrancy is that it “is simply too modernistic and ‘objectivist’ in orientation.” If that were true, it would be grounds for at least questioning the idea of inerrancy. However, it’s simply not true. Consider what just three of the greatest figures in church history said on the subject:

It is to the canonical Scriptures alone that I am bound to yield such implicit subjection as to follow their teaching, without admitting the slightest suspicion that in them any mistake or any statement intended to mislead could find a place.

Augustine of Hippo: “It is to the canonical Scriptures alone that I am bound to yield such implicit subjection as to follow their teaching, without admitting the slightest suspicion that in them any mistake or any statement intended to mislead could find a place” (Letters 82.3).

Thomas Aquinas: “Only to those books or writings which are called canonical have I learnt to pay such honour that I firmly believe that none of their authors have erred in composing them” (Summa theologiae 1a.1.8).

Martin Luther: “Everyone knows that at times they have [the early church fathers] erred as men will; therefore, I am ready to trust them only when they prove their opinions from Scripture, which has never erred” (Weimarer Ausgabe, 7:315).

Obviously, the doctrine of the inerrancy of Scripture is not new, nor is it the product of modern, “objectivist” thinking. It was the standard Christian view of Scripture throughout most of the history of Christianity. What is new is the notion that Scripture can be accepted as the word of God while at the same time regarded as containing numerous errors, contradictions, outright falsehoods, and even immoral ideas.

It is of course possible that the traditional Christian view of Scripture is wrong. However, it is irresponsible for opponents of inerrancy to criticize inerrancy as supposedly a latecomer in Christian theology. Moreover, for those who profess to be Christians, the burden of proof is on those who reject the traditional view.

3. Christian opponents of inerrancy grant themselves the right to advance careful, qualified definitions of their view of Scripture but do not accord advocates of inerrancy the same right.

Robert’s first “problem” with inerrancy is that “there are so many definitions of inerrancy that it has become a mostly meaningless word.” Instead, he thinks we should prefer such terms as inspiration. Is Roberts unaware of the fact that there are many competing definitions of this term as well?

Most if not all generalizations require or presuppose some definition as well as some qualifications or contextual framework, but that does not make them useless or meaningless. The description of Scripture as “inspired,” which Roberts says he accepts, is meaningless without some context in which the description is informative. For example, one must know that the term inspired in Christian descriptions of Scripture reflects the context in which God is understood to be communicating to human beings through the vehicle of Scripture. This is a very different meaning from other uses of the term, as when a painter says that she was “inspired” by a recent sunset on the beach or when a filmmaker says that his film was “inspired” by a particular novel.

Theologians who deny the inerrancy of Scripture have offered a confusing plethora of definitions of the “inspiration” of Scripture:

The religious genius or insight of the authors

The spiritual power or experience of the authors

The spiritual transformative power of Scripture in the lives of those who read it

Those are just a few of the many proposed definitions.

In some cases, as in the case of Kyle Roberts, such theologians don’t even bother defining what they mean by “inspired”; they simply assert that Scripture can somehow be inspired without being inerrant.

4. Critics commonly criticize caricatures of inerrancy rather than engaging with the doctrine as evangelical theologians commonly understand it.

There are too many caricatured misrepresentations of the doctrine of inerrancy to address or even mention them all here. I will be content with commenting briefly on three of them.

First, inerrancy does not require taking every statement or passage in Scripture “literally.” As the Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy observes, proper interpretation of Scripture includes “taking account of its literary forms and devices.”[2]

Second, Roberts engages in obvious caricature when he asserts that the evangelical view of inspiration suggests that the Bible is a “book that just sort of drops out of the sky.” No evangelical thinks of the Bible that way. Roberts’s caricature would be generally appropriate in reference to the Qur’an or the Book of Mormon but not to the Bible as evangelicals view it.

Third, the concept of inerrancy does not deny the limitedness of our present knowledge. What Scripture teaches is inerrant, but Scripture does not teach us everything that we will know in glory (1 Cor. 13:12; 1 John 3:2), and what it does teach we know and understand quite imperfectly.

The first order of business when setting out to critique someone else’s view is to understand it (Prov. 18:13). Those who reject the doctrine of inerrancy are free to do so, but they need to address what evangelicals really teach about it, not straw-men caricatures that are easier to knock down.

5. The “inspired but not inerrant” position cannot explain what separates the books of the Bible as Scripture from other Jewish and Christian texts.

Christians who want to have their Scripture cake and eat it too rarely explain what distinguishes the books of the Bible, which they agree belong in the canon of Scripture, from other writings. For example, after trashing the Bible as an error-filled collection of writings containing absurdities and immoral teachings, Kyle Roberts concludes his essay by assuring us that he still likes the Bible because it facilitates a “relational knowledge of God.” Is this what makes some books Scripture and others not?

Only to those books or writings which are called canonical have I learnt to pay such honour that I firmly believe that none of their authors have erred in composing them

Different kinds of Christians might favor different books, but if what we are after, according to progressive Christians, is simply “relational” knowledge of God, all sorts of books might qualify. Take your pick of the Christian classics that have led people into a Christian experience of relationship to God:

Augustine’s Confessions

Thomas A Kempis’s Imitation of Christ

C. S. Lewis’s Mere Christianity

What do the books of the Bible have that these books don’t have?

For that matter, wouldn’t a progressive or liberal Christian think that a book like Lewis’s Mere Christianity is more likely to facilitate relational knowledge of God than, say, Numbers (which Roberts cited with some contempt) or Esther (which never even mentions God)? If that is the criterion by which some books belong in the Christian canon, there seems to be no reason to have a canon, since new books that help people find a relationship with God are continually being produced.

In short, in order for our affirmation of the inspiration of Scripture to be meaningful, we need to have a clear idea of what separates the books that are Scripture qualitatively from all other books. The traditional Christian view does this: Scripture, as the written word of God, is uniquely the wholly trustworthy verbal expression of truth from God. The “inspired but not inerrant” position does not.

6. Christian opponents of inerrancy typically slide back and forth between claiming merely that Scripture contains picayune errors and claiming that Scripture contains false claims and immoral teachings.

The position that Scripture is “infallible” but not “inerrant” has always been somewhat incoherent, but in recent years some teachers are making criticisms of the Bible that gut any profession of belief in the infallibility of Scripture.

Roberts, who criticizes inerrancy as supposedly demanding “factual precision” of Scripture (another straw-man caricature), opines that one might attribute “infallibility” to Scripture while refraining from affirming its inerrancy. But what sort of “infallibility” might be attributed to texts that Roberts characterizes as follows?

Did God really (I mean, really) command Moses to kill all the Midianite men and non-virgin women, but to keep the virgins alive for the soldiers (Num. 31)? In other words, did God command genocide, slavery, and sex trafficking? What do we do with all the violence, slavery, rape, and sexism in the Bible (see, for example, Phyllis Trible’s Texts of Terror)?

If the Bible is all that bad, describing it as “infallible” would appear to require some extraordinary special pleading. And some people claim that inerrancy dies the death of a thousand qualifications!

Please, don’t play word games by saying you believe that the Bible is the Word of God, that it is inspired and infallible, and then turn around and accuse its authors of teaching that God commanded genocide, slavery, and sex trafficking. Just admit it: you don’t really believe that the Bible is the Word of God. Rather, you think that it is the word of man, which sometimes is faithful to God and sometimes is not.

Roberts and those who think like him are not merely criticizing the evangelical doctrine of the inerrancy of Scripture; they are criticizing Scripture itself.

7. Critics of the inerrancy of Scripture fail to understand Scripture as much as they could because they too easily judge biblical texts to be in error instead of searching for explanations alongside other believers.

In a way, finding “error” in Scripture is easy: read until you run into something you don’t immediately understand or don’t like, and simply declare it a problem or error or mistake. This is what Kyle Roberts does toward the beginning of his article:

Did Elisha’s ax-head really float (2 Kings 6)?

Was Jonah really swallowed by a big fish and spat out 3 days later?

And so on. Roberts doesn’t even bother to answer his own questions; merely asking them is deemed sufficient to make the point that one cannot reasonably regard Scripture as inerrant. Apparently such miracle stories in the Old Testament are obviously problematic, in effect guilty of being unbelievable unless proven innocent.

Finding “errors” in Scripture is easy: find something you don’t understand or don’t like,…

Roberts is especially bothered by the account of the iron axe head floating. He argues that “there’s a big difference” between this story and the resurrection of Jesus because the axe head story has no “direct bearing” on our faith, whereas the resurrection “is the ground of our hope” in Jesus Christ. I agree with this comment as far as it goes. Of course, Jesus’ resurrection is far more important to our redemption and hope of eternal life. Even if the axe head story was fable or fiction, that wouldn’t undermine the historicity of the resurrection.

Everyone knows that at times they have [the early church fathers] erred as men will; therefore, I am ready to trust them only when they prove their opinions from Scripture, which has never erred

However, Roberts takes it one step further. He argues, not only that the axe head story is less important, but that it is an embarrassment. Apparently we’d be better off without it. What he never asks is this: Why is this story in Kings, and why is Kings in the Bible?

The miracle of the floating axe head[3] is one of many miracles attributed in Kings to the agency of Elijah and Elisha. Their miracles of food provision, healing, and resurrection anticipated the miracles of Jesus. The restoration of the axe head fits comfortably into the context of Elisha’s ministry.

Believers in the Christian God, if they question the axe story, must explain how they view the entire Elijah–Elisha narrative. The inspired-but-not-inerrant advocates rarely if ever do so. It’s one thing to express incredulity over a floating axe head. It’s quite another matter to dispute Elijah and Elisha’s authenticity as prophets. After all, the God who created the world would have no problem causing an axe head to float. I understand why atheists don’t believe in miracles, but Christians?

The most important miracle of history, of course, is Jesus’ resurrection from the dead. If we believe God could raise Jesus from the dead, we certainly should have no problem believing that God could raise an iron axe head from the bottom of a river. And in that comparison we probably have the key to understanding why, from a theological perspective, the story of Elisha and the floating axe head is in the Bible. It is one of the numerous signs in the Old Testament that point to Jesus Christ:

Sinking of the axe head (death of Jesus)

Surfacing of the axe head (resurrection of Jesus)

In the third century, Origen suggested that the stick typified the wood of the cross and the surfacing of the axe head the resurrection of the Head of the redeemed. Perhaps this is not as much of a reach as one might suppose.

Christ is indeed the central focus of the Christian canon. All Scripture points to Christ in some way. This includes the miracles that God did through his prophets in ancient Israel. It’s tragic that in the rush to find fault with inerrancy, some Christians miss this important truth.

1. Robert M. Bowman Jr., “Jesus and the Inerrancy of Scripture: A Simple Argument for Those Who Believe in Jesus,” Institute for Religious Research (August 2015), accessed August 21, 2015, https://bib.irr.org/jesus-and-inerrancy-of-scripture. ?

2. International Council on Biblical Inerrancy, The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy, accessed August 22, 2015, http://library.dts.edu/Pages/TL/Special/ICBI_1.pdf. ?

3. Robert M. Bowman Jr., “The Floating Axe Head in 2 Kings 6: Miracle or Fable?” Institute for Religious Research (2015), https://bib.irr.org/floating-axe-head-in-2-kings-6-miracle-or-fable, accessed August 21, 2015