Nathan Busenitz serves on the pastoral staff of Grace Church and teaches theology at The Master’s Seminary in Los Angeles. In he writes:

Are there apostles in the church today?

Are there apostles in the church today?

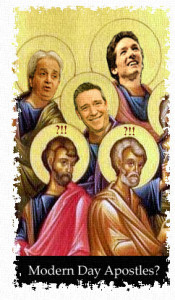

Just ask your average fan of TBN, many of whom consider popular televangelists like Benny Hinn, Rod Parsley, and Joel Osteen to be apostles. (Here’s one such example [see page 22].)

Or, you could ask folks like Ron, Dennis, Gerald, Arsenio, Oscar, or Joanne. They not only believe in modern-day apostleship, they assert themselves to be apostles.

A quick Google search reveals that self-proclaimed apostles abound online. Armed with a charismatic pneumatology and often an air of spiritual ambition, they put themselves on par with the earliest leaders of the church.

So what are Bible-believing Christians to think about all of this?

Well, that brings us back to the title of our post:

Are there still apostles in the church today?

At the outset, we should note that by “apostles” we do not simply mean “sent ones” in the general sense. Rather, we are speaking of those select individuals directly appointed and authorized by Jesus Christ to be His immediate representatives on earth. In this sense, we are speaking of “capital A” apostles – such as the Twelve and the apostle Paul.

It is these type of “apostles” that Paul speaks of in Ephesians 2:20; 3:5); 4:11 and in 1 Corinthians 12:29–30. This is important because, especially in Ephesians 4 and in 1 Corinthians 12–14, Paul references apostleship within the context of the charismatic gifts. If “apostleship” has ceased, it gives us grounds to consider the possibility that other offices/gifts have ceased as well. If the apostles were unique, and the period in which they ministered was unique, then it follows that the gifts that characterized the apostolic age were also unique.

The question then is an important one, underscoring the basic principle of the cessationist paradigm – namely, the uniqueness of the apostolic age and the subsequent cessation of certain aspects of that age.

There are at least five reasons why we believe there are no longer any apostles in the church today (and in fact have not been since the death of the apostle John).

1. The Qualifications Necessary for Apostleship

First, and perhaps most basically, the qualifications necessary for apostleship preclude contemporary Christians from filling the apostolic office.

In order to be an apostle, one had to meet at least three necessary qualifications: (1) an apostle had to be an eyewitness of the resurrected Christ (Acts 1:22; 10:39–41; 1 Cor. 9:1; 15:7–8); (2) an apostle had to be directly appointed by Jesus Christ (Mark 3:14; Luke 6:13; Acts 1:2, 24; 10:41; Gal. 1:1); and (3) an apostle had to be able to confirm his mission and message with miraculous signs (Matt. 10:1–2; Acts 1:5–8; 2:43; 4:33; 5:12; 8:14; 2 Cor. 12:12; Heb. 2:3–4). We might also note that, in choosing Matthias as a replacement for Judas, the eleven also looked for someone who had accompanied Jesus throughout His entire earthly ministry (Acts 1:21–22; 10:39–41).

Based on these qualifications alone, many continuationists agree that there are no apostles in the church today. Thus, Wayne Grudem (a continuationist) notes in his Systematic Theology, “It seems that no apostles were appointed after Paul, and certainly, since no one today can meet the qualification of having seen the risen Christ with his own eyes, there are no apostles today” (p. 911).

2. The Uniqueness of Paul’s Apostleship

But what about the apostle Paul?

Some have contended that, in the same way that Paul was an apostle, there might still be apostles in the church today. But this ignores the uniqueness with which Paul viewed his own apostleship. Paul’s situation was not the norm, as he himself explains in 1 Corinthians 15:8-9. He saw himself as a one-of-a-kind anomaly, openly calling himself “the last” and “the least” of the apostles. To cite from Grudem again:

It seems quite certain that there were none appointed after Paul. When Paul lists the resurrection appearances of Christ, he emphasizes the unusual way in which Christ appeared to him, and connects that with the statement that this was the “last” appearance of all, and that he himself is indeed “the least of the apostles, unfit to be called an apostle” (Grudem, Systematic Theology, 910).

He later adds:

Someone may object that Christ could appear to someone today and appoint that person as an apostle. But the foundational nature of the office of apostle (Eph. 2:20; Rev. 21:14) and the fact that Paul views himself as the last one whom Christ appeared to and appointed as an apostle (“last of all, as to one untimely born,” 1 Cor. 15:8), indicate that this will not happen (Systematic Theology, 911, n. 9)

Because Paul’s apostleship was unique, it is not a pattern that we should expect to see replicated in the church today.

3. Apostolic Authority and the Closing of the Canon

It is our belief that, if we hold to a closed canon, we must also hold to the cessation of the apostolic office.

We turn again to Dr. Grudem for an explanation of the close connection between the apostles and the writing of Scripture:

The New Testament apostles had a unique kind of authority in the early church: authority to speak and write words which were “words of God” in an absolute sense. To disbelieve or disobey them was to disbelieve or disobey God. The apostles, therefore, had the authority to write words which became words of Scripture. This fact in itself should suggest to us that there was something unique about the office of apostle, and that we would not expect it to continue today, for no one today can add words to the Bible and have them be counted as God’s very words or as part of Scripture. (Wayne Grudem, Systematic Theology, 905–906)

Hebrews 1:1–2 indicates that what God first revealed through the Old Testament, He later and more fully revealed through His Son. The New Testament, then, is Christ’s revelation to His church. It begins with His earthly ministry (in the four gospels), and continues through the epistles – letters that were written by His authorized representatives.

Thus, in John 14:26, Christ authorized His apostles to lead the church, promising them that the Helper would come and bring to their remembrance all that Jesus had taught them. The instruction they gave the church, then, was really an extension of Jesus’ ministry, as enabled by the Holy Spirit (cf. Eph. 3:5–6; 2 Pet. 1:20–21). Those in the early church generally understood apostolic instruction as authoritative and as being on par with the OT Scriptures (cf. 1 Thess. 2:13; 1 Cor. 14:37; Gal. 1:9; 2 Pet. 3:16).

To cite from Grudem again, “In place of living apostles present in the church to teach and govern it, we have instead the writings of the apostles in the books of the New Testament. Those New Testament Scriptures fulfill for the church today the absolutely authoritative teaching and governing functions which were fulfilled by the apostles themselves during the early years of the church” (Ibid., 911).

The doctrine of a closed canon is, therefore, largely predicated on the fact that the apostles were unique and are no longer here. After all, if there were still apostles in the church today, with the same authority as the New Testament apostles, how could we definitively claim that the canon is closed?

But since there are no longer apostles in the church today, and since new inscripurated revelation must be accompanied by apostolic authority and approval, it is not possible to have new inscripturated revelation today.

The closing of the canon and the non-continuation of apostles are two concepts that necessarily go hand-in-hand.

4. The Foundational Role of the Apostles

Closely related to the above is the fact that the apostles were part of the foundation period of the church (Eph. 2:20). Since (following the construction metaphor) the foundation stage precedes the superstructure, it is appropriate to infer that the apostles were given to the church for its beginning stages. As Grudem writes, “God’s purpose in the history of redemption seems to have been to give apostles only at the beginning of the church age (see Eph. 2:20)” (Ibid., 911, n. 9).

Our interpretation of “foundation” (as a reference to past period within the church’s history) is strengthened by the evidence from the earliest church fathers. The foundation stage was something the fathers referred to in the past tense, indicating that they understood it as past.

Thus, Ignatius (c. 35–115) in his Epistle to the Magnesians, wrote (speaking in the past tense):

“The people shall be called by a new name, which the Lord shall name them, and shall be a holy people.” This was first fulfilled in Syria; for “the disciples were called Christians at Antioch,” when Paul and Peter were laying the foundations of the Church.

Irenaeus (c. 130–202) in Against Heresies, echoes the past tense understanding that Peter and Paul laid the foundations of the Church (in 3.1.1) and later refers to the twelve apostles as “the twelve-pillared foundation of the church” (in 4.21.3).

Tertullian (c. 155–230), in The Five Books Against Marcion (chapter 21), notes the importance of holding to apostolic doctrine, even in a post-apostolic age:

No doubt, after the time of the apostles, the truth respecting the belief of God suffered corruption, but it is equally certain that during the life of the apostles their teaching on this great article did not suffer at all; so that no other teaching will have the right of being received as apostolic than that which is at the present day proclaimed in the churches of apostolic foundation.

Lactantius (c. 240–320), also, in The Divine Institutes (4.21) refers to a past time in which the foundations of the church were laid:

But the disciples, being dispersed through the provinces, everywhere laid the foundations of the Church, themselves also in the name of their divine Master doing many and almost incredible miracles; for at His departure He had endowed them with power and strength, by which the system of their new announcement might be founded and confirmed.

Other examples could also be added from the later Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers. Chrysostom, for instance, would be another such source (from his Homilies on Ephesians).

The earliest church fathers, from just after the apostolic era, understood the work of the apostles to constitute a unique, “foundational” stage of the church. The fact that they reference this in the past tense, as something distinct from their own ministries, indicates that they understood that the apostolic age had passed, and thus the foundation stage was over.

While the cessation of the apostolic gift/office does not ultimately prove the cessationist case, it does strengthen the overall position – especially in passages like 1 Corinthians 12:28–30, Ephesians 2:20 and 4:11, where apostleship is listed in direct connection with the other charismatic gifts and offices.

5. The Historical Testimony of Those Following the Apostles

In our previous point, we contended that the apostles were given for the foundation stage of the church (Eph. 2:20), and that the early church recognized this foundation stage as a specific time-period that did not continue past the first century.

But it is important to go one step further, and note that the earliest church fathers saw the apostles as a unique group of men, distinct from all who would follow after them.

(A) Those who came after the apostles did not view themselves or their contemporaries as apostles.

According to their own self-testimony, the Christian leaders who followed the apostles were not apostles themselves, but were the “disciples of the apostles” (The Epistle of Mathetes to Diognetus, 11; Fragments of Papias, 5; cf. The Epistle of Polycarp to the Philippians, 6; Ignatius, Against Heresies, 1.10), the elders and deacons of the churches.

Thus, Clement (late first century) in his First Epistle to the Corinthians, 42, notes that:

The apostles have preached the Gospel to us from the Lord Jesus Christ; Jesus Christ [has done so] from God. Christ therefore was sent forth by God, and the apostles by Christ. Both these appointments, then, were made in an orderly way, according to the will of God. Having therefore received their orders, and being fully assured by the resurrection of our Lord Jesus Christ, and established in the word of God, with full assurance of the Holy Ghost, they went forth proclaiming that the kingdom of God was at hand. And thus preaching through countries and cities, they appointed the first-fruits [of their labors], having first proved them by the Spirit, to be bishops and deacons of those who should afterwards believe.

Ignatius, for instance, purposely avoided equating himself with the apostles. Thus, he wrote, “I do not issue commands on these points as if I were an apostle; but, as your fellow-servant, I put you in mind of them” (The Epistle of Ignatius to the Antiochians, 11).

(B) Those who followed the apostles viewed apostolic writings as both unique and authoritative.

Moreover, in keeping with our third point (above), it was “the doctrine of the apostles” (cf. The Epistle of Ignatius to the Magnesians, 13; The Epistle of Ignatius to the Antiochians, 1) that was to be guarded, taught, and heeded. Thus, the “memoirs of the apostles” were held as canonical and authoritative within the early church (cf. Irenaeus, Against Heresies, 2.2.5; Victorinus, Commentary on the Apocalypse, 10.9).

Along these lines, Justin writes:

And on the day called Sunday, all who live in cities or in the country gather together to one place, and the memoirs of the apostles or the writings of the prophets are read, as long as time permits; then, when the reader has ceased, the president verbally instructs, and exhorts to the imitation of these good things (The First Apology of Justin, 67).

The doctrine and writing of the apostles was unique, having been written by the authoritative representatives of Christ Himself.

(C) Those who followed the apostles saw the apostolic age as a unique and unrepeated period of church history.

The fathers saw the “times of the apostles” as a distinct, non-repeateable period of church history (cf. Augustine, On Christian Doctrine, 3.36.54; Reply to Faustus, 32.13; On Baptism, 14.16; et al). Thus, Chrysostom wrote on the uniqueness of fellowship during the apostolic age:

I wish to give you an example of friendship. Friends, that is, friends according to Christ, surpass fathers and sons. For tell me not of friends of the present day, since this good thing also has past away with others. But consider, in the time of the Apostles, I speak not of the chief men, but of the believers themselves generally; “all,” he says, “were of one heart and soul. and not one of them said that aught of the things which he possessed was his own… and distribution was made unto each, according as any one had need.” (Acts 4:32) There were then no such words as “mine” and “thine.” This is friendship, that a man should not consider his goods his own, but his neighbor’s, that his possessions belong to another; that he should be as careful of his friend’s soul, as of his own; and the friend likewise. (Homily on 1 Thess. 1:8-10)

Chrysostom looked back to the deep affection that characterized the apostolic era to provide a contrast to the relative lovelessness of the church in his day. In so doing, he underscores the fact that he understood the apostolic age to be long past. One additional passage might be cited in this regard:

I know that ye open wide your mouths and are amazed, at being to hear that it is in your power to have a greater gift than raising the dead, and giving eyes to the blind, doing the same things which were done in the time of the Apostles. And it seems to you past belief. What then is this gift? charity. (Homily on Heb. 1:6-8)

Many more examples from church history could be given. Eusebius’s whole history is based on the progression of church history from the “times of the apostles” (Ecclesiastical History, Book 8, introduction). Basil, in his work On the Spirit, points to previous leaders from church history (specifically Irenaeus) as those “who lived near the times of the Apostles” (29.72). Tertullian spoke of events that occurred “after the times of the apostles” (The Five Books Against Marcion, 21).

Historical Conclusions

Consistently, the fathers (from the earliest times) mark the apostolic age (and the apostles themselves) as unique. Their writings were regarded as unique and authoritative. Those that followed them were not considered to be apostles. Nor were the times that followed seen as equivalent to the times of the apostles.

Thus we conclude, once again, with Grudem:

It is noteworthy that no major leader in the history of the church – not Athanasius or Augustine, not Luther or Calvin, not Wesley or Whitefield – has taken to himself the title of “apostle” or let himself be called an apostle. If any in modern times want to take the title “apostle” to themselves, the immediately raise the suspicion that they may be motivated by inappropriate pride and desires for self-exaltation, along with excessive ambition and a desire for much more authority in the church than any one person should rightfully have. (Systematic Theology, 911)

A Final Note

Throughout today’s post we have leaned heavily on the work of Wayne Grudem (specifically, his Systematic Theology). This has been intentional for two reasons: (1) he makes excellent, biblically-sound arguments (and we appreciate everything he writes, even if we don’t always agree with his conclusions); and (2) he is a well-known and respected continuationist.

It is significant, in our opinion, that (as a continuationist) he argues so convincingly for the cessation of the apostolic office and the uniqueness of the apostolic age – since this is the very premise upon which the cessationist paradigm is built.

While the cessation of the apostolic gift/office does not ultimately prove the cessationist case, it does strengthen the overall position – especially in passages like 1 Corinthians 12:28–30, Ephesians 2:20 and 4:11, where apostleship is listed in direct connection with the other charismatic gifts and offices.