Article: The Tongues of Angels by Nathan Busenitz (original source here)

Article: The Tongues of Angels by Nathan Busenitz (original source here)

… we are considering the continuationist claim that tongues in the New Testament were not necessarily real human foreign languages. One leading evangelical proponent of this position is Sam Storms, who articulates his views in The Beginner’s Guide to Spiritual Gifts. In this series, we have been responding to the arguments presented by Storms in that book.

In today’s post, we will consider one of the most common arguments for a type of tongues-speech that is non-earthly and non-human in character.

Continuationist Argument 4: The reference to “tongues of angels” in 1 Cor. 13:1 demands the possibility of heavenly (non-earthly) languages.

Sam Storms articulates this argument as follows:

Paul referred to ‘tongues of men and of angels’ (1 Cor. 13:1). While he may have been using hyperbole, he just as likely may have been referring to heavenly or angelic dialects for which the Holy Spirit gives utterance.

I am thankful that Storms (as well as other continuationists like D. A. Carson) allow for the possibility of hyperbole in 1 Corinthians 13:1, because I am convinced from the context that that is exactly how the phrase ought to be understood. Why?

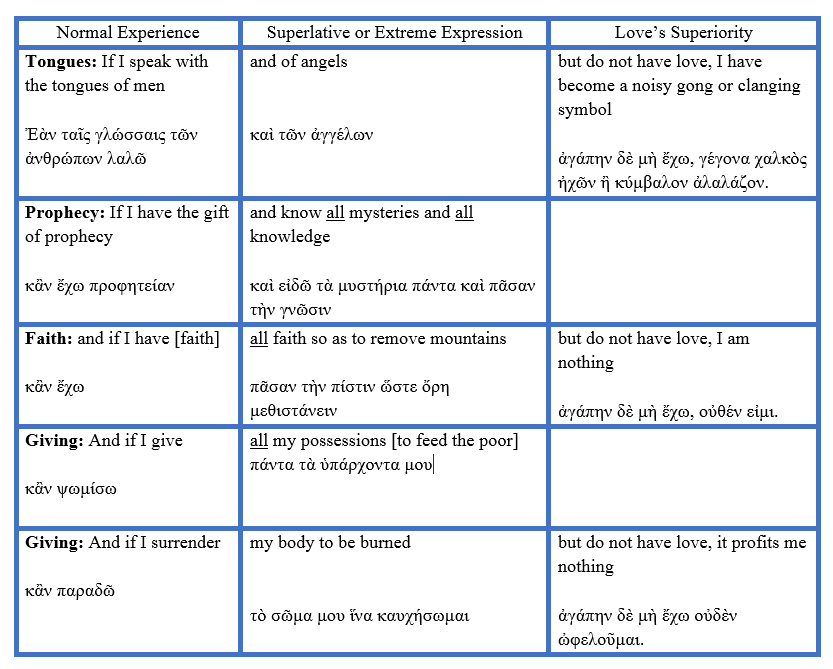

The phrase in 1 Corinthians 13:1 is parallel to Paul’s subsequent statements (in v. 2) of knowing “all mysteries and all knowledge” and of having “all faith so as to [literally] remove mountains.” Both of those statements articulate hyperbolic impossibilities (since no one can know all mysteries or have all knowledge or possess all faith). In verse 3, Paul gives additional extreme examples: giving “away all my possessions” and giving “my body to be burned.” While martyrdom is obviously possible, it still fits the pattern of Paul’s use of extreme examples in order to illustrate a crucial point: even the most superlative expression of any gift (including that which is impossible) would be worthless if it is devoid of love. As John Calvin observed in his commentary on 1 Corinthians 13:1: “When he [Paul] speaks of the tongue of angels, he uses a hyperbolical expression to denote what is singular, or distinguished.”

One of the things that is important to note about the grammar of 1 Corinthians 13:1 is that, in the Greek, it literally reads: “If with the tongues of men I speak and of angels.” That construction is unique and occurs only here in the New Testament. The grammar suggests that Paul intentionally separated the tongues of men from the tongues of angels, articulating the normal expression of the gift of foreign languages before emphatically inserting a hypothetical hyperbole. This pattern is seen in Paul’s subsequent examples as well.

A simple chart shows the parallel between 1 Corinthians 13:1 and Paul’s other superlative statements in the immediate context:

Based on a comparison of all of Paul’s hypothetical examples in 1 Corinthians 13:1-3, a strong case can be made that the apostle was using superlative, hyperbolic, and extreme examples to showcase the superiority of love. This contextual consideration leads us to conclude that the “tongues of angels” was a rhetorical expression, used by Paul to make a point. It did not describe the actual gift of tongues, which consisted only of “the tongues of men.”

However, for the sake of argument, if one insists on taking the phrase “tongues of angels” literally, there are still two important factors to consider:

(1) It represents the rare exception and not the rule, as evidenced by both the unique grammatical construction of 1 Corinthians 13:1 and the other parallel examples Paul included in vv. 2–3. Consequently, this verse cannot be used to establish “angel-speech” as the normal expression of the gift of tongues.

(2) When angels spoke in the Bible, they spoke in a real language that people could understand (cf. Gen. 19; Exod. 33; Joshua 5; Judges 13). Thus, this phrase “tongues of angels” does not support the notion of non-cognitive speech.

It should be noted that some charismatics, including Sam Storms, point to an ancient document called the “Testament of Job” to buttress their case. The Testament of Job was likely written by a group of mystical Jews in Egypt shortly before the time of Christ. It is an apocryphal expansion of the story of Job, and in a couple places it mentions that Job’s daughters sang in the language of the angels.

The assertion is then made that Paul may have been familiar with this apocryphal work and was referencing a similar phenomenon when he wrote 1 Corinthians 13:1.

But there is no reason to assume that Paul was influenced by the Testament of Job or that the Corinthians knew anything about it. Nor is it safe to build our exegetical conclusions on passages from a highly imaginative, mystical, non-Christian, apocryphal account. It is much better to interpret 1 Corinthians 13:1 in its immediate context, as an example of hyperbole used for rhetorical effect to accentuate the superiority of love—rather than insisting that Paul was influenced by a group of heterodox Jewish mystics from Egypt.

When the grammatical and contextual evidence is considered, the “tongues of angels” simply does not provide charismatics with biblical support for a non-human form of tongues.