A series of 4 short articles by Nathan Busenitz (original source thecripplegate.com)

A series of 4 short articles by Nathan Busenitz (original source thecripplegate.com)

Article 1: Are Tongues Real Languages?

We begin today’s post with a question: In New Testament times, did the gift of tongues produce authentic foreign languages only, or did it also result in non-cognitive speech (like the private prayer languages of modern charismatics)? The answer is of critical importance to the contemporary continuationist/cessationist debate regarding the gift of tongues.

From the outset, it is important to note that the gift of tongues was, in reality, the gift of languages. I agree with continuationist author Wayne Grudem when he writes:

It should be said at the outset that the Greek word glossa, translated “tongue,” is not used only to mean the physical tongue in a person’s mouth, but also to mean “language.” In the New Testament passages where speaking in tongues is discussed, the meaning “languages” is certainly in view. It is unfortunate, therefore, that English translations have continued to use the phrase “speaking in tongues,” which is an expression not otherwise used in ordinary English and which gives the impression of a strange experience, something completely foreign to ordinary human life. But if English translations were to use the expression “speaking in languages,” it would not seem nearly as strange, and would give the reader a sense much closer to what first century Greek speaking readers would have heard in the phrase when they read it in Acts or 1 Corinthians. (Systematic Theology, 1069).

But what are we to think about the gift of languages?

If we consider the history of the church, we find that the gift of languages was universally considered to be the supernatural ability to speak authentic foreign languages that the speaker had not learned.

In the early church, the writings of Irenaeus, Hippolytus, Hegemonius, Gregory of Nazianzen, Ambrosiaster, Chrysostom, Augustine, Leo the Great, and others all support this claim. Here are just a few examples:

Gregory of Nazianzus (c. 329–390): “They spoke with foreign tongues, and not those of their native land; and the wonder was great, a language spoken by those who had not learned it. And the sign is to them that believe not, and not to them that believe, that it may be an accusation of the unbelievers, as it is written, ‘“With other tongues and other lips will I speak unto this people, and not even so will they listen to Me” says the Lord’” (The Oration on Pentecost, 15–17).

John Chrysostom (c. 344–407), commenting on 1 Cor. 14:1–2Open in Logos Bible Software (if available): “And as in the time of building the tower [of Babel] the one tongue was divided into many; so then the many tongues frequently met in one man, and the same person used to discourse both in the Persian, and the Roman, and the Indian, and many other tongues, the Spirit sounding within him: and the gift was called the gift of tongues because he could all at once speak divers languages” (Homilies on First Corinthians, 35.1).

Augustine (354–430): “In the earliest times, ‘the Holy Ghost fell upon them that believed: and they spoke with tongues,” which they had not learned, “as the Spirit gave them utterance.’ These were signs adapted to the time. For it was necessary for there to be that sign of the Holy Spirit in all tongues, to show that the Gospel of God was to run through all tongues over the whole earth” (Homilies on the First Epistle of John, 6.10).

In reaching this conclusion, the church fathers equated the tongues of Acts 2 with the tongues of 1 Corinthians 12–14, insisting that in both places the gift consisted of the ability to speak genuine languages.

The Reformers, similarly, regarded the gift of tongues as the supernatural ability to speak real foreign languages. By way of example, here is John Calvin’s treatment of 1 Corinthians 12:10):

John Calvin: “There was a difference between the knowledge of tongues, and the interpretation of them, for those who were endowed with the former [i.e. the gift of tongues] were, in many cases, not acquainted with the language of the nation with which they had to deal. The interpreters rendered foreign tongues into the native language. These endowments they did not at that time acquire by labor or study, but were put in possession of them by a wonderful revelation of the Spirit.” (Commentary on 1 Cor. 12:10)

To the names of the Reformers, we could add the names of the Puritans, and the names of theologians like Jonathan Edwards, Charles Hodge, Charles Spurgeon, and B.B. Warfield among many others.

Even Charles Fox Parham, the founder of modern Pentecostalism, was absolutely convinced that the biblical gift of tongues consisted of the supernatural ability to speak in human foreign languages that the speaker had never learned. When he and his students initially experienced the modern gift of tongues, they thought it consisted of real human languages. Parham stated his position clearly in a number of newspapers at the time. (These quotes come from chapter 2 of John MacArthur’s Strange Fire.)

Charles Parham cited in the Topeka State Journal, January 7, 1901: “The Lord will give us the power of speech to talk to the people of the various nations without having to study them in schools.”

Charles Parham cited in the Kansas City Times, January 27, 1901: “A part of our labor will be to teach the church the uselessness of spending years of time preparing missionaries for work in foreign lands when all they have to do is ask God for power.”

Charles Parham cited in the Hawaiian Gazette, May 31, 1901: “There is no doubt that at this time they will have conferred on them the ‘gift of tongues,’ if they are worthy and seek it in faith, believing they will thus be made able to talk to the people whom they choose to work among in their own language, which will, of course, be an inestimable advantage. The students of Bethel College do not need to study in the old way to learn the languages. They have them conferred on them miraculously . . . [being] able to converse with Spaniards, Italians, Bohemians, Hungarians, Germans, and French in their own language. I have no doubt various dialects of the people of India and even the language of the savages of Africa will be received during our meeting in the same way. I expect this gathering to be the greatest since the days of Pentecost.”

Parham, and his students, were convinced by their study of the New Testament that the gift of tongues consisted of the miraculous ability to speak in human foreign languages that the speaker had not learned. But there was one major problem. The tongues-speech of Parham and his students quickly proved to be something other than human foreign languages. In the words of charismatic authors Jack Hayford and David Moore:

Sadly, the idea of xenoglossalalic tongues [i.e. foreign languages] would later prove an embarrassing failure as Pentecostal workers went off to mission fields with their gift of tongues and found their hearers did not understand them. (The Charismatic Century, 42).

Other historians report the disappointment faced by early Pentecostals when it became clear that their tongues did not consist of authentic foreign languages:

S. C. Todd of the Bible Missionary Society investigated eighteen Pentecostals who went to Japan, China, and India “expecting to preach to the natives in those countries in their own tongue,” and found that by their own admission “in no single instance have [they] been able to do so.” As these and other missionaries returned in disappointment and failure, Pentecostals were compelled to rethink their original view of speaking in tongues. (Robert M. Anderson, Vision of the Disinherited, 90–91)

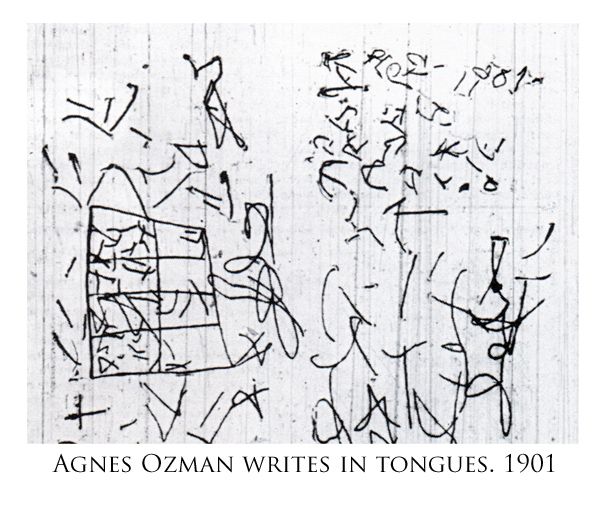

It might be worth noting that these early Pentecostals not only spoke in tongues, they also wrote in tongues. And some of these early tongues writings were published by local newspapers. Agnes Ozman, one of Parham’s students, was the first to speak in tongues on January 1, 1901. She reportedly spoke in the Chinese language, thereby launching the Pentecostal Movement. Ozman also claimed to write in Chinese. The picture at the top of this article showcases her work.

When it became apparent that the Pentecostal understanding of tongues did not consist of human languages, the entire movement was faced with an interesting dilemma. They could uphold their exegetical understanding of tongues and deny their experience. Or, they could hold on to their experiential understanding of tongues and radically change their exegesis. They chose the latter. And thus, a new understanding of the nature of the gift of tongues emerged out of twentieth-century Pentecostal experience.

To be fair, modern charismatics acknowledge the possibility that tongues can sometimes be foreign languages. They point to anecdotal evidence in an effort to claim that on rare occasions foreign languages might be spoken by a modern tongues-speaker. But those anecdotes do not hold up under scrutiny. As D. A. Carson rightly observes:

“Modern tongues are lexically uncommunicative and the few instances of reported modern xenoglossia [speaking foreign languages] are so poorly attested that no weight can be laid on them” (Showing the Spirit, 84).

When professional linguists study modern glossolalia (tongues-speech), they come away convinced that contemporary tongues bear no resemblance to true human language. After years of extensive research, University of Toronto linguistics professor William Samarin concluded:

Glossolalia consists of strings of meaningless syllables made up of sounds taken from those familiar to the speaker and put together more or less haphazardly. The speaker controls the rhythm, volume, speed and inflection of his speech so that the sounds emerge as pseudolanguage—in the form of words and sentences. Glossolalia is language-like because the speaker unconsciously wants it to be language-like. Yet in spite of superficial similarities, glossolalia fundamentally is not language. (cited from Joe Nickell, Looking for a Miracle, 108)

This brings us back to the question we asked at the beginning. Has the church, historically, been right to conclude that the gift of tongues in the New Testament consists of the supernatural ability to speak in foreign languages previously unknown to the speaker? Or is the modern charismatic movement right to conclude that the gift of tongues encompasses something other than cognitive foreign languages?

Over the next few weeks, I hope to address this issue by specifically considering the arguments made by continuationist author Sam Storms, in his 2012 book, The Beginner’s Guide to Spiritual Gifts. There Storms argues for the validity of modern charismatic glossolalia. In so doing, he provides nine reasons why he believes tongues need not be human languages.

We will interact with each of his reasons in the posts to follow.

2: Sam Storms and Two Types of Tongues

In last week’s post, we introduced a series about the gift of tongues. Cessationists generally define the gift of tongues as the supernatural ability to speak authentic foreign languages that the speaker had not previously learned. Continuationists, by contrast, generally allow for the possibility that the gift produces speech that does not correspond to any human language. The question we are asking in this series is whether or not that possibility is biblically warranted.

Does the Gift of Tongues Produce Non-Human Languages?

Most continuationists acknowledge that modern tongues-speech predominately consists of something other than human foreign languages.

Of course, some continuationists point to anecdotal evidence to claim that modern glossolalia (tongues-speaking) can sometimes consist of human languages. But even supporters of modern tongues, like George P. Wood of the Assemblies of God, admit the infrequency of such reported occurrences. After commenting on alleged accounts “where one person spoke in a tongue that a second person recognized as a human language,” Wood is quick to state: “Admittedly, such occurrences are rare” (from his review of Strange Fire, published Jan. 13, 2014).

Such occurrences are so rare, in fact, that continuationist claims about modern glossolalia producing real human languages remain unconvincing to everyone outside the charismatic movement (including both Christians and non-Christians). As we saw in the previous post, professional linguists (like William Samarin of the University of Toronto) who study glossolalia have concluded that it “fundamentally is not language.” D. A. Carson, himself a non-cessationist, represents an objective assessment of the evidence when he writes: “Modern tongues are lexically uncommunicative and the few instances of reported modern xenoglossia [speaking foreign languages] are so poorly attested that no weight can be laid on them” (Showing the Spirit, 84).

The evidence, or lack thereof, leaves continuationists like Sam Storms in the necessary position of contending that modern tongues-speaking is legitimate, even if it does not consist of genuine human languages. According to Storms, the gift of tongues in New Testament times did not always express itself in human language either. In his 2012 book, The Beginner’s Guide to Spiritual Gifts, Storms gives nine reasons why tongues were not necessarily human languages. His arguments are typical of other continuationist authors, and as such provide a representative sampling of the continuationist position.

Storms’ chapter on tongues (chapter 9 in the book) begins by asking the very question we are asking in this blog series. He writes, “Are tongues human languages? This is a key question for those who say the gift of tongues has ceased for today” (p. 179). After distinguishing the cessationist position from that of the continuationist, Storms reiterates the heart of the issue: “Is it true that ‘all tongues in the New Testament were human language’?” (ibid.).

Storms, of course, answers that question in the negative, which brings us to his first reason for concluding that tongues in the New Testament were not necessarily human languages.

Continuationist Argument 1: The manifestation of tongues described in Acts 2 is not the only kind of tongues described in the New Testament.

There is no question that the tongues in Acts 2 consisted of authentic foreign languages. Luke states, in Acts 2:4), “And they were all filled with the Holy Spirit and began to speak with other tongues, as the Spirit was giving them utterance.” Luke continues in vv. 9–11 to list some 16 different languages and dialects that were spoken.

Storms readily admits that the tongues described in Acts 2 were human foreign languages. But he proceeds to argue that this is the only place in the New Testament where that was true. To quote Storms:

Acts 2 is the only text in the New Testament where tongues-speech consists of foreign languages not previously known by the speaker. This is an important text, yet there is no reason to think Acts 2, rather than, say, 1 Corinthians 14, is the standard by which all occurrences of tongues-speech must be judged (p. 180).

Storms’ view—that there are two types of tongues in the New Testament (only one of which consisted of human languages)—is fairly common among continuationists. As Adrian Warnock once explained on his blog: “One thing that most of us [continuationists] agree on is that there are different kinds of tongues. . . . I think it is fair to say that the tongues of 1 Corinthians are different from those of Acts 2.”

But does the biblical evidence allow for this distinction? More specifically, is the gift of tongues in 1 Corinthians categorically different than the gift described in Acts? I certainly don’t believe so.

Here are seven observations from the biblical text that indicate the gift of tongues is the same in both Acts and 1 Corinthians:

1. Same Terminology: In both Acts and 1 Corinthians 12–14, the same words are used to describe the gift of tongues. Both Luke and Paul repeatedly describe the phenomena using the combination of laleo (“to speak”) and glossa (“languages”) (Acts 2:4, 11; 10:46; 19:6; 1 Cor. 12:10, 28; 13:1, 8; 14:2, 4), 5, 9, 13, 18, 19, 22, 23, 26, 27, 39).

2. Same Description (as languages): In both Acts and 1 Corinthians 12–14, the gift of tongues is directly associated with foreign languages. In Acts 2, foreign languages are clearly in view, and Luke lists a number of them in vv. 9–11. In 1 Corinthians 14:10–11, Paul associates tongues with the “many kinds of languages in the world.” Moreover, Paul’s reference to Isaiah 28:11–12 in 1 Cor. 14:21 supports the notion that he has foreign languages in mind.

We might add that the gift of interpretation confirms that the nature of tongues in 1 Corinthians consisted of authentic foreign languages (cf. 1 Cor. 12:10; 14:5, 13). On the day of Pentecost, Jewish pilgrims from various parts of the world did not need an interpreter to understand the languages that were being spoken. But in the congregation in Corinth, an interpreter was needed so that anyone who did not understand the language being spoken could be edified. As Norman Geisler explains: “The fact that the tongues of which Paul spoke in 1 Corinthians could be ‘interpreted’ shows that it was a meaningful language. Otherwise it would not be an ‘interpretation’ but a creation of the meaning. So the gift of ‘interpretation’ (1 Corinthians 12:30; 14:5, 13) supports the fact that tongues were a real language that could be translated for the benefit of all by this special gift of interpretation.”

3. Same Source (the Holy Spirit): In both Acts and 1 Corinthians 12–14, the gift of tongues was given by the Holy Spirit. The miraculous tongues in Acts were directly related to the working of the Holy Spirit (2:4, 18; 10:44–46; 19:6). In fact, tongue-speaking is evidence of having received the “gift” (dorea) of the Holy Spirit (10:45). As in Acts, the gift of tongues in 1 Corinthians was directly related to the working of the Holy Spirit (12:1, 7, 11, etc.). Similarly, the gift of tongues is an evidence (or “manifestation”) of having received the Holy Spirit (12:7).

4. Same Recipients (both apostles and non-apostles): In both Acts and 1 Corinthians 12–14, the gift of tongues was experienced by both apostles and non-apostles. On the Day of Pentecost it involved all of those gathered in the Upper Room. In Acts 11:15–1 (and 15:8), Peter explains that the experience of Acts 10 was the same as that of Acts 2, even noting that Cornelius and his household had received the same gift as the apostles on the Day of Pentecost. In 1 Corinthians, Paul, as an apostle, possessed the gift of tongues (14:18). Yet he recognized that there were non-apostles in the Corinthian church who also possessed the gift.

5. Same Sign (to unbelievers): In both Acts and 1 Corinthians 12–14, the gift of tongues was given as a sign to the nation of Israel that God was now working through the Jew-Gentile church. In Acts, it is presented as a sign for unbelieving Jews (2:5, 12, 14, 19). In 1 Corinthians, as in Acts, the gift of tongues was a sign for unbelieving Jews (14:21–22; cf. Is. 28:11). Thus, the Corinthian use of tongues was a sign just as the apostles’ use of tongues was a sign on the day of Pentecost.

6. Same Connection (to prophecy): In the book of Acts, the gift of tongues is closely connected with prophecy (2:16–18; 19:6) and with other signs that the apostles were performing (2:43). In 1 Corinthians, as in Acts, the gift of tongues is closely connected with prophecy (all throughout 12–14). Interestingly, continuationists contend that the gift of prophecy in Acts is the same as the gift of prophecy in 1 Corinthians. Only the gift of tongues gets redefined.

7. Same Reaction (from unbelievers): In Acts 2, some of the unbelieving Jews at Pentecost accused the apostles of being drunk when they heard them speaking in other tongues (foreign languages which those particular Jews did not understand). Similar to Acts, in 1 Corinthians, Paul states that unbelievers will accuse the Corinthians of being mad [not unlike “drunk”] if their tongues are not interpreted (14:23), and are therefore not understood by the hearer.

Also: Added to this is the fact that Luke (the author of Acts) was a close associate of Paul (the writer of 1 Corinthians), and wrote under Paul’s apostolic authority. Moreover, the book of Acts was written after the first epistle to the Corinthians. It is unlikely, then, that Luke would have used the exact same terminology as Paul if he understood there to be an essential difference between the two gifts (especially since such could lead to even greater confusion about the gifts — a confusion which plagued the Corinthian church).

And: There is also the issue of sound hermeneutics: In interpreting the Bible, we use the clearer passage to help us understand the less-clear passage. In this case Acts 2 is the clearer passage. So it is appropriate to allow our understanding of Acts to inform our interpretation of 1 Corinthians. Author Gerhard Hasel put it this way:

There is but one clear and definitive passage in the New Testament which unambiguously defines “speaking in tongues” and that is Acts 2. If Acts 2 is allowed to stand as it reads, then “tongues” are known, intelligible languages, spoken by those who received the gift of the Holy Spirit and understood by people who came from the various areas of the ancient world to Jerusalem. We may raise a question of sound interpretation. Would it not be sound methodologically to go from the known definition and the clear passage in the New Testament to the less clear and more difficult passage in interpretation? Should an interpreter in this situation attempt to interpret the more difficult passage of 1 Cor 12–14 in light of the clearer passage of Acts 2? Is this not a sound approach?

And, as we noted in last week’s post, the church historically equated the tongues of Acts with the tongues of Corinth.

Conclusion: The biblical (and historical) evidence leads us to conclude that there is only one gift of tongues, and (based on its description in Acts 2) it consisted of authentic foreign languages that the speaker had not previously learned (Mark 16:17; Acts 2:4, 8–11; 10:47; 11:17). Storms’ claim that the tongues of Acts 2 were categorically different than the tongues of 1 Corinthians falls short.

To quote again from D. A. Carson:

If [Paul] knew of the details of Pentecost (a currently unpopular opinion in the scholarly world, but in my view eminently defensible), his understanding of tongues must have been shaped to some extent by that event. Certainly tongues in Acts exercise some different functions from those in 1 Corinthians; but there is no substantial evidence that suggests Paul thought the two were essentially different. We have established high probability, I think, that Paul believed the tongues about which he wrote in 1 Corinthians were cognitive. (Showing the Spirit, 83).

Such a conclusion has significant ramifications for contemporary charismatics: when they acknowledge that the modern form of tongues-speaking does not involve actual foreign languages, they are simultaneously acknowledging that their contemporary experience does not have any New Testament precedent.

3. Did Cornelius Speak in Non-human Languages?

What are believers today to think about the gift of tongues?

D. A. Carson asks that question in his book, Showing the Spirit. On pages 84–85, he writes:

How … may tongues be perceived? There are three possibilities: [1] disconnected sounds, ejaculations, and the like that are not confused with human language; [2] connected sequences of sounds that appear to be real languages unknown to the hearer not trained in linguistics, even though they are not; [3] and real language known by one or more of the potential hearers, even if unknown to the speaker. . . . Our problem so far is that the biblical descriptions of tongues seem to demand the third category, but the contemporary phenomena seem to fit better in the second category; and never the twain shall meet.

Storms_GuideAs Carson helpfully articulates, contemporary tongues “appear to be real languages . . . even though they are not.” By contrast, biblical tongues consisted of “real language known by one or more of the potential hearers, even if unknown to the speaker.”

But if biblical tongues consisted of real human languages (i.e. a real language known by one or more of the potential hearers), then how can modern continuationists advocate tongues-speech that produces nothing more than the appearance of language? (Those interested in Carson’s unique solution to this dilemma can find it here.)

In his book The Beginner’s Guide to Spiritual Gifts, author Sam Storms — like most continuationists — attempts to answer that dilemma by giving a list of reasons why he believes the New Testament gift of tongues did not necessarily produce real human languages. If he can show that biblical tongues were not always actual languages, he can demonstrate a precedent for the modern gift of tongues. We addressed his first reason in last week’s post. Today we will consider his second argument.

Continuationist Argument 2: The tongues of Acts 10 and 19 were of a different kind than the tongues of Acts 2.

One of the essential tenets of Storms’ position is that Acts 2 (where tongues were clearly real foreign languages) represents an exception, and not the norm. Storms is explicit on this point. He writes:

Acts 2 is the only text in the New Testament where tongues-speech consists of foreign languages not previously known by the speaker. This is an important text, yet there is no reason to think Acts 2, rather than, say, 1 Corinthians 14, is the standard by which all occurrences of tongues-speech must be judged. (emphasis added)

Even in the book of Acts, he seeks to drive a wedge between the tongues of Acts 2 and the tongues of Acts 10 and 19. Storms phrases his case this way:

If tongues-speech is always in a foreign language intended as a sign for unbelievers, why are the tongues in Acts 10 and Acts 19 spoken in the presence of only believers?

In essence, Storms’ argument here is that because the audiences in Acts 10 and 19 were different than the audience in Acts 2, then the nature of the tongues spoken on those various occasions must have been different too.

But it is difficult to see how this argument actually supports the notion of a non-human-language form of tongues. After all, cessationists would readily agree that the immediate audiences of Acts 2, 10, and 19 were different. But they would insist that the tongues spoken on all three occasions consisted of authentic foreign languages previously unlearned by the speakers. In other words, the essence of the phenomenon did not change even if the immediate audience did.

Storms describes the tongues-speech of Acts 2 as that which was “intended as a sign for unbelievers.” He sees that distinction as a key difference between the tongues of Acts 2 and the tongues of Acts 10, 19, and 1 Corinthians 12–14. Based on that distinction, he places the foreign languages of Acts 2 in a separate category from those other New Testament texts. Yet, the force of Storms’ argument at this point is overturned by the words of 1 Corinthians 14:22), where Paul explicitly states that the tongues being spoken in the Corinthian church were also “a sign for unbelievers.”

Moreover, it is not difficult to see how the tongues of Acts 10, for example, served as a sign to the apostate nation of Israel by marking the inclusion of Gentiles into the church. Speaking of the tongues at Pentecost (in Acts 2), John MacArthur explains,

The blessing of that sign [of foreign languages] was that God would build a new nation of Jews and Gentiles to be His people (Gal. 3:28), to make Israel jealous and someday repent (see Rom. 11:11–12, 25–27). The sign was thus repeated when Gentiles were included in the church (Acts 10:44–46). (John MacArthur, First Corinthians Bible Study Guide, 36).

But were the tongues of Acts 10 and 19 something categorically different than the tongues of Acts 2? Did Cornelius and his family utter speech that only appeared to be a language, but really wasn’t? Or did they speak in authentic foreign languages as had happened years earlier to the Jewish believers at Pentecost?

Evidence from the book of Acts confirms that the tongues of Acts 10 and 19 represent the same phenomena as the tongues of Acts 2. For starters, the terminology Luke uses to describe all three events is the same—a combination of “laleo” with “glossa” (in Acts 2:4, 10:46, and 19:6). Luke clearly defines what he means by those terms in Acts 2 (i.e. speaking foreign languages). Nothing in either Acts 10 or Acts 19 suggests that he suddenly and inexplicably changed that definition later in his narrative.

Furthermore, Peter expressly states that the phenomenon experienced at Cornelius’ house in Acts 10 was the same as the experience in Acts 2. In Acts 11:15–17(cf. 15:8), Peter told the Jewish believers in Jerusalem:

And as I began to speak, the Holy Spirit fell upon them just as He did upon us at the beginning. And I remembered the word of the Lord, how He used to say, ‘John baptized with water, but you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit.’ Therefore if God gave to them the same gift as He gave to us also after believing in the Lord Jesus Christ, who was I that I could stand in God’s way?

It was only after the Jewish Christians heard that these Gentiles had received the Holy Spirit in the same way as those at Pentecost that they were willing to accept them into the church. As Luke writes in verse 18, “When they heard this, they quieted down and glorified God, saying, ‘Well then, God has granted to the Gentiles also the repentance that leads to life.’”

If the Gentiles of Acts 10 had experienced something categorically different than what Jewish believers experienced on the Day of Pentecost, the Jewish Christians in Jerusalem would have remained reluctant to embrace them into the church. But because their experience was the same, it was obvious to all that the Holy Spirit was, in fact, welcoming Gentiles into the church.

In light of Peter’s clear statement, there is no reason to assume that the tongues of Acts 10 (and by extension Acts 19) were categorically different than the tongues of Acts 2. Consequently, most continuationists retreat to the book of 1 Corinthians in order to make their case for a second category of non-human glossolalia. (This is, in fact, where Sam Storms develops most of his arguments.) Over the next few weeks, we will consider key texts from 1 Corinthians, such as 12:10, 13:1, and 14:2.

Today, however, our focus has centered on the book of Acts. Based on Luke’s consistent use of key terms and Peter’s clear testimony, there is no compelling reason to abandon the historic understanding of Acts 10 and 19—namely, that the tongues spoken in those chapters consisted of real foreign languages, just like the tongues of Pentecost in Acts 2.

If that is true, then Storms’ premise (that Acts 2 is the only text where tongues-speech consisted of authentic foreign languages) is shown to be false.

4: Various Kinds of Tongues

In particular, we are considering the continuationist claim that tongues in the New Testament did not always consist of real human foreign languages. Wayne Grudem, in Making Sense of the Church, represents the continuationist position when he writes:

“Are tongues known human languages then? Sometimes this gift may result in speaking in a human language that the speaker has not learned, but ordinarily it seems that it will involve speech in a language that no one understands, whether that be a human language or not” (emphasis added).

In his book, The Beginner’s Guide to Spiritual Gifts, continuationist author Sam Storms echoes that same thesis, insisting that “Acts 2 is the only text in the New Testament where tongues-speech consists of foreign languages not previously known by the speaker.” Storms’ assumption is that, even in the New Testament, the majority of tongues speech consisted of something other than human language.

Storms marshals nine arguments to defend that assumption. We have already considered his first two arguments (in the previous two posts). Today we will consider a third.

Continuationist Argument 3: First Corinthians 12:10 states that there are different kinds of tongues, therefore not all tongues are human languages.

In 1 Corinthians 12:8–10 Paul writes,

For to one is given the word of wisdom through the Spirit, and to another the word of knowledge according to the same Spirit; to another faith by the same Spirit, and to another gifts of healing by the one Spirit, and to another the effecting of miracles, and to another prophecy, and to another the distinguishing of spirits, to another various kinds of tongues, and to another the interpretation of tongues.

Because Paul says that there are “various kinds of tongues,” continuationists assert that this means there are at least two categories of tongues speech: human (earthly) languages and non-human (heavenly) languages. Storms articulates the argument like this:

Note also that Paul describes various kinds [or ‘species’] of tongues (gene glosson) in 1 Corinthians 12:10. It is unlikely that he means a variety of different human languages, for who would ever have argued that all tongues were only one human language, such as Greek or Hebrew or German? His words suggest that there are different categories of tongues-speech, perhaps human languages and heavenly languages.

Based on that interpretation, Storms believes 1 Corinthians 12:10 provides exegetical support for the notion that tongues can be something other than human languages.

So what are we to make of the phrase “various kinds of tongues”? Is Paul differentiating between two fundamentally different categories of tongues (as Storms and other continuationists contend)? Does this verse really distinguish between earthly (human) languages on the one hand, and heavenly (non-human) languages on the other?

I certainly don’t think so.

Here are four reasons why:

1) First, though not a major point, it should be noted that the word “various” is not in the Greek. Literally, Paul says, “to another, kinds of tongues” (etero gene glosson). Thus, no interpretative emphasis should be placed on the English word “various” or “different.” If continuationists are going to make their case from this verse, it cannot come from that word.

2) Second, though the phraseology is slightly different, when Luke speaks of “other tongues” (eterais glossais) in Acts 2:4, no one suggests that he had in mind fundamentally different categories of language (e.g. human vs. non-human dialects). Rather, as Acts 2:8–11 makes clear, the “other tongues” simply referred to a variety of human foreign languages. In fact, Luke lists 16 distinct foreign dialects in that text. (And, as we have already discussed, there are compelling reasons to see the tongues of Acts 2 as ontologically equivalent to the tongues of 1 Corinthians 12–14).

3) Third, the Greek word genos (or gene in 1 Cor. 12:10) means “kind” in the sense of “family,” “race”, “people,” “nation” or “offspring” (cf. Gal. 1:14; Phil. 3:5O; 2 Cor. 11:26; Acts 7:19; 1 Pet. 2:9). It is the Greek word from which our English word genus (and words like genetics and genealogy) is derived. In this context, the most natural understanding of genos refers to various families of languages. As John MacArthur points out about this verse, “Linguists often refer to language ‘families’ or ‘groups,’ and that is precisely Paul’s point: there are various families of languages in the world, and this gift enabled some believers to speak in a variety of them” (Strange Fire, 141).

4) Fourth, and perhaps most significantly, Paul uses gene just two chapters later (in 1 Corinthians 14) to clearly refer to various kinds of earthly, human languages. In 1 Corinthians 14:10–11, Paul writes:

There are, perhaps, a great many kinds of languages [gene phonon] in the world, and no kind is without meaning. If then I do not know the meaning of the language, I will be to the one who speaks a barbarian, and the one who speaks will be a barbarian to me.

Here again, Paul uses the exact same word for “kinds” (gene) as he did in 1 Cor. 12:10. This time, he pairs it with a synonym of glosson (“tongues” or “languages”), using the word phonon (“sounds” or “languages”). The phrases gene glosson (12:10) and gene phonon (14:10) are grammatically identical and lexically synonymous. All commentators, including continuationists, acknowledge that the phrase “kinds of languages” in 14:10 refers only to that which is human or earthly. The phrase “in the world” makes that conclusion inescapable. Hence, even within the context of 1 Corinthians 12–14, we have at least one unquestionable example of Paul using gene (“kinds”) to refer to various families of human languages.

In 12:10, when Paul uses the very same word for “kinds,” continuationists insist that Paul must mean something other than various families of human language. But they do this contrary to the natural meaning of the Greek word genos, and contrary to Paul’s own usage of that word in 14:10. Coupled with Luke’s description of “tongues” in Acts 2, which we have already contended parallels Paul’s understanding in 1 Corinthians, the continuationist’s interpretation of 1 Corinthians 12:10 becomes difficult to maintain.

The much more natural reading of 1 Corinthians 12:10 is to see it as parallel to 1 Corinthians 14:10. There are many kinds of languages in the world, and the gift of tongues was the Spirit-given ability to speak fluently in one or more of those foreign languages (even though they were previously unknown to the speaker). Such an interpretation may not match up with the modern tongues of the contemporary charismatic movement, but it fits perfectly with the tongues of Pentecost as described in Acts 2.

*A 5th article – on the subject of the tongues of angels can be found here.