While I do not hold to pre-millennialism (as stated below) this is an excellent article by Pastor Anthony Wood of Mission Bible Church, Tustin, California, regarding doctrinal unity (original source here).

While I do not hold to pre-millennialism (as stated below) this is an excellent article by Pastor Anthony Wood of Mission Bible Church, Tustin, California, regarding doctrinal unity (original source here).

Evangelicals Can Have Doctrinal Discussion in a God Honoring Way

“We must know when to wield the sword mightily and when to keep it sheathed!” prince of preachers Charles Spurgeon once exclaimed.

On Twitter we find two types of evangelical Christian… One group steers clear of any biblical truth that may challenge or offend. The second type tends to live in a polemic bubble of red cap and exclamation mark. One day we’ll die on the hill. The next day we post jelly memes and dandelion post cards. This is true of us pastors too. At times we may even live in one camp for a day and then cross over. However, there are some prudent things we can do to prevent from virtualized doctrinal schizophrenia.

First, we shouldn’t be so hard on the concept of multiple denominations. One sad hallmark of modern evangelicalism is the tendency to get frustrated by the idea of denominations. Many who are new to the faith ponder why there are so many different versions of Christianity. However, what they miss is that denominationalism, although not perfect, is better than what existed before it! Up until the reformation, Christians had no choice but to participate in the papal system of Roman Catholicism. If they refused, they could be killed as dissenters.

Even the Anglican Church attempted to force conformity up until the 1680’s when the birth of pilgrims in a new nation (America) provided the right to disagree and depart based on matters of faith. As early as the Westminster Assembly (1642-1649) independents were pushing “congregational” principles, including the following statements:

1) Due to man’s inability to fully comprehend truth, differences about the outward form of church are inevitable.

2) Differences may not involve fundamentals of the faith but they are important and a Christian is obligated to practice what he believes the Bible teaches.

3) Because no church has a final and full grasp on divine truth, the true Church of Christ can never be fully represented by one single ecclesiastical structure.

4) Separation does not itself constitute schism, it’s possible to divide at many points and still be Christian.

We take these items for granted but they were world-changing in 1640. Historian Bruce Shelley summarizes the role America played in denominationalism:

“The religious diversity of the American colonies called for a new understanding of the church. We may call it the denominational theory of the church. Denominationalism, as originally designed, is the opposite of sectarianism. A sect claims the authority of Christ for itself alone. It believes that it is the true body of Christ; all truth belongs to it and no other religion. So by definition a sect is exclusive. The word denomination by contrast was an inclusive term. It implied that the Christian group called or denominated by a particular name was but one member of a larger group – the church – to which all denominations belong. The denominational theory of the church, then, insists that the true church cannot be identified with any single ecclesiastical structure. No denomination claims to represent the whole church of Christ. Each simply constitutes a different form – in worship and organization – of the larger life of the church.”[1]

One of the powerful opportunities both the reformation and pilgrimage to America gave Christianity was freedom to have true scholarly discussion about the Bible without risking life and limb! And, this should convict us… Instead of taking our freedoms for granted we must take full advantage, properly defining what we believe and how we will practice it. And, we must be prepared to sit and discuss what we’ve learned with our neighbors in Christ, regardless of what church they have attended previous.

Many modern evangelicals have a real aversion to doctrinal discussion. There are two reasons for this. First, they live in a culture promoting “tolerance” and have been taught that disagreement is wrong. Second, they don’t know their doctrine because they’ve been raised to “feel” and not to think. These two issues go hand in hand, a person who doesn’t think, doesn’t know how to disagree, and a person unwilling to disagree, has never been forced to think. Sadly, this creates a culture of whims, emotions, and experientialism.

Let me say for the record: You can learn the Word of God and you must learn the word of God! Whether you are a parishioner, Sunday school teacher, young man beginning out in ministry, or preacher still using the pulpit for fantasy and fairy tale, you still have time to learn how to “rightly divide” truth. I promise that will never find more confidence in this life then starting out a day knowing your position in Christ and having His word overflow from your heart to the tip of your tongue!

However, there is an equal and opposite reaction that I also must warn you against: It is the tendency to share truth with the wrong motive. As we grow in understanding of the Word, we can become puffed up in knowledge, and forget about love. In some cases, we can promote truth, but do so with a heart that aims to destroy, instead of to save. We’ve all seen the large red caps on an email or the “click bait” on a Facebook post about death, hell, and taxes. The goal of Christian truth is to glorify God not look tough.

So, how do we balance bold truth and a heart of patience? How do we engage people online? How do we discern who is part of the body of Christ versus who is a pretender? How do we engage lovingly with seekers or the immature in our own congregation? The first step is knowing which biblical doctrines are foundational to Christianity versus those which have long been debated. Once we have come to some basic conclusions about essential versus non-essentials we’ll be able to discern how best to dialogue.

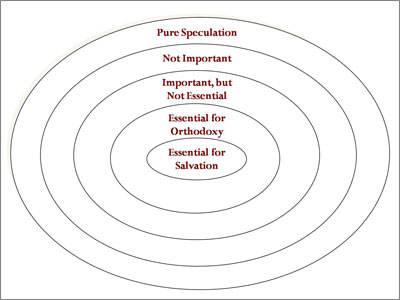

To begin, let’s look at the chart below. In the chart, orthodox doctrines absolutely critical to the Christian faith make up the center (doctrines that “save” versus those that do not save), while doctrines of health and practice are in the outer circles. Finally, doctrines that are important but not integral to gospel clarity, stand at the outermost. In essence, the interior circles define major doctrines of historic church life while the third circle defines important doctrines of church practice. Items in the fourth circle and beyond define “minor” doctrines of church training which can cause academic tension but aren’t normally pain-points for an average congregant. The word “minor” is in quote because I’ve used it in descriptive sense only, understanding man does not retain the right to de-prioritize Scripture (Matt 5:19). Also, I’m very aware that systematically, every doctrine impacts another in some sense, thus marking the critical nature of the pastorate in every local church.

Chart 1.2 Circles of Orthodoxy

Chart 1.2 Circles of Orthodoxy

Inside the circles titled “Essential for Salvation” and “Essential for Orthodoxy” the following doctrines are historically accepted as foundational to Christianity, providing fences of fellowship for the true universal body of Christ. It is understood that within each category there are sub-variants but an acceptance of the overarching premise is mandatory. In essence, these are truths that depict whether someone is Christian or not:

Biblical Authority. A true Christian will hold that the Bible is the divinely inspired and inerrant Word of God, an objective revelation from God to man, entirely authoritative, constituting the only infallible rule of faith and practice. We believe this because the writings of Paul verified the Gospel authors, who verified Christ, who verified the OT Scriptures, all of which were supported and canonized by the Patristic fathers in early church history. [John 10:33-36, 1 Corinthians 2:13, 2 Tim 3:15-17, 2 Peter 1:20-21]

Virgin Birth. A true Christian will hold that Jesus Christ, the living Word, became flesh through His miraculous conception by the Holy Spirit and virgin birth. We believe this because the entire Gospel testimony, and Christianity itself, rests on Jesus Christ being an unblemished Son of God who takes away the sins of the world. [Matthew 1:23, John 1:14, 1 John 4:9]

Deity of Christ. A true Christian will hold that Jesus Christ is the unique Son of God, born of a virgin, representing deity and humanity in indivisible oneness, existing for eternity past and eternity future, so that He may reveal God and redeem men. We believe this because Jesus Himself testified to the matter and if not fully God He is no proper substitute for sin, while if not fully man He is unable to identify with temptation and act as High Priest [John 5:23, John 10:36-38, John 14:9-10, Hebrews 4:14-16, 1 Peter 1:18-19]

Substitutionary Atonement. A true Christian will hold that Christ died in the place of men, for their sins, the efficacy of this death freeing the believing sinner from the punishment, penalty, power, and one day presence of sin. We believe this because justice demands a holy God deal retribution upon sin and Jesus is the only One with the capability to be righteous for the unrighteous. [Romans 3:25, 5:8-9, 1 Peter 2:24, 3:18]

The Resurrection. A true Christian will hold to the resurrection of the crucified body of our Lord, in His ascending into heaven, and His currently priestly intercession on behalf of the church. We believe this as a spiritual necessity because resurrection is the sign of Christ’s sacrificial death and defeat of death itself. We believe this as a historical reality because there has never been anyone or anything with evidence to refute that it took place, or that the followers of Christ had anything to gain via deception. [Mark 16:5-7, Luke 24:6-7]

The Trinity. A true Christian will hold that there is one God who exists in three Persons. God the Father, God the Son, God the Holy Spirit are distinct personalities with distinct roles, while one God. And that One God is the Creator of the universe, omniscient, omnipresent, and immutable. We believe this because of overwhelmingly clear biblical testimony and historic orthodox correspondence via council. [Deuteronomy 6:4, Mark 1:9-11, Acts 17:29, Romans 1:20]

Second Coming. A true Christian will hold to the future, physical, visible, personal, and glorious return of Christ Jesus, which will mean the resurrection of the dead, translation of those alive in Christ, judgment of the just and the unjust, in preparation for the new heavens and new earth. We believe this because of overwhelmingly clear biblical testimony and historic orthodox correspondence via council. [Acts 1:11, 1 Corinthians 4:5, 1 Thessalonians 4:15-5:4]

Next, in the chart above the third circle lists “Important But Not Essential” doctrines (a better name could be “Health of the Church” or “Practice of the Church”) representing doctrines that do not necessarily preclude a Christian from the body of Christ. Consequently, these are important doctrines for the leadership of any local church to know, agree upon, and teach, while members and attendees will inevitably carry a variety of views. For sake of illustration, I’ve listed a sampling of these “third circle” doctrines from my own church below:

Baptism. A leader of our church will hold that baptism is for the believer in Christ who can give sufficient testimony to the basics of Christian beliefs. We baptize by immersion because it is the original meaning of the Greek word for baptism and best symbolizes the reality to which baptism points; our death and resurrection in Christ. We believe that paedobaptism (infant) misses the progressive unfolding of God’s work and word. [Matthew 28:18-20, Acts 2:38, Romans 6:1-11]

Communion. A leader of our church will hold that taking the ordinance (bread and wine) of communion is a symbolic act whereby the believer memorializes Christ’s suffering and death for the believers salvation. We believe this because Christ clearly gave the last supper in symbolic and metaphorical fashion (i.e. “this cup a covenant”) and requested we “do this also in remembrance.” We believe that transubstantiation (the Roman Catholic teaching that Christ’s body becomes the elements themselves) stands against the communicatio idiomatum of the Council of Chalcedon where it was stated that two natures of Christ (deity & humanity) do not intermingle (ex. the attribute of omnipresence cannot communicate with human presence). Therefore Christ’s body, which must be in heaven acting as High Priest and Mediator is not at more than one place at a time, and certainly not in millions of places across the world while believers take communion. [Matthew 26:26-30, 1 Corinthians 11:24-28]

Regeneration. A leader of our church will hold to the soteriological foundation of mankind’s total depravity requiring God’s sovereignty in salvation. This process, often termed the “Doctrines of Grace” simply provide summary of how God moves a sinner from death to life, specifically that 1) mankind is totally dead in sin, 2) requires God elect the sinner unto Himself, 3) demands Jesus sacrificially die on behalf of the chosen sinner, 4) receives God’s effective call to repent and believe 5) and knows the assurance of a salvation he/she cannot lose. We believe this because God must change the heart of a sinner in order for the sinner to receive joy, and for God to receive glory, while anything less limits the capacity of God. [Ephesians 2:1-5, Ephesians 1:4-6, John 6:37-44, Romans 8:29-30]

Premillennialism. A leader of our church will hold to the literal return of Christ to earth for a one thousand-year reign from Jerusalem. We believe this because a literal interpretation of the Bible demands a restoration for Israel, judgment of sin, and one thousand year era of perfect rule by Christ. We believe this because premillennialism (chiliasm) was foundational to the early church including the Patristic Barnabas, Papia, Justin martyr, Irenaeus, Tertullian, Methodius, and Lactantius. We refute the amillennial view (that the kingdom is spiritual) primarily because of its subjective interpretive method. [Revelation 20:1-7, Ezekiel 40-48, Isaiah 11, Luke 1:31-33, Luke 4:16-19]

Classical Cessationism. A leader of our church will hold that the revelatory gift of miracles, healings, and tongues has ceased. We believe that God does supernatural miracles today, including healing, based on His sovereign plan and prayer of His saints, but that these miracles will never accredit or discredit the biblical canon, and are not a gift infused to chosen apostles or members of the church body. We believe this because, 1) The office of apostle was specifically for eyewitnesses of Christ selected by Him, 2) The miracles performed by the apostles were unique to history and far different from any modern counterfeit, 3) The early churches were instructed to pray for the sick and not expect healers, 4) The biblical and classical Greek word for tongues always meant speaking in foreign language, 5) Paul instructs the church of Corinth to discontinue their misuse of these foreign languages. [Ephesians 2:20, 1 Corinthians 15:4-5, James 5:14-15, Acts 2:4-8, 1 Corinthians 14]

My purpose in sharing the circles is to show that when two people meet to discuss theology it is critical to determine which circle of theology is being discussed! Obviously, if a resolute Christian meets with someone who does not hold to the central tenants of historic Christian orthodoxy as well defended by the early church councils (circles #1 and #2 above), they should enter that conversation seeking to save the listener with the Gospel and make that their primary goal. Clearly, this would include Muslims, Hindus, Jehovah Witness, and Mormons, along with a wide variety of liberals, existential pluralists, and even mystics who deny the authority of Scripture (although often they themselves won’t realize their heterodox position until someone points it out).

However, when a resolute Christian engages in theological conversation with another Christian, discussing issues from the third circle outward, much more patience can be extended, focusing special energy on the interpretive nuances of God’s word. This is a huge point because if I’m meeting with a truly born again person I can assume they have a love for God’s word (no matter how immature or misguided) and use the text to win the day. Let’s review seven helpful questions when entering doctrinal dialogue:

What is my relationship to this person? The first question to ask when entering theological dialogue is about your relationship to this person. Is this person a brother or sister in Christ? Obviously, my goal with an unbeliever is salvation, by grace alone, through faith alone, in Christ alone whereas my goal with a fellow believer may simply be Christian unity or correction of some kind. When discussing spiritual matters with an unbeliever it is vital to remember that the “cross” can be found from every doctrine.

Is this a member of my local church? The next item to analyze when entering theological dialogue is whether this person is a member of my church or another local church. If they’ve submitted their spiritual life to the oversight of our pastors then they should sit with a pastor regarding their concerns (Heb 13:17). But, if they attend another local church that meets orthodox Christian criterion we should be very careful about potentially harming their trust and faith in their own pastor. Therefore, when meeting with members of other local bible teaching assemblies be wise in your discussion.

What is my goal? It is always important to remember that the goal of discussing Bible is not pride, winning, or intellectual superiority. The goal is love (1 Tim 1:5) and it should be done patiently (2 Tim 2:24-25). I must enter the discussion with a goal of being patiently gentle and even ready to admit if I am wrong. Love can be presented in the posture, holding it at a coffee house or living room instead of sterile church building. Love can be presented in discussing theology first and then spending thirty minutes catching up on life and praying together. In the end, a person must know that doctrine is important to me because God is important to me and they are important to me.

What doctrine is at stake? It’s important to note if the doctrinal confusion rests around orthodox essentials, church health, or some scholarly enterprise. If the issue is central to the Christian faith I must treat the person as an unbeliever. More so, if the person believes they are saved but in fact are not, I must be prepared to protect others from their false views of theology. If their concern is an outer circle “practice” of the church issue then I can be more patient, enjoy their company, try to learn, and work to challenge them exegetically through the Scriptures.

How do I engage? Always engage any theological discussion exegetically (flowing out of the biblical text). Show them the Scripture in question, explain your interpretation, and provide them scholarly support for your position (which a pastor can help provide). Never use terms “I think” or “I feel” and avoid broad barn-door arguments without technical support. Keep your finger on the text! Social media or email is rarely a profitable place for deep doctrinal discourse as a person cannot see your body language and will feel that you are being sterile or hostile.

What do you owe them? Even when we disagree with someone we owe them a level of understanding (James 1:19). None of us are perfect and we need to enter conversation seeking to understand how they arrived where they did. Are they simply innocent? Immature? Searching? Maybe they grew up in a home that taught errant theology. Maybe no one ever taught them truth. Or, possibly they are divisive. But, you don’t know until you give them the benefit of a listening ear.

How long do you take? When you engage with someone on deep doctrinal issues, the dialogue may take months or even years. If you get hurt, patiently forgive the affront (2 Tim 3:3) and continue forward. If you find that the person is unreceptive to your repeated pleas, pray over a time to exit the situation (Matt 7:6), and if you find the person to be openly divisive reject them after a second warning (Titus 3:10).

[1] Bruce Shelley, Church History in Plain Language, Thomas Nelson, 1982, p. 306