Article: John Gill, the rule of faith and baptist catholicity by David Rathel (original source here)

Article: John Gill, the rule of faith and baptist catholicity by David Rathel (original source here)

BAPTIST CATHOLICITY AND BAPTIST HISTORY

I recently read a Baptist theologian bemoan the fact that every systematic theology he read by a Baptist author featured no serious engagement with the great tradition. This theologian further stated that every lecture he attended while a student at a Baptist seminary was similarly deficient. I cannot speak for his experience, but I suspect he is not the first person to make such claims. Baptists are not exactly known for their catholicity.

One can fortunately find in the history of our movement examples to the contrary. The Orthodox Creed used by the General Baptists commended the Apostles’ Creed as well as the Athanasian Creed, and numerous Baptist doctrinal statements have employed the Trinitarian grammar provided by the Patristic Era. The church covenant still in use at the New Road Baptist Church in Oxford, England, reads, “We denominate ourselves a Protestant Catholic Church of Christ.”

As we explore how some of our Baptist forefathers appropriated the historic tradition, I believe that the works of John Gill, an eighteenth-century Particular Baptist minister, deserve more conversation than they presently receive. His writings display a surprising degree of interest in the larger Christian tradition. His use of the tradition serves as yet another instance of a spirit of catholicity present in the history of the Baptist movement to which contemporary advocates of Baptist catholicity can point. I offer here but one example from Gill’s work—his use of the rule of faith—to demonstrate this fact.

JOHN GILL AND THE RULE OF FAITH

Gill begins his systematic theology with a defense of the need to give an orderly account of theology, acknowledging that what he entitles “systematical divinity” has become unpopular during his lifetime. To offer a justification for such a project, he relies primarily on biblical texts that appear to present Christian convictions in an organized fashion—he highlights in particular Heb. 6:1–2—and references such works as the Apostles’ Creed, Tertullian’s use of the rule of faith, Origen’s On First Principles, and Clement of Alexandria’s Stromata as examples of earlier attempts to present Christian belief in an arranged manner. The tradition, he believes, serves to legitimize the task of systematizing theology by providing numerous historical precedents.

It is Gill’s reference to Tertullian’s use of the rule of faith—the regula fidei or the analogy of faith—that merits closer examination. He makes a significant digression at its mention. Gill explains the rule of faith is not the “sacred writings” though it is “perfectly agreeable to them;” it is “articles and heads of faith, or a summary of gospel truths” that one may collect from Scripture. He believes that texts such as Rom 8:30—one that contains a “rich summary and glorious compendium and chain of gospel truths”—and 1 Tim 1:16 give it legitimacy. In his judgment, they present or at least allude to an organized body of Christian teaching.

Gill believes that Tertullian’s paraphrase of the Apostles’ Creed offers a helpful summary of the content of the rule of faith. While not making the rule of faith and Tertullian’s paraphrase synonymous, he does connect the two closely together when he writes that “such a set of principles these [i.e., the Creed], as, or what are similar to them and accord with the word of God, may be called the analogy of faith.” After quoting the Creed in full as it is presented in Tertullian’s On the Veiling of Virgins, he explains that, though the Creed was not authored by the apostles themselves, it was “agreeable to their doctrine, and therefore called theirs.” It was “received, embraced, and professed very early in the Christian church.”

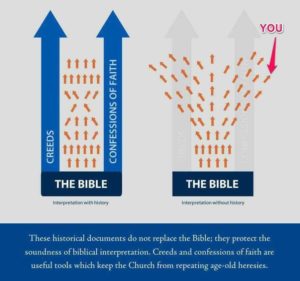

Gill expresses delight in the fact that an orderly account of theology—especially as found in the catholic and historic Apostles’ Creed—provides accountability while doing the work of biblical interpretation. To illustrate this point, he supplies quotations from two German Reformed theologians, Johannes Piscator and David Paræus. Summarizing the former’s remarks on Rom 12:6, a key text on discussions related to the rule of faith, Gill states that the “interpretation of Scripture we bring” must be “analogous to the articles of faith, that is, agreeing with them and consenting to them, and not repugnant.” While Gill does not detail what precise articles of faith Piscator has in mind, a lengthy passage from by Paræus that Gill subsequently cites mentions the Apostles’ Creed and, it appears, the Nicene Symbol. Per Gill, Paræus explained that in Rom 12:6, Paul appears to “prescribe a rule by which all prophesying is to be directed” and that many “understand the rule of Scripture and the axioms of faith such as are comprehended in the symbol of the apostolic faith (or the Apostles’ Creed), which have in them a manifest truth from the Scriptures.” This Paræus quotation further states that “this is the rule of all prophesying (or preaching); therefore, according to the rule of the sacred Scripture and the Apostles’ Creed, all interpretations, disputations, questions and opinions in the church, are to be examined, that they may be conformable thereunto.”

In addition to assisting with interpretation, Gill notes the rule of faith offers further benefits. It can serve as a pedagogical tool—he writes that it “strengthens the faith of others” in gospel truths—and it can assist Christians in expressing their beliefs in an articulate manner. He further explains that it can help Christians display a spirit of unity with one another. It shows agreement in gospel truths “with other Christians in the principal parts of them [i.e., gospel truths].”

This digression on the rule of faith at the beginning of Gill’s systematic theology is rather unusual for a work by an eighteenth-century Baptist minister, and it merits brief analysis. In his work, Gill often uses the terms rule of faith and analogy of faith interchangeably. With these terms, he conveys something akin to what Irenæus and Tertullian meant; that is, he refers to the received tradition of the church catholic. He does not go so far as to speak of obtaining the tradition by way of apostolic succession. He does not, for example, speak of the rule of faith as Irenæus does as “that tradition, which originates from the apostles, [and] which is preserved by means of the successions of presbyters in the churches.” He does, however, freely admit that the rule of faith gains its credibility in part from its universal attestation in the Christian church. As noted, he states that the Apostles’ Creed has weight because it was “received, embraced, and professed very early in the Christian church” and that its usage can display the broader unity of the church catholic because it demonstrates our agreement “with other Christians in the principal parts” of gospel truths.

With these remarks, Gill does not neglect the importance of Scripture or of Scripture’s authority. He often stresses that the rule of faith accords with Scripture’s teaching and is itself a synopsis of the message of the Christian gospel as found in Scripture. His point is that, when interpreting Scripture and constructing one’s theology, one gains assistance from the manner in which the church universal has expressed the teachings of the Scripture, especially in such documents as the creeds. He therefore displays a commitment to his Protestant and Baptist identity as well as an appreciation for the church catholic in his treatment of the rule of faith. The Scripture for him possesses primary authority, but the rich tradition of the church can assist the church and should receive careful consideration.