The following article is by Shawn Wright. (original source here at 9marks ministries) He is an Associate Professor of Church History at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky as well as the Pastor of Leadership Development at Clifton Baptist Church.

The following article is by Shawn Wright. (original source here at 9marks ministries) He is an Associate Professor of Church History at The Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville, Kentucky as well as the Pastor of Leadership Development at Clifton Baptist Church.

Though I am not sure I agree with every point made in the article, there are some interesting points made which can open up worthwhile discussion.

****(AT THE END OF THE ARTICLE IS A RESPONSE BY DR. SAM WALDRON)

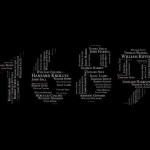

Should you use the 1689 London Confession in your church?

Although the 1689 London Confession (also known as the Second London Confession [SLC] to distinguish it from the 1644, or First London Baptist Confession) is a wonderful statement of Calvinistic Baptist faith, it should not be used as a local church’s statement of faith. Three factors lead to this conclusion

HISTORICAL CONTEXT

First, like all historical documents, the SLC was written in a particular historical context. This context shows the need that Particular Baptists as a whole felt to issue the SLC. The SLC was intended to distance the Baptists from questionable groups and to show their orthodox Protestantism, vis-à-vis other Reformed Protestants. The “Puritan Revolution” in mid-17th century England had its religious expression in the Westminster Assembly. This Puritan group of divines was overwhelmingly Presbyterian in character (though there were a handful of Congregationalists in attendance), so the “standards” it produced —including the Westminster Confession of Faith (WCF; issued in 1646)—were expressions of fundamental Puritan Presbyterianism.

The Puritan revolution failed. With the reign of King Charles II renewed persecution of Protestants began. Before toleration came with the “glorious revolution” of William and Mary in 1688 two other Protestant denominations issued very slightly-modified versions of the WCF. Their reasons for broadly reissuing the WCF were, first, to show their broad agreement with the WCF and, second, to distance themselves from emerging groups like the Quakers who were viewed by orthodox Protestants as holding aberrant doctrine. So the Congregationalists issued the Savoy Declaration in 1658 and the Particular Baptists composed the SLC in 1677. The SLC was issued anonymously in times of Protestant persecution and then with full denominational support after toleration came for Protestants in 1689. We must be aware of the SLC’s place in history, for this influenced its shape.

Of course, the SLC’s historical situation does not mean that the document itself is heretical or even useless for Christians today. That situation does help us, though, to understand the felt need of 17th century Particular Baptists to identify themselves doctrinally with other Protestants in the Reformed tradition. They succeeded from a denomination-perspective. But that does not mean that the SLC should be used as a local church statement of faith.

The SLC’s historical conditioning is also shown in its view of the Roman Catholic bishop of Rome, the pope. Pejorative references to the Catholic church were part and parcel of seventeenth-century Protestant polemic, but a local church would be wiser to restrain from using such violent language in our day. A church can—and should!—disagree with much Catholic theology without having to affirm that “the Pope of Rome” is “that antichrist, that man of sin, and son of perdition, that exalteth himself in the church against Christ, and all that is called God; whom the Lord shall destroy with the brightness of his coming” (26.4).

PURPOSE OF LOCAL CHURCH STATEMENT’S OF FAITH

In the second place, churches must decide on the purpose of a local congregation’s statement of faith. Broadly, a local church’s confession needs to serve two functions. First, it must provide an outline of the church’s theology that will determine the contours of the church’s teaching and preaching ministries. In this way, it can serve as a teaching tool for the church members.

Second, it must also serve as a “hedge” that protects the congregation from false teachers and heresy. The confession therefore needs to be specific enough that it summarizes the doctrinal convictions of the congregation and protects them from error. The SLC certainly meets the second of these criteria, but it fails to meet the first because it is too specific, as we shall now see.

DOCTRINAL SPECIFICITY

The SLC is too doctrinally-specific in some places to serve as a local church’s statement of faith. Churches must decide how tightly to draw their theological boundaries, but I believe the SLC is too tight. The specifics of the following doctrines should not be something that stops believers from uniting with each other as members in a local church. 4.1 seems to require belief in a literal six-day creation. (God created “in the space of six days.”) Chapter 8 teaches that the death of Jesus Christ was specifically for the elect. (For example, 8.5: Christ purchased salvation “for all those whom the Father hath given unto him.”) Definite atonement seems to me to be both biblical and consistent with the other four major soteriological points of Calvinism, but it is also the most debated of the “five points.”

I do not think it is wise for a church to be specific in its statement of faith about a point of doctrine about which there has been much Reformed debate, historically and in the present. Better to have in your congregation those who vigorously adhere to the other four points of Calvinism but question the definiteness of Christ’s atonement than to limit membership to those who have concluded Christ’s death was only for the elect. Chapter 22 teaches a Sabbatarian view of the Lord’s Day, another point on which conservative Christians differ. (See 22.7-8.) Better, however, not to make such a debated point of practice a required belief for church membership (Col. 2:16).

The SLC, then, is a tremendous statement of historic Reformed (and, I think, biblical) doctrine. I recommend it highly as a guide for biblical doctrine. However, it was historically-conditioned in the seventeenth century and it contains too rigid a view of certain doctrines. For these reasons it should not be used as a local congregation’s statement of faith.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Richard P. Belcher and Anthony Mattia. A Discussion of the Seventeenth Century Particular Baptist Confessions of Faith. Southbridge, MA: Crowne Publications, 1990. Helpful discussion showing that the 1644 and 1689 Baptist Confessions of Faith agreed with each other theologically.

A. D. Gillette, ed. Minutes of the Philadelphia Baptist Association, 1707-1807. Springfield, MO: Particular Baptist Press, 2002. Many of the annual circular letters from the years 1774 to 1807 are expositions of various articles of the SLC.

W. Robert Godfrey. “Reformed Thought on the Extent of the Atonement.” Westminster Theological Journal 37 (1975): 133-71. Shows that many Reformed thinkers have questioned the “L” of the five points.

William L. Lumpkin. Baptist Confessions of Faith. Valley Forge, PA: Judson, 1969. Contains historical background and the text of the SLC, as well as of numerous other Baptist confessions.

Samuel E. Waldron. A Modern Exposition of the 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith. Darlington, UK: Evangelical Press, 1989. A section by section exposition of the SLC from the pen of a very capable theologian.

The Proper Holding of the Baptist Confession of 1689

The following is Dr. Sam Waldron’s response, defending the use of the 1689 Confession by local churches.

Introduction

Before I come to the momentous issues that this little essay addresses, there are three things I want to make clear.

A Word about Shawn Wright

I want, first, to say a word about my friend, Shawn Wright. I know and respect Shawn through our mutual associations with Southern Seminary in Louisville. I have cited his work with respect on other occasions. I take no joy in disagreeing with him here. It is only my sense that momentous issues have been raised by his article in the 9 Marks Newsletter that impels me to make this critical assessment of his views.

Hence, I have endeavored not to use his name against him. I will not entitle this article homonymically, “Is Wright Right?” Or even more alliteratively, “Is Wright Wrong?” Or a more assertive alliteration, “Wright Is Wrong!”

A Word about 9 Marks

Let me also make clear my general esteem for the ministry of 9 Marks. I believe that 9 Marks and the Center for Church Reform have been the agent of great good. Nothing I say here is intended to depreciate its ministry. In fact, my fellow elders and I at Heritage Baptist Church of Owensboro, Kentucky wish to recommend to others this ministry. This is one of the reasons why we were so dismayed to find the views expressed by Wright’s article apparently recommended by 9 Marks. I am thankful for the opportunity they provided to respond to those views in a later edition of that newsletter.

A Word about Why I Am Writing

I really have two reasons for writing. First of all, I am deeply desirous to commend the use of the 1689 Baptist Confession as a local church confession. I fear that Wright’s views would have all sorts of negative consequences for the cause of the reformation of Baptist churches in our day.

I am not in expressing such desires and in opposing Wright’s views assuming that the 1689 Baptist Confession is a perfect confession. As the following argument will show, this is not at all my view. I believe that at the right time, and when it can be done with broad unity among Baptists committed to the cause of reformation, the Confession is in need of some slight revision and considerable expansion. I do have doubts as to whether now is the time for such changes, but that is another issue.

My second reason for writing is that Wright has raised an important and practical question in his article. This question is reflected in the title of this response. That question is, “How is the 1689 Baptist Confession to be subscribed by the members of the church?” Must a local church that holds the 1689 Baptist Confession (or, for that matter, any particular confession) require its members to hold or believe every jot and tittle in that confession? This, I think, is a vastly important issue and one about which there is (as Wright’s article illustrates) considerable misunderstanding in our day.

Specific Comments

I have chosen to organize my response to Wright under the two headings of specific comments and general concerns. Wright develops his arguments by means of brief statements about the historical context of the 1689, the purpose of local churches’ statements of faith, and the doctrinal specificity of the 1689, and then a brief conclusion and annotated bibliography. I will make specific comments about each of these matters before coming to my general concerns.

The Historical Context of the 1689

Wright is at pains to inform us that the 1689 is historically conditioned by the religious events taking place in mid-seventeenth century England. His historical account is accurate. He assures us that all historical documents have a particular, historical context. He affirms that the 1689 is neither heretical nor useless as a result. Nevertheless, Wright is seeking through his emphasis on its historical context to support the view that the 1689 should not be “used as a local church statement of faith.” This logic, however, cannot be consistently carried out. All statements of faith are historically conditioned. Are they all, therefore, defective as statements of faith for local churches?

Wright’s comments here leave the impression that the historical origins of the 1689 are somehow “accidental” to the identity of Particular or Reformed Baptists. He implies that the historical circumstances are somehow separable from the identity of Particular and Reformed Baptists. Let us be clear that it is not so. The Particular Baptists were not Baptists who by some historical accident happened to be Reformed. Particular Baptists, as I think Wright knows, emerged from the Puritan movement by means of Puritan Congregationalism.

They were Puritans who by the gradual evolution of Puritan thought in England became Baptists. These Baptists were determined in the First and Second London Baptist Confessions to distance themselves from both Anabaptists and General Baptists. Their origins were distinct. It is completely consistent with this and reflective of their very identity that they should have a Puritan confession. The 1689 Baptist Confession is not an historical accident. Rather, it reflects the distinctive nature of Particular or Reformed Baptists.[1]

Under this point, Wright notes the assertion of the 1689 at 26:4 that the Pope of Rome is the Antichrist. Although this statement reflects the view of prophecy held in common by Protestants of the time, I agree with Wright that this statement ought not to have been made or be part of our confession today.[2] This is one of those places where, in my opinion, a slight revision of the 1689 Confession is necessary. In my experience (having become a Reformed Baptist pastor in 1977 and having shepherded two Reformed Baptist churches during that time) Reformed Baptist churches today, when they express their allegiance to the Confession in their constitutions, commonly make an exception of this statement.[3]

The Purpose of Local Churches’ Statements of Faith

Wright remarks next that a local church’s statement of faith serves two functions. First, it “must provide an outline of the church’s theology that will determine the contours of the church’s teaching and preaching ministries. In this way, it can serve as a teaching tool for the church members.” Second, it “protects the congregation from false teachers and heresy.” Wright maintains that the 1689 works well in the second function but is too specific with regard to the first.

There is a non sequitur in Wright’s reasoning as he moves from these statements about the functions of statements of faith into his next point about doctrinal specificity. Having said that the 1689 fails in the first function noted above—the function of determining the contours of the church’s teaching ministries and as a teaching tool—, he proceeds to argue on this basis that the 1689 is too specific in what it requires for church membership. Has not Wright changed the subject here? Which is it? Is the 1689 as a teaching tool for leading church members to “stand perfect and complete in all the will of God” (Colossians 4:12) or too doctrinally specific as a condition of church membership? Perhaps Wright does not distinguish these two things. They seem, however, emphatically different to me and this difference—as I will make clear below—is foundational to my understanding of confessionalism.

The Doctrinal Specificity of the 1689

Wright finds the 1689 Confession too doctrinally specific and provides three illustrations of this excessive tightness. He finds its assertion of “a literal six-day creation,” “definite atonement,” and “a Sabbatarian view of the Lord’s Day” too strict.[4] He remarks that such doctrinal tightness “stops believers from uniting with each other as members in a local church,” limits “membership” and are “required belief(s) for church membership.”

If he thinks that a church’s holding the 1689 Baptist Confession requires such limitations on membership, Wright is either misinformed or has jumped to an unnecessary conclusion. My own experience among Reformed Baptist churches holding the 1689 contradicts Wright’s assumptions about the practice of churches holding it. I do not favor and have not practiced as a pastor of two different Reformed Baptist churches limiting church membership to those who hold or believe every specific assertion of the Confession. In fact, I have frequently cited in personal conversation both the Christian Sabbath and Definite Atonement as issues where such agreement ought not to be required for church membership.

Further proof that Wright is misinformed has recently been given by the circular letter prepared for the 2005 Association of Reformed Baptist Churches of America General Assembly by Dr. Jim Renihan entitled, “The Doctrinal and Practical Standards for Local Church Membership according to the Bible and the Second London Confession of Faith.” Among many other remarks relevant to the issue at hand, Renihan says:

We must notice what the Confession does not say. It does not say that every believer must have a full-blown understanding of Christian theology, even of its own theology, in order to become part of a church. In fact, the disqualifying condition is not a lack of understanding, but rather the actual commitment to heretical views. So long as the person does not hold such positions, but articulates faith in Christ and lives as an obedient disciple, he or she should be part of the church.[5]

One pastor at the discussion has written this comment about the General Assembly’s discussion of this letter: “Open discussion of the matter revealed a mutual determination among the brethren to continue to implement the SLC with a gracious, redemptive flexibility… For most of our churches, full (not absolute) subscription is required only of the elders.”

Wright and those of his viewpoint may think such flexibility inconsistent. They are, of course, allowed their opinion. They should not, however, misrepresent our practice to themselves or others. Furthermore, I will argue below that such flexibility is perfectly consistent with a church’s holding one of the great Reformed confessions.

Conclusion and Bibliography

Several comments on Wright’s conclusion and bibliography are necessary. First, I want to note Wright’s commendation of the 1689 as “a tremendous statement of historic Reformed (and, I think, biblical) doctrine.” This is good, if a trifle inconsistent. The 1689 Baptist Confession has always functioned and still functions mainly as a local church confession. What else could it be in the midst of a Baptist ecclesiology? If it is no longer to function as such, it is doubtful that few will ever come (like Wright) to “recommend it highly as a guide for biblical doctrine.” Wright’s rejection of it as a local church confession really amounts to a proposal to consign it to the dusty archives of Baptist libraries!

Second, it is interesting to note that Wright thinks Belcher and Mattia’s, A Discussion of the Seventeenth Century Particular Baptist Confessions of Faith a helpful discussion. Actually, Wright’s argument about the historical conditioning of the 1689 is similar to those Belcher and Mattia are opposing in their fine little book.[6]

Third, let me thank Wright for his very kind words about my own A Modern Exposition of the 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith. It should be evident by now, however, that I wrote that book out of the conviction that it could serve as a wonderful “teaching tool for church members” and as such a fine (even the best available) local church confession.

General Concerns

Why Church Membership Does Not Require Full Subscription

Despite my protest that full subscription is not commonly required of church members, Wright may still think that not requiring this is inconsistent. How can the practice of not requiring full subscription of all church members be justified, and why is it important?

The first and most fundamental thing to understand here is that the formally adopted confessions, creeds, or statements of faith of a local church do not possess of themselves divine authority.[7]

They are clearly a species or kind of human authority. Their very designations reveal this. They are confessions—what we confess. They are creeds—from the Latin credo—what the church believes. They are not in themselves divine revelation. Tom Nettles remarks:

That we acknowledge a confession as strictly a humanly composed document is an important step in a quest for unity. All conservative Christian denominations believe that their theologies and ecclesiologies are true reflections of biblical teaching. Hardly any sincere Christian would say, “You are biblical and obviously I am not, but I will stay what I am.” Though they disagree, each believes his position is biblical. The human document meets the essential need of revealing the different understanding of the Bible. When these understandings differ significantly in vital areas, unity of purpose and mission become difficult if not impossible.[8]

One implication of the fact that confessions possess only human authority (and it is an implication not frequently enough appreciated) is that no confession (or church) ought to demand absolute agreement, blind faith, or implicit obedience. Only divine authority may require such responses. Still, this does not mean that confessions have no authority. They have a human kind of authority. The key word used in the Bible for how we should relate to human authority is hupotassein. This verb has for its essential idea subjection or subordination. While subordination may involve agreement and usually requires obedience, these are distinct concepts. Of course, we must also be subject to divine authority, but our duty to divine authority goes far beyond mere subjection. Human authority, however, is commonly and essentially described by way of such subjection. Children are to be subject to parents (Luke 2:51; Hebrews 12:9), slaves to masters (Titus 2:9; 1 Peter 2:18), women to men in church (1 Corinthians 14:34), wives to husbands (Ephesians 5:24; Titus 2:5; 1 Peter 3:1, 5), subjects to their civil authorities (Romans 13:1, 5; Titus 3:1; 1 Peter 2:13), the younger to the elder (1 Peter 5:5), prophets to the whole prophetic band (1 Corinthians 14:32), Christians to Christian ministers (1 Corinthians 16:16). Even demons are subject to the seventy, and this clearly does not mean that they agree with them (Luke 10:17).

It is not merely generic human authority that confronts us in the church’s confession. In the local church and in its confessions we have to do with a special kind of human authority. Christians unlike children, slaves, and subjects may choose the local church they will join. Though every Christian must seek to join a local church, he is not obligated to join any particular local church. Here he is left to his own conscience bound by the Word of God. Clearly, where subordination to a human authority is voluntary in its origin (whether of a prospective wife to a prospective husband or of a prospective church member to a prospective church and its confession) as much agreement as possible should be sought. This will make the relationship sweeter and better for all concerned. Yet, just as a bride ought not to think that she must agree with her prospective husband about everything in order to submit to him, so also a prospective church member ought not to think that absolute agreement with his church, its elders, or its confession is necessary in order to subordinate himself to them. To think that such agreement is required in order to such submission would practically destroy both marriage and the local church. None of us—not even any of us Christians—has such perfect agreement with other human beings.

All this means several very practical things with regard to the church member’s relationship to the church and its confession. Of course, the elders on behalf of the church must inquire if a prospective church member has any actual disagreements with the confession. The elders must determine that any such disagreements are not foundational errors, are consistent with a credible profession of faith, and consistent with church membership on other grounds. Yet, from the viewpoint of the prospective member only the agreement sufficient to make subordination possible is necessary. This requires all prospective members to read carefully the church’s confession. The church member need not, however, fully understand the confession of the church or fully agree with it. If he agrees with it sufficiently that he can submit to it sweetly, live with it peaceably, and respond to its exposition teachably, this is all that it is required. Of course, if someone cannot be sweet, peaceable, and teachable under the teaching of any given confession, he should not join a church that holds it.

It is clear from all this that a vital distinction must be maintained between the members and the elders of the church. Members need only submit to the confession. Elders are obliged to teach it (1 Timothy 3:2; 2 Timothy 2:24; Titus 1:9). This clearly implies that elders sustain a different kind of relation to the church’s confession. Specifically, it implies a much greater degree of agreement than that required of church members. From this perspective, Wright’s slipping (in the non sequitur I pointed out above) from the use of the confession as a teaching tool to the requirement of full subscription of church members obscures a vital distinction with regard to confessionalism.

Failure to make this vital distinction has serious consequences. In the first place, Wright’s position seems to require that the church confess only as much its newest, baptized member understands and believes. Is the church’s confession to be limited to what its newest baptized member believes? I think not. The church is required to believe and confess much more than this. The great Reformation confessions act on this principle and are repositories and treasuries of what the church had come to believe over the previous 1600 years. The confession of the church must not be held hostage to the beliefs of its youngest members. The youngest members must be nurtured redemptively and lovingly up into the fullness of its faith. If the newest and youngest members already believe and understand a church’s statement of faith, what becomes of the function of the confession as a teaching tool?

In the second place, it may be suggested that Wright’s neglect of this vital distinction between members and ministers results in making it divisive to insist on the importance of any doctrine beyond that contained in a church’s simple statement of faith. If the church’s unity is expressed in its statement of faith, and its statement of faith is limited to what its youngest members believe, then does it not become divisive to insist on the importance of definite atonement or anything else that the most immature member does not understand? Such teaching of the deeper things of God, then, must never be made central to the life of the church because it would threaten the unity of the church which is based on a simpler faith. On this view it would become divisive for a church to bear public, formal, and explicit witness even to the doctrines of grace. I do not think Wright or those who share his view want this consequence, but I think they need to explain why their view does not lead to it.

Why Differences Should Not Be Veiled by Complaints about Specificity

Wright’s desire for less specificity in confessions veils what I believe to be important doctrinal differences between him and the 1689 Confession. Let me hasten to say that he does not seem to be deliberately hiding such differences. Let me also hasten to say that he may not think these differences important. But I may think them important! I should be allowed to decide for myself if they are—without being accused of exclusivity, rigidity, and tightness. Isn’t this the very kind of “moderate” argument that Wright rejects? Isn’t he saying, “Can’t we all just get along? Why do we need so much doctrinal specificity?” Now, of course, we must all draw the line somewhere. I have even said that in this little essay. I am not prepared to assume that no great doctrinal differences are revealed by variant views on six-day creationism, definite atonement, or the Christian Sabbath. Charges of too much doctrinal specificity in the 1689 Confession tend to derail important theological and practical discussions that need to take place today among Baptists of Calvinistic persuasion.

Why Churches Ought to Hold the 1689 Baptist Confession of Faith

This meaty and profoundly reverent confession of faith holds several benefits for subscribing churches. Churches should hold the 1689 because:

It is a repository of the great doctrines of Christian orthodoxy regarding the Scriptures, the Trinity, and the Person of Christ.

Its distinctives are biblical. Its Reformed approach to God, His decree, the work of Christ, the application of salvation, the law of God, and Christian worship is biblical. Its Baptist approach to the covenants, the ordinances, and the local church are all deeply and substantially biblical.

It identifies them with their historical origins. There are great and important historical differences between Anabaptists, General Baptists, and Particular Baptists.

It provides both an adequate standard of church membership and a wonderful goal for instruction. The 1689 provides a rich treasure of truth to set before new members as a goal for their Christian maturation.

Let me close with an illustration. Wright invites you to go with him to the church picnic and share with him his little basket of truth. The food in it is good and nutritious but limited in its variety, flavor, and quantity. You eat of every dish, but find that it leaves you with cravings. I also invite you to go with me to the church picnic. I have in the back of my SUV a large cooler full of wonderful ice-cold drinks and a gigantic picnic basket filled with luscious foods. You may think at first that though the spread looks inviting overall, it seems too rich and exotic for the appetite of one person. You will find, however, that each morsel serves as an appetizer for the next. And the more you linger over each dish the more delightful the whole seems to be. I will not even make you eat every one of my treats—even though I think them all delicious—but I am sure that eventually you will find all of them satisfying and salubrious. It seems to me the reader’s choice is clear.

[1]Erroll Hulse, An Introduction to the Baptists (Haywards Heath, Sussex, England: Carey Publications, 1973), 1720; James M. Renihan, The Practical Ecclesiology of the English Particular Baptists (PhD dissertation, Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, 1997), 1–31.

[2]The meaning of the Confession’s assertion must be understood in the context of the historicist interpretation of prophecy. It is “the line of popes” that is “the antichrist.” While I do not think that this is the reference of 2 Thessalonians 2 and 1 John 2, it remains true that (in spite of the positive Roman Catholic stand on moral and family issues today) Tridentine Catholicism is “anti-Christian.” It also remains possible that a future pope might be “the antichrist.”

[3]The constitution of both the Reformed Baptist churches of which I have been a pastor makes this exception: “We regard the London Baptist Confession of Faith of 1689 (excepting the assertions regarding the salvation of the mentally incompetent [10:3] and the identity of the antichrist [26:4]) . . . as excellent, though not inspired, expressions of the teaching of the Word of God. Because we acknowledge the Word of God written to be the supreme authority in all matters of faith, morals, and order, we adopt these two historic documents as our doctrinal standards. We find them to be an assistance in controversy, a confirmation in faith, and a means of edification in righteousness.”

[4]Wright reveals his own anti-sabbatarian tendency by citing Colossians 2:16 in support of not making the Christian Sabbath a required belief. If Colossians 2:16 has any reference to “the Christian Sabbath,” Wright is not only correct that such a view should not be a requirement for church membership, but also shows that any sabbatic view of the Lord’s Day is wrong and tends to the Colossian heresy. Of course, the problem is that no knowledgeable proponent of the Christian Sabbath thinks that Colossians 2:16 has any reference to Lord’s Day observance.

[5]James M. Renihan, “The Doctrinal and Practical Standards for Local Church Membership according to the Bible and the Second London Confession of Faith,” Circular Letter prepared for the 2005 ARBCA General Assembly.

[6]Richard P. Belcher and Anthony Mattia, A Discussion of the Seventeenth Century Particular Baptist Confessions of Faith (Southbridge, MA: Crowne Publications, 1990), i–vi.

[7]Of course, I acknowledge that they are intended to articulate the teachings of divine revelation. In this restricted sense they possess a derivative divine authority, but they do not possess this authority of themselves.

[8]Tom Nettles, “The Role of Confessions in Baptist Faith,” Founders Journal 4 (Spring 1991).