Justin Taylor has put together an article entitled “Exceptions for Abortion?” which contains much wisdom about this very sensitive subject. He writes:

Justin Taylor has put together an article entitled “Exceptions for Abortion?” which contains much wisdom about this very sensitive subject. He writes:

I assume by now that most readers are aware of the controversy regarding comments by candidate Richard Mourdock, who is running for Senate, when asked about the issue, he responded:

This is that issue that every candidate for federal, or even state, office faces, and I too stand for life. I know there are some who disagree and I respect their point of view and I believe that life begins at conception. The only exception I have [for abortion] is in that case [where] the life of the mother [is threatened]. I struggled with it for a long time, but I came to realize that life is a gift from God. And I think even when life begins in that horrible situation of rape that it is something that God intended to happen.

President Obama, through a spokesperson, “felt those comments were outrageous and demeaning to women.”

There are many angles to this story, including media ignorance, media malfeasance, political clumsiness, bioethics, and Christian witness.

Many members of the media pounced on the story, reporting that Mr. Murdock said that rapes were intended by God. Al Mohler has an important commentary on this today. He writes:

The controversy over his statements reveals the irresponsibility of so many in the media and the political arena. The characterizations and willful distortions of Mourdock’s words amount to nothing less than lies.

A couple of liberal writers have recognized the same. See, for example, Kevin Drum’s “Richard Mourdock Gets in Trouble for His Extremely Conventional Religious Beliefs” and Amy Sullivan’s “Why Liberals Are Misreading Mourdock.”

But most seemed to be twisting the candidate’s words and also baffled by the worldview. Get Religion‘s Mollie Hemingway offered some advice to fellow journalists:

If you do these two things — bone up on just the very lowest level basics of Christian teaching on theodicy and meet a pro-lifer and find out what they really think — you might not lead your newscasts with a mangling of the news that some pro-lifers really believe (gasp!) that the circumstances of your conception and birth do not determine your worth and that every single child in the world is created and loved by God. You might learn about this newfangled ancient teaching that God causes good to result from evil.

But Mohler does not think the media, while certainly culpable, is entirely to blame:

At the same time, Mr. Mourdock is responsible for giving the media and his political enemies the very ammunition for their distortions. . . . The debate question did not force Mourdock to garble his argument. The cause of defending the unborn is harmed when the argument for that defense is expressed badly and recklessly, and Mourdock’s answer was both reckless and catastrophically incomplete.

Mohler is right: we must speak with precision, clarity, and compassion on this issue. We must put the question in perspective:

Any reference to rape must start with a clear affirmation of the horrifying evil of rape and an equal affirmation of concern for any woman or girl victimized by a rapist. At this point, the defender of the unborn should point to the fact that every single human life is sacred at every point of its development and without regard to the context of that life’s conception. No one would deny that this is true of a six-year-old child conceived in the horror of a rape. Those who defend the unborn know that it was equally true when that child was in the womb.

Mohler also looks at the broader issue of exceptions:

One truth must be transparently clear — a consistent defense of all human life means that there is no acceptable exception that would allow an intentional abortion. If every life is sacred, there is no exception.

The three exceptions most often proposed call for abortion to be allowed only in cases of rape, incest, or to save the life of the mother. These are the exceptions currently affirmed by Mitt Romney in his presidential campaign. What should we think of these?

Mohler gives his answer:

First, when speaking of saving the life of the mother, we should be clear that the abortion of her unborn child cannot be the intentional result. There can be no active intention to kill the baby. This does not mean that a mother might, in very rare and always tragic circumstances, require a medical procedure or treatment to save her life that would, as a secondary effect, terminate the life of her unborn child. This is clearly established in moral theory, and we must be thankful that such cases are very rare.

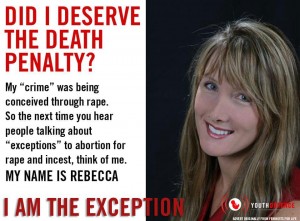

Next, when speaking of cases involving rape and incest, we must affirm the sinful tragedy of such acts and sympathize without reservation with the victims. We must then make the argument that the unborn child that has resulted from such a heinous act should not be added to the list of victims. That child possesses no less dignity than a child conceived in any other context.

What does this look like practically, in everyday conversations?

Scott Klusendorf points out that there are two types of people who ask about rape and abortion: the learner and the crusader. It’s helpful to know who you are dealing with. ” The learner is genuinely trying to work through the issue and resolve it rationally. The crusader just wants to make you, the pro-lifer, look bad.” In both cases, Klusendorf points out, “it’s our job to demonstrate wisdom and sensitivity.”

So when someone says that a child conceived by rape will remind the woman of this heinous crime forever, Klusendorf responds:

That’s an important question and you are absolutely right: She may indeed suffer painful memories when she looks at the child and it’s foolish to think she never will. I don’t understand people who say that if she’ll just give birth, everything will be okay. That’s easy for them to say. They should try looking at it from her perspective before saying that. Even if her attacker is punished to the fullest extent of the law—which he should be—her road to recovery will be tough.

He then delicately and gently asks one primary follow-up question:

Given we both agree the child may provoke unpleasant memories, how do you think a civil society should treat innocent human beings that remind us of a painful event? . . . Is it okay to kill them so we can feel better?

In the course of the conversation, he is trying to get them to see the following:

If the unborn are human, killing them so others can feel better is wrong. Hardship doesn’t justify homicide.

Admittedly, I don’t like the way my answer feels because I know the mother may suffer consequences for doing the right thing. But sometimes the right thing to do isn’t the easy thing to do.

Here are two thought experiments that might help:

Suppose I have a two-year-old up here with me. His father is a rapist and his mother is on anti-depressant drugs. At least once a day, the sight of the child sends her back into depression. Would it be okay to kill the toddler if doing so makes the mother feel better?

And:

Suppose I’m an American commander in Iraq and terrorists capture my unit. My captors inform me that in 10 minutes, they’ll begin torturing me and my men to get intelligence information out of us. However, they are willing to make me an offer. If I will help them torture and interrogate my own men, they won’t torture and interrogate me. I’ll get by with no pain. Can I take that deal? There’s no way. I’ll suffer evil rather than inflict it.

Again, I don’t like how the answer feels, but it’s the right one. Thankfully, the woman who is raped does not need to suffer alone. Pro-life crisis pregnancy centers are standing by to help get her through this. We should help, too.

Back to how politicians should answer this. Here is Doug Wilson’s suggestion to pro-life candidates:

When a rape results in a pregnancy, this means that we are now dealing with three people instead of two. Two of those three are innocent, and one of them is guilty. Take a case of violent rape. The pro-choice ghouls want to do two things—first, they want to go easy on the guilty one, refusing to execute him, while executing one of the innocent parties for something his father did, and secondly, they want to make out anyone who objects to this arrangement as the callused one.

In the future (as if any of these guys are taking my counsel), pro-life candidates for office need to answer the question in this way: “That is an excellent question, but we have to settle certain things first before we answer it. When a rape results in a pregnancy, are we dealing with three people or two?” And then he should refuse to answer the question until the reporter tells him “three or two,” along with the reasons why. This is how the Lord handled this sort of question.

See also Trevin Wax’s post on what pro-life politicians should say about abortion and rape (as well as his post on the 10 questions you never hear a pro-abortion-rights candidate asked).

But the foregoing doesn’t answer the question about legislation and how to think about these issues in light of our current cultural and political context. It’s here where Mohler’s perspective could get more controversial, especially for those who do not recognize the role of prudence in cultural change and the reality of governance:

We must contend for the full dignity and humanity of every single human life at every point of development and life from conception until natural death, and we cannot rest from this cause so long as the threat to the dignity and sanctity of any life remains.

In the meantime, we are informed by the fact that, as the Gallup organization affirmed just months ago, the vast majority of Americans are willing to support increased restrictions on abortion so long as those exceptions are allowed. We should gladly accept and eagerly support such laws and the candidates who support them, knowing that such a law would save the life of over a million unborn children in the nation each year.

Can we be satisfied with such a law? Of course not, and we cannot be disingenuous in our public statements. But we can eagerly support a law that would save the vast majority of unborn children now threatened by abortion, even as we seek to convince our fellow Americans that this is not enough.

We must argue for the dignity, humanity, and right to life of every unborn child, regardless of the context of its conception, but we must argue well and make our arguments carefully. The use and deliberate abuse of Richard Mourdock’s comments should underline the risk of falling short in that task.