In my teaching and preaching ministry, I primarily use the English Standard Version (ESV) and it is the Bible most frequently used in our services at King’s Church here in Phoenix.

In my teaching and preaching ministry, I primarily use the English Standard Version (ESV) and it is the Bible most frequently used in our services at King’s Church here in Phoenix.

I say this for two main reasons; the first being that it can be very confusing if we have the different words in front of us as the sermon is being preached. This can be very alarming for new Christians who are not aware of the issues and see a text in front of them that is so different from what the preacher is using.

Decades ago, there was only one real Bible version of choice, the King James Version. Though it was the Geneva Bible with its Reformation based explanatory study notes that first came over to the shores of America on the Mayflower, the growing popularity of the KJV eventually made seeing the Geneva Bible a rare event in church services and in the homes of Christians in the USA.

The King James Version is certainly an excellent translation which has served the church for many generations. However, the meaning of words have changed a great deal in the centuries since the first printing of the KJV in 1611. Many preachers (me included) found that when using it, much time was required in a sermon to update and explain the archaic language used. A newer translation removes the need for this.

In addition to the archaic language of the KJV, what we know of the original text and languages has improved significantly in the last 400 years or so. The Church in our day has needed a Bible translation which reflects this great advancement in scholarship.

In some church services, there can be as many as 15-20 different versions in use in the congregation. Of course, people can use any translation they like. They are free to do so! Yet I think it is very helpful for pastors and elders to recommend one main translation for the congregation as this eliminates any potential confusion.

With this as a foundation, the next question we need to ask is “which is the best Bible to use?”

This leads me to talk about the second reason for choosing the ESV. It stems from the desire to have an essentially literal translation (a “word for word” translation) in use rather than a dynamic equivalent, or “thought for thought” one. As the article below states, the primary advantage in choosing a “word for word” translation is that “preachers, teachers, and church people will have the confidence that their Bible gives them the equivalent English words for what the authors of the Bible actually wrote. They do not need to wonder at every point where translation ends and commentary begins. They do not need to worry that important material has been omitted from the original.”

Certainly, there are other good ESL translations out there. For years I have used the NASB (New American Standard Bible) which is tremendously accurate as a translation. However, if reason number one above was ever to be achieved, a choice needed to be made. The ESV is known for both its very accurate translation and for its language flow. It is very easy to read and to memorize. It is great for both adults and children.

I write these words here and present this short article with questions and answers below (by Leland Ryken) because I wanted you to know some of the thinking behind the ESV being our Bible of choice here at King’s Church.

I write these words here and present this short article with questions and answers below (by Leland Ryken) because I wanted you to know some of the thinking behind the ESV being our Bible of choice here at King’s Church.

While we are still on the subject of Bibles, I am often asked to recommend a good Study Bible. I always point people to either the Reformation Study Bible or the ESV Study Bible, both of which use this same English Standard Version (ESV) text. These are the two exceptional Study Bibles out there. I love using both of them and am confident that in directing people to these notes, they will not be led astray. I certainly cannot say that about all Study Bibles out there but these two are remarkable gifts to the Body of Christ at large. You will usually see me preaching using one of these Study Bibles.

– Pastor John Samson

On Bible Translation: A Q & A with Leland Ryken

From the KJV to the NIV, NLT, ESV, and beyond, English Bible translations have never been as plentiful as they are today. This proliferation has also brought some confusion regarding translation differences and reliability. Leland Ryken agreed to join us for a two-part Q&A on Bible Translation. In his new book, Understanding English Bible Translation, he clarifies some of the issues of modern Bible translation and makes a case for an essentially literal approach. Join us as he answers a handful of timely questions:

When did you first become interested in issues of translation philosophy?

My interest has been marked by two key moments along the way. The first came at the time of the release of the NIV, when I was asked to write a literary review of the new translation for Christianity Today. That assignment just happened to coincide with the appearance of a book of essays that criticized modern translations (chiefly the RSV and New English Bible) as being inferior to the KJV. Although I was only vaguely aware of how translation philosophy entered that debate, I became semi-expert in the deficiencies of modern translations.

My interest has been marked by two key moments along the way. The first came at the time of the release of the NIV, when I was asked to write a literary review of the new translation for Christianity Today. That assignment just happened to coincide with the appearance of a book of essays that criticized modern translations (chiefly the RSV and New English Bible) as being inferior to the KJV. Although I was only vaguely aware of how translation philosophy entered that debate, I became semi-expert in the deficiencies of modern translations.

After serving as a member of the translation committee that produced the ESV, I asked Lane Dennis if he wanted me to expand my review of the NIV into a book-length exploration of the issues surrounding the rival translation philosophies. Lane surprised me by saying yes, so that was followed by my immersion in the subject of the opposed philosophies known as dynamic equivalence and essentially literal translation. The learning curve was steep, but very rewarding.

I can imagine that some experts in the Bible in its original languages find it frustrating that an amateur like me has authored books on Bible translation. However, I was struck by the verdict of a New Testament scholar who had initially been skeptical of my authoring a book on Bible translation, but who said after reading my book that only an outsider to the guild could have written such a book.

What are the two main translation philosophies, and how do they differ?

Although the label essentially literal is a recent coinage, until the middle of the twentieth century the goal of English Bible translation was to find the English words that most closely correspond to the meaning of the words of the biblical text in its original languages. The goal was to find the verbal equivalent of the original text.

Adherents of “dynamic equivalence” (and the more recent label “functional equivalence”) do not necessarily feel obliged to translate the actual words of the original. Instead, these translators often engage in commentary on the biblical text instead of translation of it. This is done by bypassing the words of the original and offering an interpretation of its “content meaning” as distinct from its “lexical meaning.”

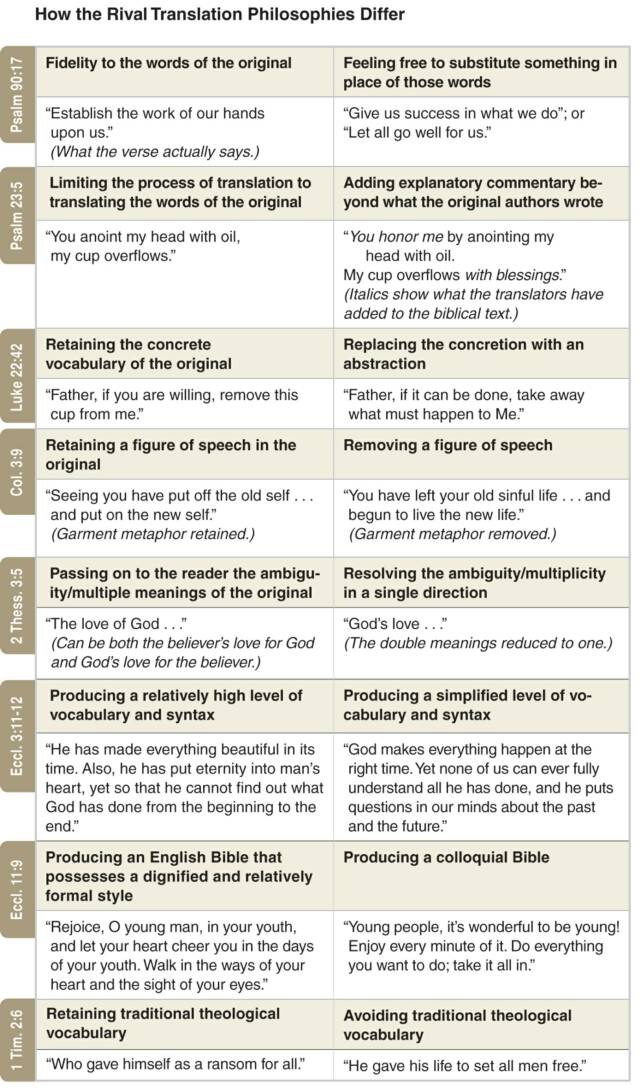

In my new book, Understanding English Bible Translation, I stress that the terminology of dynamic equivalence is misleading in covering the range of practices followed by translators. “Essentially literal” translation teams adhere to the following practices in addition to seeking to reproduce in English the actual words of the original: (1) they produce a dignified text that belongs to standard formal English; (2) they preserve the literary effects of the original, including metaphors and figures of speech; (3) they retain multiple or ambiguous references contained in the original text; (4) they create a rhythmically smooth flow of language; (5) they preserve the qualities of the biblical text that are rooted in the ancient world that produced only the Bible.

Only a relatively small quantity of what we find in a dynamic equivalent translation consists of finding an equivalent in modern life for a detail in the ancient biblical text. The following list of methods employed by dynamic equivalent translators gives a more accurate picture of what these translators do: (1) they produce a colloquial Bible that sounds like the informal oral speech of the dormitory and bus stop (but not the written speech of the newspaper and Newsweek); (2) they do not place a priority on preserving the literary qualities of the Bible; (3) they often remove figurative language from sight and replace it with an interpretation of it; (4) they often remove ambiguous references from the biblical text by making a preemptive choice of one meaning from the list of possible meanings; (5) they make the Bible seem like a modern book rather than an ancient book.

The chart below exemplifies the differences in translation philosophy (adapted from pg 33).

Why do you object to the cliché that “all translation is interpretation?”

I object because it is a misleading statement and it should be challenged every time it is put on the table in the public forum. There are different types or levels of interpretation, and this gets lost in the statement that all translation is interpretation.

All translation is lexical interpretation, and that is all that can be accurately said about “all” translation. All translation is the translator’s interpretation of what English word or phrase best captures the meaning of the equivalent word in the original text.

The other kind of interpretation is what we call exegesis and commentary. It offers an interpretation of the meaning of a text—not usually an individual word, as in lexical interpretation, but meaning of the broader content of an utterance. For example, to render Psalm 23:5a as “you anoint my head with oil” is a lexical decision as to what English words are the verbal equivalent of the words of the original. But when a dynamic equivalent translation renders that verse as “you welcome me as an honored guest,” we have moved beyond lexical interpretation to commentary.

The reason dynamic equivalent translators love the formula “all translation is interpretation” is that it makes their practice seem normal. The implication is that dynamic equivalence is no different from the procedure of essentially literal translators. In fact the difference between the two translation philosophies is not a difference of degree but of kind.

Why is it important to preserve a metaphor instead of interpreting what it means?

Even with a “secular text,” it is objectionable to disregard authorial intention. Authors have a right to have their utterances respected as representing what they intended to say. But with the Bible a whole additional level of objection enters. As biblical scholar Raymond Van Leeuwen correctly states, to eliminate biblical metaphors from sight is to thwart the work of the Holy Spirit, who gave us the metaphors in the first place.

There is also a literary principle at work. It is a rare image or metaphor that embodies only one meaning. When dynamic equivalent translators reduce the range of meanings to one, they short-circuit the process of communication. What dynamic equivalent translators think of as helping a reader is really a process of robbing a reader.

Isn’t the goal of conveying the meaning of the biblical text commendable?

One of the clichés of the dynamic equivalent movement is “meaning based translation,” rather than “word-based translation.” But the dichotomy is a false one. Essentially literal translators believe that the meaning that the biblical authors intended us to grasp is embodied in the words that they used. The implication of “meaning-based” advocates is that essentially literal translations lack meaning!

What should we make of the fact that the New Testament was written in Koiné Greek—the everyday language of common people rather than the Greek of the philosophers and tragedians?

Strictly speaking, all that Koiné identifies is the language used by most New Testament writers. That still leaves open the stylistic level of what the authors wrote in that language. To cite a parallel, Shakespeare and Milton decided to write their literary works in native English rather than the Latin that was the international language of intellectual discourse in their day. The stylistic range of what they wrote in English runs the gamut, though it is predominantly toward the “high” end of the continuum. By itself, the fact that New Testament writers wrote in Koiné is a great deal less important than advocates of colloquial English Bibles have led us to believe.

What are the advantages of a church choosing an essentially literal translation?

The primary advantage is that preachers, teachers, and church people will have the confidence that their Bible gives them the equivalent English words for what the authors of the Bible actually wrote. They do not need to wonder at every point where translation ends and commentary begins. They do not need to worry that important material has been omitted from the original.

Additionally, we need to remember that the rival translation philosophies entail more than the question of literal vs. free. Church people who choose the ESV and the NKJV will also enjoy the advantages of a literarily powerful and beautiful Bible, a Bible with exaltation and dignity, a Bible that reads smoothly in oral utterance of it, and a translation that does not narrow down the legitimate range of meanings to what a translation committee decided to put before the reader.

For more information, check out Ryken’s new release, Understanding English Bible Translation: A Case for an Essentially Literal Approach.

Having now talked about translation, here is an article where I discuss the Study Bible I most recommend.

Pastor Kevin DeYoung: “We are blessed with many fine English translations. But I have been a reader of the ESV since it first came out and I am very happy our church made the switch. Several years ago our church switched to the ESV. To help with this transition I wrote a lengthy paper for the congregation. Last year Crossway asked if they could turn that paper into a short booklet. You can read more about the pamphlet on the Crossway blog and also download it for free. You can also access the PDF here.”