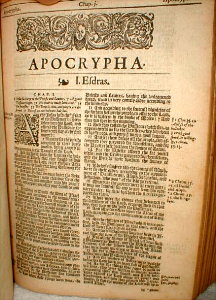

You may have wondered why the Roman Catholic Church includes books in their “canon” that are not in our Protestant Bibles. They include books written in the Intertestamental Period (the 400 years between Malachi and Matthew in our Bibles). These are known as The Apocrypha.

You may have wondered why the Roman Catholic Church includes books in their “canon” that are not in our Protestant Bibles. They include books written in the Intertestamental Period (the 400 years between Malachi and Matthew in our Bibles). These are known as The Apocrypha.

Protestants have not included the books of the Apocrypha in the canon. These are regarded as Deuterocanonical books or books on a secondary (deutero) level to Scripture.

It was not until 1546 at the Council of Trent that the Roman Catholic Church officially declared the Apocrypha to be part of the canon (with the exception of 1 and 2 Esdras and the Prayer of Manasseh). It is significant that the Council of Trent was the response of the Roman Catholic Church to Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation because the books of the Apocrypha contain support for Catholic doctrines such as prayers for the dead and justification by faith plus works.

The following is an excerpt from an article by Dr. Greg Bahnsen entitled, “The Concept and Importance of Canonicity.”

In terms of the previous discussion, then, what should we make of the Roman Catholic decision in 1546 (the Council of Trent) to accept as canonical the apocryphal books of “Tobit,” “Judith,” “Wisdom,” “Ecclesiasticus,” “Baruch,” “I and II Maccabees”?

Such books do not claim for themselves ultimate divine authority. Consider the boldness of Paul’s writing (“if anyone thinks he is spiritual, let him acknowledge that what I write is the commandment of the Lord” — I Cor. 14:37-38; if anyone “preaches any other gospel that what we preached to you, let him be accursed” – Gal. 1:8). Then contrast the insecure tone of the author of II Maccabees: “if it is poorly done and mediocre, that was the best I could do” (15:38). Moreover, when the author relates that Judas confidently encouraged his troops, that boldness came “from the law and the prophets” (15:9), as though this were already a recognized and authoritative body of literature to him and his readers. (This is also reflected in the prologue to Ecclesiasticus.) I Maccabees 9:27 recognizes the time in the past when “prophets ceased to appear among” the Jews.

The ancient Jews, to whom were entrusted the “oracles of God” (Rom. 3:2), never accepted these apocryphal books as part of the inspired canon — and still do not to this day.[4]

Josephus speaks of the number of Jewish books which are divinely trustworthy, not leaving a place for the apocryphal books. Josephus expressed the common Jewish perspective when he said that the prophets wrote from the time of Moses to that of Artaxerxes, and that no writing since that time had the same authority. The Jewish Talmud teaches that the Holy Spirit departed from Israel after the time of Malachi. Now, Artaxerxes and Malachi both lived about four centuries before Christ, while the books of the Apocrypha were composed in the vicinity of two centuries before Christ.

When Christ came, neither He nor the apostles ever quoted from the apocryphal books as though they carried authority. Throughout the history of the early church, the acceptance of the Apocrypha was no better than spotty, inconsistent, and of ambiguous import — the bottom line being that the books never gained universal respect and clear recognition as bearing the same weight and authority as the very Word of God.

The first early Christian writer to address explicitly the question of an accurate list of the books of the Old Covenant was Melito (bishop of Sardis, about 170 A.D.), and he does not countenance any of the apocryphal books. Athanasius forthrightly rejected Tobit, Judith, and Wisdom, saying of them: “for the sake of greater accuracy… there are other books outside these [just listed] which are not indeed included in the canon” (39th festal letter, 367 A.D.).[5]

The scholar Jerome was the main translator of the Latin Vulgate (which Roman Catholicism later decreed has ultimate authority for determining doctrine). About 395 A.D., Jerome enumerated the books of the Hebrew Bible, saying “whatever falls outside these must be set apart among the Apocrypha.” He then lists books now accepted by the Roman Catholic church and categorically says they “are not in the canon.” He later wrote that such books are read “for edification of the people but not for establishing the authority of ecclesiastical dogmas.” Likewise, many years later (about 1140 A.D.), Hugo of St. Victor lists the “books of holy writ,” adding “There are also in the Old Testament certain other books which are indeed read [in church] but are not inscribed…in the canon of authority”; here he lists books of the apocrypha.

The apocryphal books were sometimes highly regarded or cited for their antiquity or for their historical, moral, or literary value,[6] but the conceptual distance between “valuable” and “divinely inspired” is considerable.

Thus the 1395 Wycliffe version of the Bible in English included the Apocrypha and commends the book of Tobit in particular, yet also acknowledges that Tobit “is not of belief” — that is, not in the same class as inspired books which can be used for confirming Christian doctrine. Likewise, the Thirty-Nine Articles of the Church of England (1562) names the canonical books of Scripture in one separate class, and then introduces a list of apocryphal books by saying: “And the other books the Church doth read for example of life… by yet doth it not apply them to establish any doctrine.”[7] This is likewise the attitude of most Roman Catholic scholars today, who regard the books of the Apocrypha as only “deutercanonical” (of secondary authority).[8]

The Protestant churches have never received these writings as canonical, even though they have sometimes been reprinted for historical value. Even some Roman Catholic scholars during the Reformation period disputed the canonical status of the apocryphal books, which were accepted (at this late date) it would seem because of their usefulness in opposing Luther and the reformers — that is, for contemporary and political purposes, rather than the theological and historical ones in our earlier discussion.

Finally, the books of the Apocrypha abound in doctrinal, ethical, and historical errors. For instance, Tobit claims to have been alive when Jeroboam revolted (931 B.C.) and when Assyria conquered Israel (722 B.C.), despite the fact that his lifespan was only a total of 158 years (Tobit 1:3-5; 14:11)! Judith mistakenly identifies Nebuchadnezzar as king of the Assyrians (1:1, 7). Tobit endorses the superstitious use of fish liver to ward off demons (6: 6,7)!

The theological errors are equally significant. Wisdom of Solomon teaches the creation of the world from pre-existent matter (7:17). II Maccabees teaches prayers for the dead (12:45-46), and Tobit teaches salvation by the good work of almsgiving (12:9) — quite contrary to inspired Scripture (such as John 1:3; II Samuel 12:19; Hebrews 9:27; Romans 4:5; Galatians 3:11).

The conclusion to which we come is that the books of the Roman Catholic Apocrypha fail to demonstrate the characteristic marks of inspiration and authority. They are not self-attesting, but rather contradict God’s Word elsewhere. They were not recognized by God’s people from the outset as inspired and have never gained acceptance of the church universal as communicating the full authority of God’s own Word. We must concur with the Westminster Confession, when it says: “The books commonly called Apocrypha, not being of divine inspiration, are no part of the canon of scripture; and therefore are of no authority in the Church of God, nor to be any otherwise approved, or made use of, than other human writings” (I, 3).

Footnotes:

(4) Fragments of three Apocryphal books are among extant Qumran texts, with no evidence that they were considered canonical even by the sect that produced them. Philo shows no sign of accepting them either. Sometimes appeal is made to the Greek version of the Old Testament (the “Septuagint”) to suggest “the canon of the Alexandrian Jews was more comprehensive.” F.F. Bruce goes on to say, “There is no evidence that this was so: indeed, there is no evidence that the Alexandrian Jews ever promulgated a canon of scripture” (Canon, pp. 44-45). Indeed, the Septuagint manuscripts we possess were produced by Christians much later, and extant manuscripts differ between themselves, some excluding books of the Apocrypha which Rome accepted, while others included apocryphal books which even Rome denied.

(5) Those who study the history of canonicity will trip themselves up badly if attention is not paid to the varying and unsettled use of terms at this point in church history (late fourth century). For instance, the term “apocrypha” itself carries different import between Athanasius and Jerome. Athanasius spoke of three categories of books: canonical, edifying, and “apocryphal” – meaning heretical works to be avoided altogether. Jerome on the other hand, used the term “apocryphal” for the second category of books, those which are edifying (and Rufinus termed them “ecclesiastical,” since they could be read in the church). The same is true of the early use of the term “canon.” Athanasius appears to be the first to use it in the strict sense that we do today; naturally, such usage was not immediately inculcated by all writers. Sometimes “canonical” was used broadly and indiscriminately to include what other authors more carefully delineated as the books of highest, inspired authority (the church’s standard – “canon”) as well as the edifying or “ecclesiastical” books which could be read in the church. We see this, for instance, at the provincial (non-ecumenical) Third Council of Carthage in 397, which explicitly identifies “the canonical writings” with what “should be read in the church” – and includes the works deemed “edifying” by Athanasius or “apocryphal” by Jerome. Contemporary Roman Catholic scholars recognize the varying use of the term “canonical” by speaking of the apocryphal books as “deuterocanonical.”

(6) Roman Catholic apologists sometimes jump to canonical conclusions from the simple fact that the books of the Apocrypha were copied and included among ancient manuscripts or from the fact than an author draws upon them. But obviously a writer can quote something from a work which he takes to be true without thereby ascribing diving authority to it (for instance, Paul quoting a pagan writer in I Cor. 15:33).

(7) Roman Catholic apologists often misunderstand the Protestant rejection of the Apocrypha, thinking it entails having no respect or use for these books whatsoever. Calvin himself wrote, “I am not one of those, however, who would entirely disapprove the reading of those books”; his objection was to “placing the Apocrypha in the same rank” with inspired Scripture (“Antidote” to the Council of Trent, pp. 67,68). Likewise, Luther placed the Apocrypha in an appendix to the Old Testament in his German Bible, describing them in the title as “Books which are not to be held equal to holy scripture, but are useful and good to read.”

(8) The preceding history and quotations concerning the canon can be pursued in F.F. Bruce, The Canon of Scripture, passim