Middle Knowledge (a concept at the heart of Molinism) is refuted by Dr. James White:

Is There a God?

Article by Sinclair Ferguson (original source here)

Article by Sinclair Ferguson (original source here)

Answer the question “Is there a God?” in around 775 words? Is this perhaps the easiest assignment Tabletalk has ever commissioned, since the answer is so clear? There are no consistent atheists, only people hiding from God. “The heavens declare the glory of God, and the sky above proclaims his handiwork” (Ps. 19:1). God is the inescapable given who undergirds all things.

Or, is this the hardest assignment Tabletalk has ever commissioned? A comprehensive answer might fill an entire library. What follows, then, is only a stray fragment from one chapter in a book in that library.

➝ 1 God the Creator is the only solution to Gottfried Leibniz’s and Martin Heidegger’s ultimate riddle: “Why is there something there, and not nothing?”

Ex nihilo nihil fit—“Nothing comes from nothing.” Let us note that nothing is not a “pre-something”; it is not “something reduced to a minimum.” Nothing is NO thing, no THING. Nothing—a concept impossible for the mind to comprehend precisely because nothing lacks “reality” in the first place. To transform Rene Descartes’; famous dictum Cogito, ergo sum (I think, therefore I am) we can say, Quod cogito, non cogito de nihilo (Because I am, I cannot conceive of nothing).

That leads to another Descartes-esque thought: Quod cogito, ergo non possibile Deus non est (Because I think, therefore it is impossible that God does not exist). The cosmos, my existence, and my ability to reason all depend on the fact that life did not and could not come from nothing, but requires a reasonable and reasoning origin. The contrary (time + chance = reality) is impossible. Neither time nor chance is a pre-cosmic phenomenon.

➝ 2 This God must be the biblical God, for two reasons. The first is that only such a God adequately grounds the physical coherence of the cosmos as we know it.

Second, His existence is the only coherent basis, whether acknowledged or otherwise, for rational thought and communication. Consequently, the nonbeliever of necessity must draw on, borrow from, indeed intellectually steal from a biblical foundation in order to think coherently and to live sanely. Thus, the secular humanist who argues that there are no ultimates must borrow from biblical premises in order to assess anything as in itself right or wrong.

I have recently tried a simple but unnerving experiment, directing my mind to think its way into the assumption that there is no God, and then to explore the implications. I strongly discourage performing this mind experiment. It leads inexorably to a dark place, a mental abyss where nothing in life makes sense, indeed, where there is no possibility of ultimate “sense.”

Here, all that we think of as good, true, rational, intelligible, and beautiful has no substructure to give these concepts coherence. Thus, the nature of everything I am and experience becomes radically deconstructed and disconnected from my consciousness of them. That “consciousness” that seems intelligible is then an unjustifiable fabrication of my own imagination. And then that imagination ceases to have coherence in itself.

In essence, then, my highly complex consciousness becomes merely an inexplicable series of intricate chemical reactions grounded in no rationality and having no inherent meaning. “Meaning” itself in any genuinely transcendent sense is itself a meaningless concept.

As experimenters in the pilgrimage of consistent atheism, we will then conclude that it is the “atheists” who are driven to despair, as they yield to the unbearable conclusions of their premises, who are the only consistent atheistic thinkers with the courage of their convictions. Those who calmly claim to be atheists are unmasked as in fact refusing the conclusion of their professed convictions, repressing what they know deep down to be true (that God is)—the very point Paul makes in Romans 1:18–25.

The novelist Martin Amis recounted a question that the Russian writer Yevgeni Yevtushenko asked Sir Kingsley Amis: “Is it true that you are an atheist?” Amis replied, “Yes. But it’s more than that. You see, I hate Him.” Far from being able to deny the existence of God, he confessed both God’s existence and his own antagonism toward Him.

Amis was not alone. Neither a knight of the Realm, nor any of us, can escape being the imago Dei (however mutilated). We can therefore never deny the Deus of whom we are the imago. For God has placed a burden on us: “He has put eternity into a man’s heart” (Eccl. 3:11). As Augustine said, our hearts are restless until we find our rest in Him.

Why then does the Bible not ask the question, “Is there a God?” Because its first sentence answers it: “In the beginning, God… .”

Genesis 1:1

Liturgical Protestant Worship

Article: 7 Things I Love about Liturgical Protestant Worship by Silverio Gonzalez (original source here)

Article: 7 Things I Love about Liturgical Protestant Worship by Silverio Gonzalez (original source here)

Sometimes the idea of “formal worship” scares people. I hope to make that less scary. The Protestant traditions include Anglicanism, Lutheranism, the Reformed, and Presbyterianism. Although these traditions have important differences, they reflect important similarities in the way they worship. I could feel more or less at home in any of these traditions, so long as they are true to their Reformation heritage. A liturgy is an order of worship in which God gives grace in the gospel and we respond in faith, hope, and love.

1. I love that liturgical Protestant worship is shaped by the Gospel.

Common in Protestant liturgies is a movement from the law of God and our repentance to the Gospel. The Gospel announces our forgiveness and justification. A good liturgy is evangelical in the best sense in that it helps move the congregation through the ordinary patterns of the Christian life. I constantly feel the weight of the week’s sins lifted as I confess my sins in a prayer together with the congregation. Then I hear the pastor preach the gospel, telling me again that my sins are forgiven because of Christ alone.

2. I love that liturgical Protestant worship has specific prayers as part of the service.

In Protestant orders of worship, there is usually a prayer of adoration, a prayer of confession of sin, a pastoral prayer for the needs of the congregation, and a prayer of thanksgiving. Sometimes some of these prayers are expressed in song; other times the entire congregation reads a written prayer. The pastor leads the congregation in these prayers that reflect our unity. Through public prayer, we bear one another’s burdens. When I hear my pastor pray for me, I feel his love for the congregation, and me in particular.

3. I love that liturgical Protestant worship includes lots of Scripture reading throughout the service.

Usually there are readings from the Old and New Testaments, Psalms, Epistles, and Gospels. Sometimes the Psalms are sung. Protestant liturgies include a variety of arrangements and a number of Scripture readings. Hearing so much Scripture read in church is like being washed in God’s Word.

4. I love that liturgical Protestant worship includes the pastor preaching both the law and the gospel from the Bible.

A good sermon doesn’t just tell me about what happened in the past. A good sermon helps me to understand my life as a part of God’s story. A good sermon focuses on what Jesus did—and is doing—to save sinners like me. A good sermon shows me why Jesus had to die. A good sermon shows me how to respond in faith, hope, and love. Protestants preach God’s word of law to humble my proud heart and God’s gospel to show me my savior and remind me how God has promised to work in my life to save me from sin’s penalty and power.

5. I love that liturgical Protestant worship recites creeds.

If you have never been in a church that recites a creed like the Apostles’ Creed, then this is a great reason to visit. When we recite this creed, we recite something that reflects the basics of our faith. The pastor asks, “Congregation, what do you believe?” and we respond with, “I believe in God the Father Almighty….” We confess our common faith together. In this act we connect to the church past, present, and future. We are expressing the one faith that all Christians have sought to maintain for generations.

6. I love that liturgical Protestant worship sings old and new songs.

I love singing old songs, because they remind me of the different cultures and time periods in which God worked. I love singing new songs, because they remind me that the faith is still living, that Christianity is still vibrant today, and that God is still working. Singing new and old songs reminds me that God has promised to gather the nations as his people (Ps. 86:9).

7. I love that liturgical Protestant worship expresses a range of emotions.

Like the Psalms, Protestants know how to mourn, how to praise, how to ask God for our needs, and how to give thanks for what he has already given. When I come to church, I’m not forced to be happy or sad, but I get to express that weird mixture so common to Christians: joy and sorrow, praise and lament, and repentance and faith. I love that I get to express the way I actually feel, and am helped to express the ways I should feel, as I am taught to express the entire range of emotions that are part of the ordinary Christian life.

What Every Christian Should Know

This morning I had the privilege of preaching at a local Church here in Phoenix (while their Pastor was away). My theme was “What Every Christian Should Know” and the base text was 2 Timothy 3:10-17. The service was live-streamed and can be viewed here (I am introduced around the 26 minute, 20 second mark). I hope you find it to be a blessing:

The Message of the Bible

Which Laws Apply?

Article: Which Laws Apply?

Article: Which Laws Apply?

by R.C. Sproul (original source here)

To this day, the question of the role of the law of God in the Christian life provokes much debate and discussion. This is one of those points where we can learn much from our forebears, and John Calvin’s classic treatment of the law in his Institutes of the Christian Religion is particularly helpful. Calvin’s instruction comes down to us in what he calls the threefold use of the law with respect to its relevance to the new covenant.

The law, in its first use, reveals the character of God, and that’s valuable to any believer at any time. But as the law reveals the character of God, it provides a mirror to reflect to us our unholiness against the ultimate standard of righteousness. In that regard, the law serves as a schoolmaster to drive us to Christ. And one of the reasons that the Reformers and the Westminster divines thought that the law remained valuable to the Christian was because the law constantly drives us to the gospel. This also was one of the uses of the law that Martin Luther most strongly emphasized.

Second, the law functions as a restraint against sin. Now, on the one hand, the Reformers understood what Paul says in Romans 7 that in a sense the law prompts people to sin—the more of the law unregenerate people see, the more inclined they are to want to break it. Yet despite that tendency of the law, there still is a general salutary benefit for the world to have the restraints upon us that the law gives. Its warnings and threats restrain people from being as bad as they could be, and so civil order is preserved.

Third, and most important from Calvin’s perspective, is that the law reveals to us what is pleasing to God. Technically speaking, Christians are not under the old covenant and its stipulations. Yet, at the same time, we are called to imitate Christ and to live as people who seek to please the living God (Eph. 5:10; Col. 1:9–12). So, although in one sense I’m not covenantally obligated to the law or under the curse of the law, I put that out the front door and I go around the back door and I say, “Oh Lord, I want to live a life that is pleasing to You, and like the Old Testament psalmist, I can say, ‘Oh how I love Thy law.’” I can meditate on the law day and night because it reveals to me what is pleasing to God.

Let me give you a personal example. Several years ago, I was speaking in Rye, N.Y., at a conference on the holiness of God. After one of the sessions, the sponsors of the conference invited me to someone’s house afterward for prayer and refreshments. When I arrived at the house, there were about twenty-five people in the parlor praying to their dead relatives. To say I was shocked would be an understatement. I said, “Wait a minute. What is this? We’re not allowed to do this. Don’t you know that God prohibits this, and that it’s an abomination in His sight and it pollutes the whole land and provokes His judgment?” And what was their immediate response? “That’s the Old Testament.” I said, “Yes, but what has changed to make a practice that God regarded as a capital offense during one economy of redemptive history now something He delights in?” And they didn’t have a whole lot to say because from the New Testament it is evident that God is as against idolatry now as He was then.

Of course, as we read Scripture, we see that there are some parts of the law that no longer apply to new covenant believers, at least not in the same way that they did to old covenant believers. We make a distinction between moral laws, civil laws, and ceremonial laws such as the dietary laws and physical circumcision. That’s helpful because there’s a certain sense in which practicing some of the laws from the Old Testament as Christians would actually be blasphemy. Paul stresses in Galatians, for example, that if we were to require circumcision, we would be sinning. Now, the distinction between moral, civil, and ceremonial laws is helpful, but for the old covenant Jew, it was somewhat artificial. That’s because it was a matter of the utmost moral consequences whether they kept the ceremonial laws. It was a moral issue for Daniel and his friends not to eat as the Babylonians did (Dan. 1). But the distinction between the moral, civil, and ceremonial laws means that there’s a bedrock body of righteous laws that God gives to His covenant people that have abiding significance and relevance before and after the coming of Christ.

During the period of Reformed scholasticism in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Reformed theologians said that God legislates to Israel and to the new covenant church on two distinct bases: on the basis of divine natural law and on the basis of divine purpose. In this case, the theologians did not mean the lex naturalis, the law that is revealed in nature and in the conscience. By “natural law,” they meant those laws that are rooted and grounded in God’s own character. For God to abrogate these laws would be to do violence to His own person. For example, if God in the old covenant said, “You shall have no other gods before Me,” but now He says, “It’s OK for you to have other gods and to be involved in idolatry,” God would be doing violence to His own holy character. Statutes legislated on the basis of this natural law will be enforced at all times.

On the other hand, there is legislation made on the basis of the divine purpose in redemption, such as the dietary laws, that when their purpose is fulfilled, God can abrogate without doing violence to His own character. I think that’s a helpful distinction. It doesn’t answer every question, but it helps us discern which laws continue so that we can know what is pleasing to God.

Making Sense of Scripture’s ‘Inconsistency’

Article by Tim Keller: Making Sense of Scripture’s ‘Inconsistency’ (original source here)

Article by Tim Keller: Making Sense of Scripture’s ‘Inconsistency’ (original source here)

I find it frustrating when I read or hear columnists, pundits, or journalists dismiss Christians as inconsistent because “they pick and choose which of the rules in the Bible to obey.” Most often I hear, “Christians ignore lots of Old Testament texts—about not eating raw meat or pork or shellfish, not executing people for breaking the Sabbath, not wearing garments woven with two kinds of material and so on. Then they condemn homosexuality. Aren’t you just picking and choosing what you want to believe from the Bible?”

I don’t expect everyone to understand that the whole Bible is about Jesus and God’s plan to redeem his people, but I vainly hope that one day someone will access their common sense (or at least talk to an informed theological adviser) before leveling the charge of inconsistency.

First, it’s not only the Old Testament that has proscriptions about homosexuality. The New Testament has plenty to say about it as well. Even Jesus says, in his discussion of divorce in Matthew 19:3–12, that the original design of God was for one man and one woman to be united as one flesh, and failing that (v. 12), persons should abstain from marriage and sex.

However, let’s get back to considering the larger issue of inconsistency regarding things mentioned in the Old Testament no longer practiced by the New Testament people of God. Most Christians don’t know what to say when confronted about this issue. Here’s a short course on the relationship of the Old Testament to the New Testament.

The Old Testament devotes a good amount of space to describing the various sacrifices offered in the tabernacle (and later temple) to atone for sin so that worshipers could approach a holy God. There was also a complex set of rules for ceremonial purity and cleanness. You could only approach God in worship if you ate certain foods and not others, wore certain forms of dress, refrained from touching a variety of objects, and so on. This vividly conveyed, over and over, that human beings are spiritually unclean and can’t go into God’s presence without purification.

But even in the Old Testament, many writers hinted that the sacrifices and the temple worship regulations pointed forward to something beyond them (cf. 1 Sam. 15:21–22; Pss. 50:12–15; 51:17; Hos. 6:6). When Christ appeared he declared all foods clean (Mark 7:19), and he ignored the Old Testament cleanliness laws in other ways, touching lepers and dead bodies.

The reason is clear. When he died on the cross the veil in the temple tore, showing that he had done away with the the need for the entire sacrificial system with all its cleanliness laws. Jesus is the ultimate sacrifice for sin, and now Jesus makes us clean.

The entire book of Hebrews explains that the Old Testament ceremonial laws were not so much abolished as fulfilled by Christ. Whenever we pray “in Jesus name” we “have confidence to enter the Most Holy Place by the blood of Jesus” (Heb. 10:19). It would, therefore, be deeply inconsistent with the teaching of the Bible as a whole if we continued to follow the ceremonial laws.

Law Still Binding

The New Testament gives us further guidance about how to read the Old Testament. Paul makes it clear in places like Romans 13:8ff that the apostles understood the Old Testament moral law to still be binding on us. In short, the coming of Christ changed how we worship, but not how we live. The moral law outlines God’s own character—his integrity, love, and faithfulness. And so everything the Old Testament says about loving our neighbor, caring for the poor, generosity with our possessions, social relationships, and commitment to our family is still in force. The New Testament continues to forbid killing or committing adultery, and all the sex ethic of the Old Testament is re-stated throughout the New Testament (Matt. 5:27–30; 1 Cor. 6:9–20; 1 Tim. 1:8–11). If the New Testament has reaffirmed a commandment, then it is still in force for us today.

The New Testament explains another change between the testaments. Sins continue to be sins—but the penalties change. In the Old Testament sins like adultery or incest were punishable with civil sanctions like execution. This is because at that time God’s people constituted a nation-state, and so all sins had civil penalties.

But in the New Testament the people of God are an assembly of churches all over the world, living under many different governments. The church is not a civil government, and so sins are dealt with by exhortation and, at worst, exclusion from membership. This is how Paul deals with a case of incest in the Corinthian church (1 Cor. 5:1ff. and 2 Cor. 2:7–11). Why this change? Under Christ, the gospel is not confined to a single nation—it has been released to go into all cultures and peoples.

Once you grant the main premise of the Bible—about the surpassing significance of Christ and his salvation—then all the various parts of the Bible make sense. Because of Christ, the ceremonial law is repealed. Because of Christ, the church is no longer a nation-state imposing civil penalties. It all falls into place. However, if you reject the idea of Christ as Son of God and Savior, then, of course, the Bible is at best a mishmash containing some inspiration and wisdom, but most of it would have to be rejected as foolish or erroneous.

So where does this leave us? There are only two possibilities. If Christ is God, then this way of reading the Bible makes sense. The other possibility is that you reject Christianity’s basic thesis—you don’t believe Jesus is the resurrected Son of God—and then the Bible is no sure guide for you about much of anything. But you can’t say in fairness that Christians are being inconsistent with their beliefs to follow the moral statements in the Old Testament while not practicing the other ones.

One way to respond to the charge of inconsistency may be to ask a counter-question: “Are you asking me to deny the very heart of my Christian beliefs?” If you are asked, “Why do you say that?” you could respond, “If I believe Jesus is the resurrected Son of God, I can’t follow all the ‘clean laws’ of diet and practice, and I can’t offer animal sacrifices. All that would be to deny the power of Christ’s death on the cross. And so those who really believe in Christ must follow some Old Testament texts and not others.”

Presuppositional Apologetics Series

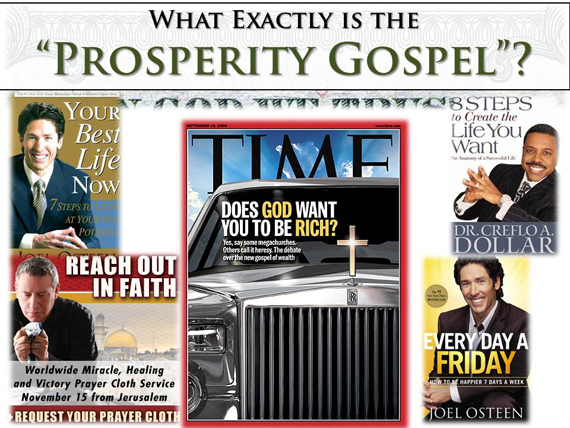

Exposing The So Called “Prosperity Gospel”

On Friday, Sept. 8th I am scheduled to team up with Costi Hinn (Benny Hinn’s nephew, now converted and a Reformed Baptist Pastor in California) on Chris Arnzen’s “Iron Sharpens Iron” broadcast. The show’s theme for the two hours will be to bring the light of God’s word in exposing the Word of Faith movement. Please be in prayer that many will be drawn out of deception. Here’s a recent article Pastor Costi wrote:

On Friday, Sept. 8th I am scheduled to team up with Costi Hinn (Benny Hinn’s nephew, now converted and a Reformed Baptist Pastor in California) on Chris Arnzen’s “Iron Sharpens Iron” broadcast. The show’s theme for the two hours will be to bring the light of God’s word in exposing the Word of Faith movement. Please be in prayer that many will be drawn out of deception. Here’s a recent article Pastor Costi wrote:

Article: The Prosperity Gospel: A Global Epidemic by Costi Hinn (original source here)

Prosperity is hot topic in the church. Does God care if a pastor drives a nice car or lives in a nice home? Does God command that all who follow Him take a vow of poverty and starve their families in a protest of earthly comfort? Bible teachers sell millions of books and accumulate mass amounts of wealth, are they in the same league as other wealthy preachers? Some men will have deep convictions about attaining any measure of wealth, while others will be content use their wealth to give back to their church. Some will use their wealth to fund a child’s college tuition, or even scholarship a seminary student. Others will invest their wealth with the goal of giving even more away in the future.

Stewardship comes in all shapes and sizes but one thing doesn’t—God’s ability to weigh a man’s heart and motives. It is a man’s heart that God is most interested in and the gospel a man proclaims that God will judge most. When Heaven’s final bell rings and every man is recompensed according to his deeds, God will have the final say. The issue will not be whether that pastor took home a six-figure salary; the issue will be what that man taught and wrote while representing the gospel of Jesus Christ.

In this article, the prosperity gospel is placed front and center as one of the deadliest teachings in the world today. It has attached itself to the Bible, and to Jesus Christ—though it has no business doing so. Billions chase after it in search of stability and hope. Yet, all those who live and die trusting in the prosperity gospel for salvation will be left wanting in both this life, and the next.

What is Prosperity Gospel Theology?

A very basic definition of the prosperity gospel can be described as this: God’s plan is for you to live your best life now. Health, wealth, and happiness are guaranteed on Earth for all who follow Jesus. Heaven is simply the eternal extension of your temporal blessings. The prosperity gospel’s theological foundation can be traced to at least three twisted versions of biblical truths. Prosperity preacher’s twist these in order to legitimize their version of the gospel.

Christ’s Atonement Means Abundant Life Now

The Bible clearly teaches that Christ died to atone for our sin (Isaiah 53) and that because of what He accomplished through His death and resurrection, we’ll experience the abundant life that He came to give us (John 10:10). Though we enjoy some benefits of the atonement now—such as the forgiveness of our sins and assurance of salvation—His atonement guarantees eternal promises that won’t be fully be realized until Heaven. We’ll receive a glorified body, there will be no death, no sin, no pain, no suffering, and no disease! Those are just a few of the eternal benefits of the atonement. Best of all, we’ll enjoy perfect fellowship with our God forever more.

The Bible clearly teaches that Christ died to atone for our sin (Isaiah 53) and that because of what He accomplished through His death and resurrection, we’ll experience the abundant life that He came to give us (John 10:10). Though we enjoy some benefits of the atonement now—such as the forgiveness of our sins and assurance of salvation—His atonement guarantees eternal promises that won’t be fully be realized until Heaven. We’ll receive a glorified body, there will be no death, no sin, no pain, no suffering, and no disease! Those are just a few of the eternal benefits of the atonement. Best of all, we’ll enjoy perfect fellowship with our God forever more.

Prosperity preachers teach that health and wealth were “paid for” in the atonement—just like sin. Therefore, this twisted interpretation allows them to teach people to expect complete healing, monetary riches, and total victory in every area of their earthly life. Instead of telling people to put faith in Jesus Christ and excitedly await their best life in heaven, they offer an empty gospel that promises people their best life now.

God’s Covenant with Abraham Means Inheritance Now

There’s an old children’s song that goes something like this: “Father Abraham had many sons. Many sons had Father Abraham. I am one of them, and so are you. So let’s just praise the Lord!” It’s used by many faithful Christians as a way to teach children about the great joy associated with God’s covenant with Abraham. Specifically speaking, the Abrahamic covenant (Genesis 12:1-3) has much to do with redemption, and God’s promises to His people. However, prosperity preacher’s use the covenant as a means to promise an inheritance (usually land and money) for their followers now. This has become their most common use for it.

In the prosperity gospel, God’s covenant with Abraham is littered with statements like, “If you’ll sow a seed of faith like Abraham, God will bless you”, or “If you speak it and live it by faith like Abraham, God will prosper you.” These type of statements are a way to present any temporal or eternal inheritance that awaits God’s people as a blanket guarantee.

If these twisted versions of the Abrahamic covenant were true, then the millions who trust in the prosperity gospel would become millionaires and land-owners overnight. Thus far, it is mainly the prosperity preachers who are benefitting from the offerings of those they deceive.

Faith is a Force You Can Use to Control God

The Bible teaches that Christians are justified by faith (Romans 5:1), that Christians overcome the world through faith (1st John 5:5), and that Christians live by faith because of what Christ has done (Galatians 2:20). The list of verses on the blessings of faith is endless! Faith pleases God, is directly related to salvation, and is the evidence of trust in God for the believer.

Prosperity gospel preachers depart from this orthodox teaching on faith when they teach that faith is a force you can use to get what you want from God. In other words, you were able to obtain salvation and justification by faith, so why can’t you obtain a Ferrari the same way? Prosperity theology is centered on the notion that right believing, right thinking, and right speaking are all linked with faith in order to create physical blessings. This is where the word of faith movement also hybrids with the prosperity gospel.

How Did the Prosperity Gospel Get So Popular?

Long before the Catholic Church was selling indulgences, the correlation between ministry, money, and manipulation was crystal clear. The Bible even describes Simon the Sorcerer (Acts 8:9-24) as a magician who thought he could buy the gift of God with money. Specifically speaking, the modern day roots of the prosperity gospel go back approximately seventy years. It was during the 1950’s that this divergent gospel pioneered its way into the mainstream evangelical scene and nobody at the time could have imagined that it would spread across the globe.

Born in 1918, Granville “Oral” Roberts was, in many ways, the lead prosperity pioneer. He went from being a local pastor, to building a multimillion dollar empire based on one major theological premise: God wanted people to be healthy and wealthy.

Oral Roberts didn’t mince words about his version of Jesus or the gospel. He adamantly taught and defended his belief that Jesus’ highest wish is for us to prosper materially and have physical health equal to His peace and power in our soul. He twisted the Bible to make his point and would teach that it was Jesus who said, in 3rd John 1:2, “Beloved, I wish above all things that thou may prosper and be in health, even as thy soul prospereth,” when in fact that was the Apostle John’s loving way of greeting his readers at the time. John’s greeting is comparable to the first line of many of our modern day e-mails that begin with, “Hi! I hope everything is going well for you.” Continue reading