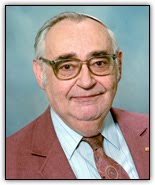

Dr. Roger Nicole (December 10, 1915 – December 11, 2010[1]) was a native Swiss Reformed Baptist theologian. He was an associate editor for the New Geneva Study Bible, assisted in the translation of the New International Version, and was a founding member of both the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy and the Evangelical Theological Society, serving as president of the latter in 1956.

Dr. Roger Nicole (December 10, 1915 – December 11, 2010[1]) was a native Swiss Reformed Baptist theologian. He was an associate editor for the New Geneva Study Bible, assisted in the translation of the New International Version, and was a founding member of both the International Council on Biblical Inerrancy and the Evangelical Theological Society, serving as president of the latter in 1956.

The following excerpt is a transcript from a teaching he conducted decades ago entitled “The Five Points of Calvinism”:

Then comes the third point which is sometimes called Limited Atonement. And here I wax warm because I think that is a complete misnomer. The others I am willing to live with. “Limited Atonement” I cannot live with because that is a total misrepresentation of what we mean to say.

The purpose of using that expression is that the atonement is not universal in the sense that Christ died for every member of the race, in the same sense in which He died for those who will be redeemed. Therefore the purpose of the atonement is restricted to the elect and not spread to the universality of mankind. This is what is meant by “Limited”.

But the problem is that anyone who does not hold that Christ will in fact save everybody has a “limited atonement”. Anyone who says there will be some people saved and other people lost, has to say the atonement does not function for the universality of mankind.

Now some of the people limit it in breadth; that is, they say, the Lord Jesus Christ died for the redeemed and He sees to it that the redeemed are therefore saved. So that there is a certain group of mankind, a particular group, which is the special object of the redemptive love and substitutionary work of Jesus Christ and toward this group then, Christ sees to it that His work is effective and brings about their salvation. And while the remainder of mankind may gain some benefits from the work of Christ, they are however, not encompassed in the same way in His design, as were those whom the Father gave Him. This is one way of limiting it, you may limit it in breadth, if I may put it that way.

The other people who say “Christ died for everybody in the same way”, have to recognize that some people for whom Christ died, at the end are lost, so that the death of Christ does not ensure the salvation of those for whom He died. The effect is therefore that they limit the atonement in depth. The atonement is ineffective. It does not secure the salvation of the people for whom it is intended. And so in some way, the will of God and the redemptive love of Jesus Christ are frustrated by the resistance and the wicked will of men who resist Him and do not accept His grace. So that salvation really consists on the work of Christ plus acceptance or non-resistance or some ingredient of one kind or another that some people add. And it is this ingredient which really constitutes the difference between being saved and being lost.

No one who says “at the end there will be some people saved and other people lost” can really in honesty speak of an “Unlimited Atonement”, and therefore I for one am not happy to go under the banner of “Limited Atonement” as if Calvinists and myself were the ones who wickedly emasculate and mutilate the great scope and beauty of the love and redemption of Jesus Christ.

This is not really a question of limit. This is a question of purpose.

And so we ought to talk about “Definite Atonement.” There is a definite purpose of Christ in offering Himself. Substitution that is not a ‘blanket’ substitution; but a substitution that is oriented specifically to the purpose for which He came into this world, which is to save and redeem those whom the Father has given Him.

Another term that is appropriate, although perhaps less precise is the term “Particular Redemption”, for the redemption of Christ is a particular one, which accomplishes what it purposes. The alternative is that Christ redeemed no one in particular.

Now if we change that language I think we put ourselves away from the very unpleasant onus of being the one who seems to be in the business of restricting the scope of the love of Christ.

If I am ready to say my position is that of “Limited Atonement”, my opponent will come and say, “You believe in Limited Atonement but I believe in Unlimited Atonement” – he seems to be the one who exalts the grace of God.

Now use my words and see what happens.

I say, “I believe in Definite Atonement”. What can my opponent say?

He says, “Well I believe in Indefinite Atonement.”

Now if they want to use the language, I have no opportunity to do anything but to protest. But if I have the choice to use a language to represent my position I certainly do not want to put myself at the psychological disadvantage from the start. And the term “Definite Atonement” you will find in very fine writers like John Owen and William Cunningham of Scotland, and Warfield and others, is a much more accurate representation of precisely what the Reformed position holds. Let us abandon that expression “Limited Atonement” which disfigures the Calvinistic doctrine of grace in the work of Christ. I feel rather strongly on that, as you know.

Mike Riccardi has served on staff at Grace Community Church since 2010. He currently serves as the Pastor of Local Outreach Ministries, which includes overseeing Fundamentals of the Faith classes, six foreign language outreach Bible studies, and evangelism in nearby jails, rehab centers, and in the local neighborhood. Mike earned his B.A. in Italian and his M.Ed. in Foreign Language from Rutgers University, and his M.Div. and Th.M. from The Master’s Seminary. He also has the privilege of serving alongside Phil Johnson as co-pastor of GraceLife, a Sunday morning adult fellowship group at Grace Church.

Mike Riccardi has served on staff at Grace Community Church since 2010. He currently serves as the Pastor of Local Outreach Ministries, which includes overseeing Fundamentals of the Faith classes, six foreign language outreach Bible studies, and evangelism in nearby jails, rehab centers, and in the local neighborhood. Mike earned his B.A. in Italian and his M.Ed. in Foreign Language from Rutgers University, and his M.Div. and Th.M. from The Master’s Seminary. He also has the privilege of serving alongside Phil Johnson as co-pastor of GraceLife, a Sunday morning adult fellowship group at Grace Church.  Article by Dr. Jared Hood – (original source

Article by Dr. Jared Hood – (original source  What did John Calvin believe concerning limited Atonement? Many say that Calvin did not. Dr. Nicole addresses this question with great care.

What did John Calvin believe concerning limited Atonement? Many say that Calvin did not. Dr. Nicole addresses this question with great care. Article by TurretinFan: Three Days and Three Nights – Hebrew Idiom for Three Consecutive Calendar Days (original source

Article by TurretinFan: Three Days and Three Nights – Hebrew Idiom for Three Consecutive Calendar Days (original source  This excerpt is adapted from The Truth of the Cross by R.C. Sproul

This excerpt is adapted from The Truth of the Cross by R.C. Sproul