From the 2006 Together for the Gospel Conference, R.C. Sproul outlines the biblical doctrine of justification by faith alone over against the teaching of the Roman Catholic Church.

Category Archives: Five Solas

The Bible and the Church

In an article entitled, “Is the Church over the Bible or is the Bible over the Church?” Michael J Kruger if one were to respond to each and every erroneous claim on the internet there would be time for little else. But every now and then, an article combines so many misconceptions about the canon is a single place, that a response is warranted. This is the case with the recent article, “There is No ‘Bible’ in the Bible,” by Fr. Stephen Freeman.

In an article entitled, “Is the Church over the Bible or is the Bible over the Church?” Michael J Kruger if one were to respond to each and every erroneous claim on the internet there would be time for little else. But every now and then, an article combines so many misconceptions about the canon is a single place, that a response is warranted. This is the case with the recent article, “There is No ‘Bible’ in the Bible,” by Fr. Stephen Freeman.

Freeman, part of the Orthodox Church in America, has made what is essentially a Roman Catholic argument for the canon (but missing some key portions, as we shall see). His basic claim is that the Bible–as something that is an authority over the church–is a modern, post-Reformation invention. In reality, he claims, the church is the highest authority and the Bible is merely one of many tools used by the church.

Perhaps the best way to respond to Freeman’s article is just to quote it line by line (in italics below), offering a response to each statement as we go. For space reasons, we will not be able to cover every one of his claims, but we will cover the major ones.

1. The word “Bible” simply means “book.” Thus, it is a name that means “the Book.” It is a particularly late notion if for no other reason than that books are a rather late invention.

Freeman makes the claim here that the “Bible” must be late, because books are a late invention. This is stunning to say the least given that Israel had been using books as Scripture for more than a thousand years before Christ was even born. Moreover, early Christianity was a very “bookish” culture right from the start, with a keen interest in reading, producing, and copying books. For more on this point see my article here. Thus, books were not at all a foreign idea to the early Christian faith.

2. There are examples of bound folios of the New Testament dating to around the 4th century, but they may very well have been some of the earliest examples of such productions.

By the term “bound folios” I assume Freeman is referring to early Christian codices that contained multiple books in the same volume. If so, then the “earliest examples” do not derive from the fourth century, but much earlier. At the end of the second century/early third century we have all four gospels in a single volume (P4-64-67, P45), and most, if not all, of Paul’s epistles in a single volume (P46). These codices demonstrate a book consciousness very early in the life of the church.

But, perhaps Freeman mentions the fourth century because he is referring to codices that contain all 27 NT books. He is correct that the fourth century is the first instance of all 27 books bound together (e.g. Codex Sinaiticus; see photo above) But, one does not need all 27 books in a single volume in order to establish that the early church had a canon of Scripture. Books don’t need to be physically bound together in order to viewed as part of a scriptural collection. Indeed, this was precisely the case with the OT books. Individual OT books were often kept in separate rolls, even though they were clearly viewed as part of a larger biblical corpus.

3. The “Bible,” a single book with the whole of the Scriptures included, is indeed modern. It is a by-product of the printing press, fostered by the doctrines of Protestantism.

The discussion above has already refuted the notion that a complete NT canon does not come around until the printing press. In addition, Freeman does not mention the fact that we can determine the extent of the church’s canon in other ways besides the physical book. Early Christians drew up lists of their books from quite an early time. For instance, Origen lists all 27 books in a single list in the third century (see article here). Would Freeman suggest that Origen’s NT canon is simply the “by-product of the printing press fostered by the doctrines of Protestantism”? Continue reading

The Five Solas (Revisited)

Sola Scriptura (Rightly Understood)

Patrick Schreiner writes:

Sola scriptura is a Reformation principle of the sufficiency of Scripture as our supreme authority in spiritual matters. Unfortunately, it is a doctrine commonly misunderstood.

Often when described by contemporary supporters and contemporary opponents the view of sola scriptura differs from what one finds in the writings of the Reformers. In other words, what is set up to sink as a misguided principle or to hoist as a banner is not sola scriptura but solo scriptura.

The major issue underlying sola scriptura is relationship between Scripture and tradition. But some who propound sola scriptura do so in the sense that Scripture clashes with tradition.

Nevertheless as Timothy Ward notes “the early fathers of the church would simply not have understood the notion of Scripture clashing with tradition” (143).

Ward then introduces three different views of tradition found in the writing of Heiko Oberman.

Tradition I:

Tradition I is the view that tradition is a tool to aid in the faithful interpretation of Scripture, expounding the primary teachings of Scripture.

Tradition II:

Tradition II asserts there are two distinct sources of divine revelation, Scripture and church tradition, with the latter being handed down either orally or through customary church practices.

Tradition o:

Tradition o exalts the the individual’s interpretation of Scripture over that of the corporate interpretation of past generations of Christians.

The Reformers saw themselves as propounding Tradition I in response to both Tradition II (Roman Catholic Church) and Tradition o (Anabaptists). They did not see themselves as introducing some new teaching about the relationship between Scripture and tradition, but rather a principle most of the church fathers had taught all along.

But sometimes being so far removed from the situation or simply hearing soundbites of what sola scriptura is causes one to slide into Tradition o. Keith Mathison argues that since the eighteenth century American evangelicalism, especially in its popular forms, has largely adopted something close to Tradition o or solo scriptura, while wrongly imagining they are remaining faithful to Luther and Calvin.

The Reformers’ conviction of sola scriptura is the conviction that Scripture is the only infallible authority, the only supreme authority. Yet it is not the only authority, for the creeds and the church’s teaching function as important subordinate authorities, under the authority of Scripture (147).

Or in the famously used phrase, “our final authority is Scripture alone, but not a Scripture that is alone.”

Seven Hours of Dividing Lines

Throughout 2014, while Dr. James White has been away on various ministry trips, I have had the distinct honor and privilege of guest-hosting his “Dividing Line” broadcasts. This allowed me the opportunity of teaching on some major doctrines at the heart of the Christian faith. Here are the youtube videos (all in one place):

Hour 1. “Law and Gospel.”

Hour 2. “The Five Solas of the Reformation.”

Hour 3. The “T” in the TULIP, “Total Depravity.”:

Hour 4. The “U” in the TULIP, “Unconditional Election.”

Hour 5. The “L” in the TULIP, “Limited Atonement.”

Hour 6. July, 2014: Continuing on from Dividing Line broadcasts earlier in the year, here is teaching on the “I” in the TULIP, “Irresistible Grace.”

Hour 7. July, 2014: The conclusion of the TULIP series – the Perseverance (or Preservation) of the Saints:

The Five Questions the Five Solas Answer

Jesse Johnson is the Teaching Pastor at Immanuel Bible Church in Springfield, VA. In an article entitled, “5 questions and the 5 solas” he meaning that the priests and laity lived in practically two separate worlds. There was no concept of church membership, corporate worship, preaching, or Bible reading in the churches. And as far as doctrine was concerned, there was no debate—the creeds and declarations from Rome (and soon to be Avignon) were the law.

Things had been this way for six hundred years. In a world where life expectancy was in the 30’s, that is essentially the same as saying that the church had been in the dark forever.

But if you fast-forward to the end of the 1500’s, all of that had been turned on its head. The absolute nature of the Pope’s rule and vanished—in large part owing to the Babylonian Captivity of the church (the 40 year period were two rival popes both ruled, and both excommunicated each other—finally to both be deposed by a church council). Church councils themselves had contradicted themselves so many times that their own authority was openly ridiculed. The Holy Roman Empire was no longer relevant, and the political world had simply passed the Pope by.

Protestants found themselves in the wake of this upheaval, and there was one major question to be answered: what, exactly, was this new kind of Christian? What did a Protestant believe? The reformation had followed similar and simultaneous tracks in multiple countries, yet at the end of it all the content of Protestantism was pretty much the same. On the essentials, German, English, Swiss, and Dutch Protestants all stood for the same theology. But what was it?

It was easy to understand the beliefs of Catholicism—all one had to do was look at their creeds and the declarations from their councils. But Protestants were so named precisely because they were opposed to all that. So what council would give them their beliefs then?

This is where the five solas came from. These were five statements about the content of the Protestant gospel, and by the end of the 1500’s, these were the terms which identified Protestantism. These five phrases are not an extensive statement on theology, but instead served simply as a way to explain what the content of the gospel was to which Protestants held.

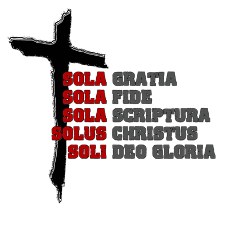

Sola Fide—Faith alone

Solus Christus—Christ alone

Sola Scriptura—Scripture alone

Sola Gratia—Grace alone

Soli Deo Gloria—God’s glory alone

These five solas still live on to this very day. They define what the gospel is for evangelicals worldwide, and also provide a helpful summary—a cheat sheet even—of what marks the true gospel from a religion of works. But historically, these five solas make the most sense when viewed from the perspective of answering the question: what do Protestants believe? In fact, each one of these five is an answer to a particular question:

What must I do to be saved? Sola Fide

The gospel is not a religion of works, but a religions of faith. You can’t do anything to be saved—rather, God saves you on the basis of your faith, which is itself on the basis of the work of Christ on your behalf. Protestants believe that you don’t work for your salvation, and that nobody is good enough to deserve salvation. But thankfully salvation does not come on the basis of works but instead on the basis of faith.

Sola fide declares that In addition to faith, you can do absolutely nothing in order to be saved.

What must I trust? Solus Christus

In a world with deposed Popes in the unemployment line, this question has profound importance. Keep in mind that for six hundred years, nearly every European would have answered that question by pointing at the sacraments. You trust them for your salvation. Perhaps some would point you to the church, the priest, of even to Jesus himself. But only a Protestant would say “trust Jesus alone.”

Solus Christus is a simple declaration that salvation is not dispensed through Rome, priests, or sacraments. There is no sense in putting hope in extreme unction, purgatory, or an indulgence. Instead it comes through Jesus alone.

What must I obey? Sola Scriptura

When the Council of Constance deposed both Popes, this question took on a sense of urgency. If a council is greater than a Pope, then does one have to obey the Pope at all, or is it better to simply submit yourself to the church as a whole? Are believers compelled to obey priests in matters of faith?

Sola Scriptura says “no.” In matters of faith, believers are compelled by no other authority than that of Scripture. There is no room for a mixture of history and tradition—those cannot restrain the flesh and they cannot bind the conscience. Instead, believers’ only ultimate authority is the Bible.

What must I earn? Sola Gratia

Is there any sense in which a person must earn salvation? For the Protestant, the answer is obvious: NO! Salvation is of grace…ALONE. It is not by work or merit. God didn’t look down the tunnel of time and see how you were going to responded to the gospel, then rewind the tape and choose you. He does not save you in light of what you did, are doing, or will do in the future. Instead, his salvation is based entirely upon his grace.

What is the point? Soli Deo Gloria

What is the point of the Reformation? Why are these doctrinal differences worth dividing over? Because people were made for one reason, and one reason alone: to glorify God. God is glorified in his creation, in his children, in the gospel, and most particularly in his son. The highest calling on a persons’ life (indeed, the only real calling in a person’s life) is that he would glorify God in all he does. Nevertheless, we always fail to do that. Yet God saves us anyway through the gospel.

Soli Deo Gloria is a reminder that by twisting the gospel or by adding works to the gospel, a person is actually missing the glory that comes through a gospel of grace and faith, through Jesus, and described by Scripture. The first four questions really function like tributaries, and they all flow to this body—God’s glory.

The Five Solas of the Reformation

Tota Scriptura

Dr. R. C. Sproul writes:

In centuries past, the church was faced with the important task of recognizing which books belong in the Bible. The Bible itself is not a single book but a collection of many individual books. What the church sought to establish was what we call the canon of sacred Scripture. The word canon comes from a Greek word that means “standard or measuring rod.” So the canon of sacred Scripture delineates the standard that the church used in receiving the Word of God. As is often the case, it is the work of heretics that forces the church to define her doctrines with greater and greater precision.

We saw the Nicene Creed as a response to the heresy of Arius in the fourth century, and we saw the Council of Chalcedon as a response to the fifth-century heresies of Eutyches and Nestorius, with respect to the church’s understanding of the person of Christ. In like manner, the first list of canonical books of the New Testament that we have was produced by a heretic named Marcion.

We saw the Nicene Creed as a response to the heresy of Arius in the fourth century, and we saw the Council of Chalcedon as a response to the fifth-century heresies of Eutyches and Nestorius, with respect to the church’s understanding of the person of Christ. In like manner, the first list of canonical books of the New Testament that we have was produced by a heretic named Marcion.

Marcion’s New Testament was an expurgated version of the original biblical documents. Marcion was convinced that the God of the Old Testament was at best a demiurge (a creator god who is the originator of evil) who in many respects is defective in being and character. Thus, any reference to that god in the New Testament in a positive relationship to Jesus had to be edited out. And so we receive from Marcion a bare-bones profile of Jesus and His teaching, divorced from the Old Testament. Over against this heresy, the church had to define the full measure of the apostolic writings, which they did in establishing the New Testament and Old Testament canon.

Another crisis emerged much later in the sixteenth century, in the midst of the Protestant Reformation. Though the central debate, what historians call the material cause of the Reformation, focused on the doctrine of justification, the underlying dispute was the secondary issue of authority. In Luther’s defense of sola fide or faith alone, he was reminded by the Roman Catholic Church that she had already made judgments in her papal encyclicals and in her historical documents in ways that ran counter to Luther’s theses. And in the middle of that controversy, Luther affirmed the Protestant principle of sola Scriptura, namely that the conscience is bound by sacred Scripture alone, that is, the Bible is the only source of divine, special revelation that we have. In response, the Roman Catholic Church at the fourth session of the Council of Trent declared that God’s special revelation is contained both in sacred Scripture and in the tradition of the church. This position, called a dual-source view of revelation, was reaffirmed by subsequent papal encyclicals. And so we see the dispute between Scripture alone versus Scripture plus tradition. In that controversy, the issue had to do with something that was an addition to the Bible, namely, the church’s tradition.

Since that time, the opposite problem has emerged, and that is not so much the question of what is added to Scripture, but rather what has been subtracted from it. We face now an issue not of Scripture addition but of Scripture reduction. The issue that we face in our day is not merely the question of sola Scriptura but also the question of tota Scriptura, which has to do with embracing the whole counsel of God as it is revealed in the entirety of sacred Scripture. There have been many attempts in the last century to seek a canon within the canon. That is to say, restricted portions of Scripture are deemed as God’s revelation, not the whole of Scripture. In this case, we have seen movements that have been described by historians as neo-Marcionite. That is, the activity of canon reduction sought by the heretic Marcion in the early church has now been replicated in our day.

Perhaps most famous for this in the twentieth century was the German theologian Rudolf Bultmann, who made a significant distinction between what he called kerygma and myth. He taught that the Scriptures contained truths of historical value and of theological value that were salvific in their content, but that those truths were hidden and contained within a husk of mythology. For the Bible to be relevant to modern man, it must be demythologized. The husks must be broken in order that the kernel of truth buried under the mythological husk can be brought to the surface.

Beyond the radical reductionism of Bultmann, we have seen more recently attempts among professing evangelicals, and even within the Reformed community, to seek a different type of reduction of Scripture. We have seen views of so-called “limited inspiration” or “limited inerrancy.” That is to say, the Spirit’s inspiration of the Bible is not holistic, but rather is limited to matters of faith and doctrine. In this scenario, proponents suggest we can distinguish between doctrinal matters that are of divine origin and what the Bible teaches in matters of science and history, and, in some cases, ethics. Therefore, there are portions within the Bible that are not equally inspired by God. In this case, we see the reappearance of a canon within a canon. The problem that arises is a serious one. Perhaps most severe is the question, who is it who decides what part of the Bible really belongs to the canon? Once we remove ourselves from a view of tota Scriptura, we are free then to pick and choose what portions of Scripture are normative for Christian faith and life, just like picking cherries from a tree.

To do this we would have to revisit the teaching of Jesus, wherein He said that man does not live by bread alone but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God. We would have to change it, to have our Lord say that we do not live by bread alone but by only some of the words that come to us from God. In this case, the Bible is reduced to the status where the whole is less than the sum of its parts. This is an issue that the church has to face in every generation, and it has reappeared today in some of the most surprising places. We’re finding, in seminaries that call themselves Reformed, professors advocating this type of canon within the canon. The church must say an emphatic “no” to these departures from orthodox Christianity, and she must reaffirm her faith not only in sola Scriptura, but in tota Scriptura as well.

Sola Scriptura and the Reformed Confessions

The Martin Luther was already in hot water with the pope after having posted his Ninety-Five Theses the previous year. But he made things considerably worse for himself when, in a debate with Dominican Cardinal Cajetan, he asserted that the pope could and had erred. He turned up the heat considerably in the summer of 1519 when he confessed to Johannes von Eck that not only could popes and councils err, they had erred grievously in condemning John Huss.

The Martin Luther was already in hot water with the pope after having posted his Ninety-Five Theses the previous year. But he made things considerably worse for himself when, in a debate with Dominican Cardinal Cajetan, he asserted that the pope could and had erred. He turned up the heat considerably in the summer of 1519 when he confessed to Johannes von Eck that not only could popes and councils err, they had erred grievously in condemning John Huss.

So was born the Protestant doctrine of sola Scriptura. It was not that Luther despised church authority. He merely recognized that Scripture alone was inerrant and infallible, and therefore only Scripture possessed absolute normative authority. This principle is codified in several sixteenth century Reformed confessions which R. C. Sproul excerpts in the first chapter of his book, Scripture Alone.

The Theses of Berne (1528):

The church of Christ makes no laws or commandments without God’s Word. Hence all human traditions, which are called ecclesiastical commandments, are binding upon us only in so far as they are based and commanded by God’s Word. (Sec. 2)

The Geneva Confession (1536):

First we affirm that we desire to follow Scripture alone as a rule of faith and religion, without mixing it with any other things which might be devised by the opinion of men apart from the Word of God, and without wishing to accept for our spiritual government any other doctrine than what is conveyed to us by the same Word of God, and without addition or diminution, according to the command of our Lord. (Sec. 1)

The French Confession of Faith (1559):

We believe that the Word contained in these books has proceeded from God, and receives itls authority from God alone, and not from men. And inasmuch as is the rule of all truth, containing all that is necessary for the service of God and for our salvation it is not lawful for men, even for angels, to add to it, to take away from it, or to change it. Whence it follows that no authority whether of antiquity, or custom or numbers, or human wisdom, or judgments, or proclamations, or edicts, or decrees, or councils or visions, or miracles, should be opposed to these holy Scriptures, but on the contrary, all things should be examined, regulated and reformed according to them. (Art. 5)

The Belgic Confession (1561):

We receive all these books, and these only as holy and confirmation of our faith; believing, without any doubt, all things contained in them, not so much because the church receives, and approves them as such, but more especially because the Holy Ghost witnessed in our hearts that they are from God, whereof they carry the evidence in themselves (Art. 5).

Therefore we reject with all our hearts whatsoever doth not agree with this infallible rule (Art. 7).

The Second Helvic Confession (1566):

Therefore, we do not admit any other judge that Christ himself, who proclaims by the Holy Scriptures what is true, what is false, what is to be followed, or what is to be avoided (chap. 2).

— R. C. Sproul, Scripture Alone (P&R Publishing Company, 2005), 18–20.

Necessity v. Sufficiency

Many will speak of the need for grace; the Bible teaches that we not only need grace, but that God’s grace is sufficient to save.

Many will speak of the need for grace; the Bible teaches that we not only need grace, but that God’s grace is sufficient to save.

Many will speak of the need for faith; the Bible teaches that we are justified by faith alone.

Many will say that Christ saves; the Bible teaches that Christ is the only and all sufficient Savior.

Many will appeal to the Scripture; the Bible teaches that Scripture alone is God breathed – the sole infallible rule of faith for the people of God.

Many speak of God’s glory, but that glory is diminished unless God Himself does the saving, all by Himself.

The dividing line of the Gospel has always been NECESSITY v. SUFFICIENCY:

Grace v. Grace Alone

Faith v. Faith Alone

Christ v. Christ Alone

Scripture v. Scripture Alone

The Glory of God v. the Glory of God Alone