Sandy Grant is the senior minister at St Michael’s Anglican Cathedral in Wollongong, New South Wales, Australia. I do not know him at all, other than the fact that he serves on the writer panel at solapanel.org. However, I did find myself in full agreement with him on this article. Pastor Grant writes:

Recently on a feedback card at church, someone commented: “I thought Jesus didn’t descend into hell! Just that he suffered the death we deserved.”

The answer is: yes and no! The question raises complex issues that cannot be easily answered in a short space. So let me take a long space. (And if you are interested, read on, read slowly, and re-read if you need!)

There are a couple of complicating factors. The first is how we use the English word, ‘hell’ to translate various Hebrew and Greek words. The second is the history and meaning of the phrase in the Apostles’ Creed, “he descended into hell”. Let me now try and unpack these issues in turn.

There are a couple of complicating factors. The first is how we use the English word, ‘hell’ to translate various Hebrew and Greek words. The second is the history and meaning of the phrase in the Apostles’ Creed, “he descended into hell”. Let me now try and unpack these issues in turn.

The various uses of ‘hell’ in translating the Bible into English

The English word ‘hell’ often does double duty in translating words from the original biblical languages of Hebrew and Greek.

The Hebrew word ‘Sheol’ is pretty much a close equivalent of the Greek word, ‘Hades’. These words (especially ‘Sheol’) can refer simply to the grave, where bodies decay. But more particularly they can also refer to what I define as “the shadowy place dead souls go to await their punishment” (i.e. before the final day of judgment).

To give you an idea of the range of meaning, in the New Testament, for example, Hades is translated by the NIV variously as:

•“the depths” (Matt 11:23)

•“hell” (probably here the final place of punishment, Luke 16:23)

•the “grave” (Acts 2:27, 31).

It is also simply transliterated as ‘Hades’—something like the dominion of the dead (Matt 16:18; Rev 20:13).

But there is another Greek word, ‘gehenna’, also translated by our English word, ‘hell’, found most often on the lips of Jesus in the Gospels. This word refers to the final place of eternal punishment for those who die unrepentant and unreconciled to God (e.g. Mark 9:43, 45, 47; Luke 12:5).

So when we see ‘hell’ in our English Bibles, it can mean ‘the grave’, or the ‘place dead people go’ (before final punishment, i.e. Sheol/Hades), or it can refer to the ‘place of final punishment’, i.e. ‘Gehenna’ (or ‘Hades’ once in Luke 16:23).

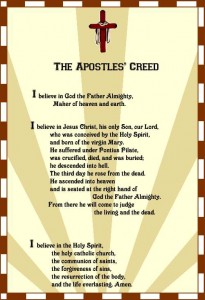

The “descent into hell” in the Apostles’ Creed

This confusion and even ambiguity becomes a problem when we consider the use of the phrase “he descended into hell” in the Apostles’ Creed and historical theology.

The text of the Nicene Creed seems to have been discussed, agreed and then developed over several well-known and official early church councils (Nicea, Constantinople and Chalcedon).

By comparison, the Apostles’ Creed was not written or agreed at any one church council, but evolved much more organically from about 200 AD to 750 AD. Along the way, the manuscript record shows it existed in various different forms.

It may surprise you to know that the phrase “he descended into hell” has not been found in any of the earliest versions of the Creed, until it appears in one of the two versions cited by Rufinus (390 AD). Then it disappears and does not seem to occur again until 650 AD. And even when Rufinus mentioned it, he took it to mean that Jesus descended to the ‘grave’ (i.e. the Greek form of the Creed used ‘Hades’—the place dead bodies go—as opposed to ‘Genenna’, the place of eternal punishment).1

A good guess about what happened is that “he descended into Hades” originally appeared as an alternate way of saying “he was… dead and buried”, as the Creed now says in the line before. But then someone thought they’d keep both phrases from the separate versions, and since “descended into hell” was listed after “dead and buried”, it was taken as something happening later in the chronology.

The verses (in my view) that could most likely support a physical descent into the realm of the underworld come from 1 Peter 3:18-20 (and 1 Peter 4:6). I don’t have time and space to go into all the details. But in brief, the grammar of these verses, and other theological concerns, seem to support the idea that the Spirit of the pre-incarnate Christ preached to those who lived in Old Testament times (especially in Noah’s Day, in this context) through the mouths of the prophets back then, and their spirits or souls (those who disobeyed the message preached, like people did in Noah’s Day) are now “in prison”. That is, these verses are not about Jesus going to the ‘underworld’ to preach judgment (let alone a second chance) to dead souls being held there.

I think that when Jesus died, his body went to the grave, and his soul went to be with the Father, until his body was resurrected on the third day. After all, on the day he died, Jesus promised the repentant thief on the cross that “Today you will be with me in paradise” (Luke 23:43), and his cry from the cross “It is finished” (John 19:30) implies his work of sin-bearing suffering had been completed on the cross and required no further trip to hell.

Conclusion

Calvin and others have provided a theological interpretation of the words “he descended into hell”: that on the cross, as Jesus was dying, he experienced ‘hell’ when he experienced a sense of abandonment from the Father as he bore our sin and faced the wrath it deserved.

I think this is a good theological account of the words, but is unlikely to be what the original authors of the line in the Creed meant.

A Postscript about the Creed

So we are left with a few options for the phrase in the Creed.

1. Drop the phrase altogether. But if we drop it from the Creed, that sounds like we are getting rid of our belief in hell. An unintended outcome, but it could be misunderstood that way by the casual observer.

2. Pick an alternative (as the recent Sydney Diocese prayer book, Sunday Services, permitted), namely either:

•(a) “On the cross, he descended into hell” (the theological interpretation), or

•(b) “He was crucified, dead and buried, he descended to the grave/place of the dead” (historically more accurate, but clumsy and repetitive).

3. Keep it as is (and try and explain the confusion).

After reading this, I am sure you will agree it is not a simple matter. But Christians are not very good on agreeing about change.

1. My source for this is Wayne Grudem’s Systematic Theology, Inter-Varsity Press, Leicester, 2000, p. 586.